Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in CT Mirror. Bruce Baker is from Rutgers University; Robert Cotto is a Neag School doctoral student in educational leadership and faculty member at Trinity College; and Preston Green serves as the John and Maria Neag Professor of Urban Education at the Neag School.

The COVID pandemic has laid bare the extent of inequalities across Connecticut’s cities, towns, and school districts and the children and families they serve. Connecticut has long been one of our nation’s most racially and economically segregated states, while also one of the wealthiest. In the past decade, those inequities have worsened along both economic and racial lines. In 2021, Connecticut continues to face the interrelated challenges of segregation and school funding equity and adequacy. Connecticut must do better.

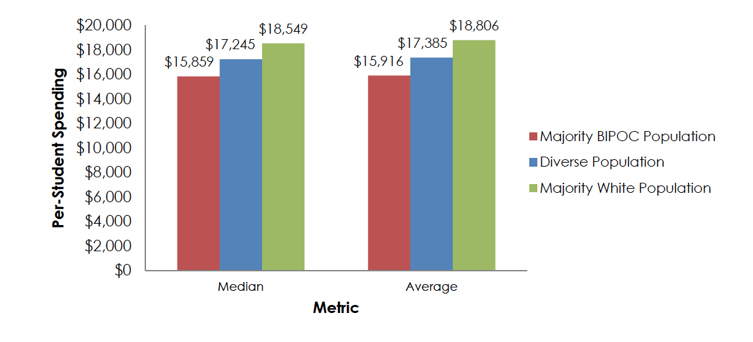

In two recent articles, we showed that Connecticut school funding continues to systematically disadvantage students in schools and districts serving predominantly Latinx communities. This finding is not new, with districts like Bridgeport, Waterbury, and New Britain recognized in numerous national reports as being among the most financially disadvantaged school districts in the nation. For a period, Connecticut appeared to do somewhat better on behalf of predominantly Black school districts, but this was largely a function of additional aid directed specifically at magnet school programs in Hartford and New Haven, and not by the design of the general aid formula. In a forthcoming article, we find that Black-white disparities in state and local revenues and in property taxation are among the largest in the nation and have worsened in recent years.

State school finance systems require constant evaluation and recalibration. Connecticut schoolchildren have waited far too long, especially those in the state’s low income black and Latinx communities.

Inequities in property taxation, fueled by a long history of exclusionary zoning and racial discrimination, are major contributors to the state’s school finance problem, and cannot be ignored. Municipal fiscal dependence is also a problem. Having a system in which local public schools rely on city and town budgets, where those budgets are based on prior taxing and spending behavior rather than current needs exacerbates the unevenness of school funding, hitting especially hard, schools in cities like Bridgeport. Above all, however, the state’s general aid program for schools – The Education Cost Sharing Formula (ECS) – falls short of addressing these inequities, and has never been calibrated appropriately to meet the needs of all of the state’s children.

Yes, longer-term structural changes to the property tax system, housing, and school segregation must be on the table. But more immediate steps are in order, to reform the state’s Education Cost Sharing Formula. The primary objective of a state school finance system is to ensure that regardless of where a child in the state lives or attends school, that child should have equal opportunity to succeed in school and life. Whether that system relies exclusively on local public school districts, or includes alternatives such as charter schools among the delivery mechanism to achieve these goals, choice is not a substitute for equitable and adequate funding. Equitable and adequate funding is a prerequisite condition, and necessary for closing the state’s racial and economic achievement gaps.

State school finance systems must accomplish two goals simultaneously:

- Accounting for the differences in needs and costs across districts, cities, and towns associated with providing equal educational opportunity;

- Accounting for the differences in local capacity to generate revenues toward the provision of equal educational opportunity.

Just like the name of the current formula – Education Cost Sharing Formula – suggests, the goal is to identify the “costs” of educating children from one school and district to the next, and then determine how to “share” those costs between local communities and the state. ECS is the primary mechanism by which the state shares the cost of educating children in Connecticut’s public schools. But ECS has never been based on any actual analysis of those costs or how those costs vary from one location to the next and one child to the next.

To clarify, “cost” per se, is what is outlined under the first point above – the “costs” of achieving specific outcome goals. Any legitimate conception of “costs” necessarily involves consideration of outcomes. The state must decide what those goals are and how they should be measured. And the state should engage in an analysis of the costs of providing all of the state’s children with equal opportunity to achieve those outcomes. This is what we mean by “calibration.” Connecticut needs this information sooner rather than later to take steps toward reforming or replacing ECS.

A recent national analysis estimated the costs of achieving the modest goal of national average outcomes on reading and math assessments, a benchmark that Connecticut children generally exceed. Even against that low bar (per pupil cost of achieving national average outcomes), a handful of Connecticut districts fall behind. Specifically, Bridgeport, Waterbury, and New Britain have spending gaps exceeding $5,000 per pupil. Similar analyses have been conducted in recent years to advise state legislatures in Vermont, New Hampshire, and Kansas. Two things we know well from these analyses:

- It costs more to achieve higher and broader outcome goals

- It costs more to achieve these goals in some locations and for some children than others

There are significant additional costs of achieving common outcome goals in locations with concentrated child poverty, large shares of emerging bilingual students with added needs, etc. Connecticut’s Education “Cost” Sharing formula falls well short of addressing these “costs.”

It will undoubtedly require a substantial boost in total state aid to bring all districts to spending levels sufficient to achieve a robust set of outcomes. Achieving more will cost more, plain and simple. Again, Connecticut is a wealthy state that can afford, through higher taxes on its most affluent residents, to address these issues without fearing a mass exodus.

To summarize, we propose a three-step process toward reforming the state school finance system to mitigate the state’s persistent racial and economic disparities in school funding and student outcomes:

Step 1: Conduct rigorous analyses to answer the question: What is needed to achieve equal opportunity for all of the state’s children to achieve a sufficiently robust set of outcomes?

Step 2: Recalibrate ECS with a formula specifically designed to hit these cost targets through a combination of a) equitable local effort and b) sufficient state aid;

Step 3: Fund it! (Raise sufficient tax revenues to support the system.)

Keep it up! Revisit. Evaluate. Recalibrate.

No state school finance system remains adequate in perpetuity without checks and balances. Goals change as do other demands on local public schools. State school finance systems require constant evaluation and recalibration. The time is now to start these steps. Connecticut schoolchildren have waited far too long, especially those in the state’s low income black and Latinx communities.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

LinkedIn

LinkedIn