Editor’s Note: This piece was originally published on UConn Today.

Devin Kearns began his career as a general education elementary school teacher for third-graders in Los Angeles, where he noticed many students had difficulty reading. The observation would lead to a dramatic shift in the trajectory of his work.

“After a couple years of really struggling to teach kids to read and working really hard and seeing kids not be successful, I decided there are a lot of things I must not be understanding about how to teach reading, so I started learning a lot more about that,” Kearns says.

Kearns first looked at reading strategies based in phonics, sounding out words and letter chunks. After seeing the dramatic progress students in a clinic for children with dyslexia were making using this approach, Kearns implemented the strategy in his own classroom, where he experienced the same kind of positive results.

“That made me really passionate about helping other educators provide high-quality beginning reading instruction to prevent dyslexia in kids or to help kids who are identified with dyslexia and other reading disabilities,” Kearns says.

“Professor Kearns’ ongoing work in the areas of special education and reading intervention, coupled with technologies like brain imaging, offers a fresh perspective into strategies that can ultimately help our schools successfully serve the needs of all students going forward.”

— Dean Gladis Kersaint

Kearns eventually moved from teaching in an elementary school to researching reading intervention at Vanderbilt University, where he earned his doctorate in special education. Now, as an associate professor of educational psychology in UConn’s Neag School of Education, he is taking his research into broader horizons and finding new applications for it.

‘What’s Going to Work Best With Kids’

Through a UConn Academic Plan grant, Kearns recently collaborated with Michael Coyne, professor of education, Jay Rueckl, associate professor of psychological sciences, and Ken Pugh, professor of psychological sciences, to determine the outcomes for two different educational strategies.

They tested a quick strategy against a longer, rule-driven approach to help children with difficulty reading.

Overall, the simpler strategy worked better than the rule-based one, they found. The more efficient approach consisted of asking kids to read syllables and then use them to sound out real and nonsense words. The rule-based strategy had children learn a rule about how to pronounce a certain set of letters and practice that rule many times.

After determining that the quicker strategy was more effective, Kearns and his team went on to investigate if it was more effective to study letter sounds or morphemes — units of meaning that make up a word.

Kearns was surprised that the morpheme strategy proved to be especially effective. “When I first left grad school, I didn’t really know much about morphemes,” Kearns says. “But, the data were clear: morphemes are important. So, I thought ‘I’m going to have to change direction,’ which is something in science that is very hard to do.

“It was like ‘OK, my theory didn’t pan out … but I’m just going to make the change because that’s what’s going to work best with kids.”

Some of Kearns’ other projects involve the classroom more directly. In a study that recently concluded, Kearns and Jade Wexler, associate professor of special education at the University of Maryland, worked with general and special education teachers in middle schools to find ways to co-teach more effectively.

“We want to make sure students with disabilities experience the same thing as other kids, but the data doesn’t show that it really works,” Kearns says. “Typically, there’s not much structure, and the special ed teacher ends up being more like a paraprofessional without a valuable role in the classroom.”

Kearns’ and Wexler’s program, which was implemented in 11 Connecticut classrooms, was successful. “The fact that we actually had better results in those classes is pretty remarkable and pretty exciting,” Kearns says.

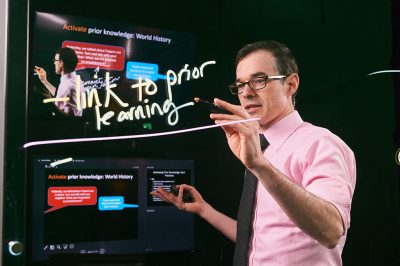

Kearns is also creating a series of videos on explicit instruction, a way of teaching students learning disabilities using a highly structured format. He uses explicit instruction techniques in his research on reading intervention and has seen its effectiveness firsthand. Kearns and several of his colleagues have been creating free instructional videos in UConn’s Lightboard room as well as free workbooks for the National Center for Intensive Intervention’s website.

Understanding Reading From Inside the Brain

Recently, Kearns also began incorporating neuroimaging into his research to see what the change in the brain looks like when kids use different strategies. One project he is working on with Roeland Hancock, associate director of the Brain Imaging Research Center, involves transcranial direct current stimulation. This kind of treatment involves transmitting a very small electrical current to the brain while someone is participating in a traditional reading intervention.

Some studies have already shown that people read better if various parts of their brain are stimulated. However, there have been limited studies so far about the effectiveness of this treatment for reading in English. Kearns’ project hopes to help bridge this gap. The study will involve adults reading while their brains are stimulated in different areas related to reading skills like visual recognition or phonics.

While he is far from working to implement this kind of intervention in schools, this research provides valuable information about whether this stimulation helps and if so, which parts of the brain should be stimulated.

Gladis Kersaint, dean of the Neag School of Education, says that making research connections across disciplines is critical to advance learning.

“Professor Kearns’ ongoing work in the areas of special education and reading intervention, coupled with technologies like brain imaging, offers a fresh perspective into strategies that can ultimately help our schools successfully serve the needs of all students going forward,” Kersaint says.

Looking forward, Kearns expects his research to continue to utilize new technologies in dynamic ways. Artificial intelligence programs, he says, could help determine the best text to add to a child’s reading list or to listen to them read and analyze which sounds or syllable combinations are giving them the most trouble.

Kearns hopes to continue to work to understand cognition as it relates to reading and exploring and improving reading interventions for struggling young readers.

“All of these things I’ve done and will continue to do have the potential to make a difference in kids’ reading by giving them the most efficient, effective instruction we can possibly provide,” he says.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

LinkedIn

LinkedIn