Does school matter? Most anyone’s response would be, unequivocally, yes.

And yet startling results from a recent research study[1] suggest that, depending on the ability of the student, the answer may not be quite so clear-cut.

Researchers Betsy McCoach, professor in the Neag School of Education at the University of Connecticut, and Neag School alum Karen Rambo-Hernandez ’11 Ph.D., now assistant professor at West Virginia University, set out to examine the extent to which school impacts students’ levels of reading achievement over time.

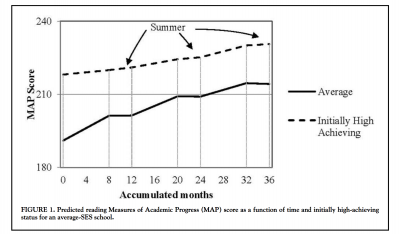

With access to national data for a population of more than 170,000 students from 2,000 schools, McCoach and Rambo-Hernandez compared students whose reading test scores at the start of third grade ranked in the top 2 percent – a group designated as “initially high-achieving students” – with those students whose reading test scores at the start of third grade were among the average.

Using test-score data that followed these two groups over three-and-a-half years – from the start of third grade to the start of sixth grade – the researchers were able to track the progress of each group over time in the subject of reading. These data sets allowed them not only to see how kids grew in reading during each subsequent school year, but also how their level of reading achievement was affected over each summer. That way, they could understand the impact, if any, of “summer slide” – the widely accepted notion that many schoolchildren tend to regress in some subject areas over the summer break.

“If [the high achievers] had not been in school, they would have achieved the same rate of growth in reading.”

—Karen Rambo-Hernandez ’11 Ph.D.,

Neag School alum and co-author of study

“Knowing how students grow over the summer allows researchers to understand more directly how time in school is changing the academic growth trajectories of students,” Rambo-Hernandez and McCoach state in the study, published in The Journal of Educational Research.

With this information, Rambo-Hernandez says, “We could compare what was happening during summer with what was happening during the school year, and look at those growth rates.”

12 Months of Summer Vacation > School?

Given that the initially high-achieving students were starting out ahead of the average-achieving students when it came to reading ability, the expectation was that they were likely to demonstrate comparatively slower growth in reading during the school year than the average achievers, who would presumably have more room for improvement. The researchers also hypothesized that high-achieving students would demonstrate greater growth in reading over each summer as compared with their average-achieving peers, who had started off at lower achievement levels in the subject.

According to the results, the average-achieving students’ reading growth did experience a boost during the school year and then stagnation over each summer break. School, as may be expected, seemed to enhance the reading achievement of the average students over time.

High-achieving students, meanwhile, though they continued to outperform average students, did in fact grow more slowly in reading than their average-achieving peers during the school year – as the researchers had anticipated. However, the high-achievers went on to maintain that same slow rate of progress in reading over the course of each summer, too.

In other words, “if [the high achievers] had not been in school, they would have achieved the same rate of growth in reading,” Rambo-Hernandez says – the implication being, as the study states, that “12 months of summer vacation would be as effective as attending school for these students, at least in terms of reading achievement.”

So while the above-average students did not experience so-called “summer slide,” they appeared to “grow at the same rate whether they were in school or not,” McCoach says.

Partnering With Teachers

If, as the findings suggest, attending school for most of the year has virtually no impact on reading achievement for high-achieving students, what can parents be expected to do?

“To me, the takeaway is you have to advocate for your kids, and you have to really know what is going on in the classroom,” McCoach says. “You have to try to ensure that they are getting appropriate instruction.”

She acknowledges that this may not always be easy, but recommends that parents approach this as a partnership with the teacher. “Every kid has a right to learn something new in school every day. I think when you frame it that way, maybe teachers and school administrators will listen,” she says. “It’s not about: ‘Look at how great my kid is; you need to do more.’ It’s about: ‘My child already knows what you’re about to teach. What can we do about that?’”

The issue, however, extends even beyond ensuring greater achievement in reading, according to Rambo-Hernandez, who previously served as a schoolteacher for 10 years. “We are doing a disservice if we put these students in classrooms and we are OK with not challenging them,” she says. “When they run into difficulties, I want them to know how to overcome them. If they’re not running into those difficulties, they’re not developing that skill set of grit, resilience, and persistence in difficulty. We need to make sure that they are getting an education that encourages them to tackle difficult problems.”

Going forward, McCoach says the study’s findings raise additional questions that could warrant further investigation.

“The big question that isn’t answered by this study is: Why? Why is it that these [high-achieving students] are growing at the same rate in the school year and in the summer?” she says. “The next step would be trying to find out: What is happening in schools, and what is happening during the summer? Are some schools better at serving high-ability students? And what are they doing? That, I think, would be really helpful.”

The full research study is accessible online here.

[1] Rambo-Hernandez, K. E., & McCoach, D. B. (2015). High-Achieving and Average Students’ Reading Growth: Contrasting School and Summer Trajectories. The Journal of Educational Research, 108:2, 112-129.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

LinkedIn

LinkedIn