The upbeat chant of “We shall overcome” on August 28,1963 still echoes in Neag Professor Emeritus Stan Shaw’s ears. The anthem led him through a sea of people at the Washington Monument where he joined his students from Prince Edward County, VA for the “best school field trip ever.”

That day became the peak of a “life-changing” summer, recalled Shaw, a then 20-year old college student majoring in sociology and education at Queens College, City University of New York.

The early 1960s marked the era of the civil rights movements’ constant clashes with the prevailing discrimination against African Americans and massive resistance to integration. Shaw, born and raised in a white middle class family, showed his commitment to equality and skill as a change agent early in his college career. As the president of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) at its Queens College chapter, he organized the “Queens College Student-Help Project” that tutored over 1,000 black children throughout the city of New York.

Given the success of the tutorial program, he and his fellow Queens College students decided to bring their efforts to the South, where “black communities were in segregated and unequal school facilities, faced constant economic threats and daily humiliation,” recalled Shaw.

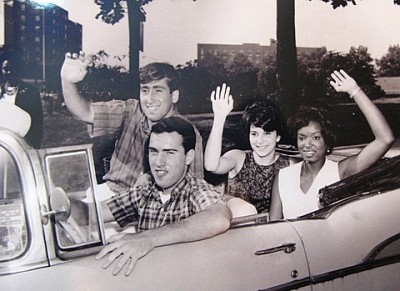

In the summer of 1963, Shaw and 16 other Queens College students, all white except for a single black student, embarked on a trip to Prince Edward County in Virginia, where all its public schools were closed for nearly four years with 1,700 black children kept out of the “private academies” created for white students.

The student tutors immediately felt the hostile climate from the white community, with their cars being followed in town and evening get-togethers surrounded by unfriendly locals. “We were told there wouldn’t be a problem as long as we stick to the teaching and stay away from the marches,” said Shaw.

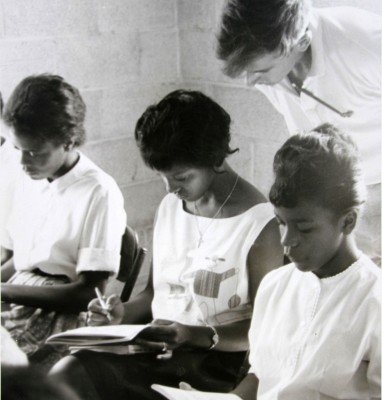

It turned out to be an unexpected challenge for Shaw and his peers, many of whom were new to teaching. It was especially difficult teaching kids in the same classroom who had missed different years of education. Yet, the group managed to attract more than 500 kids — across five churches — to the classrooms in churches throughout the county while club-carrying policemen were arresting demonstrators in the streets.

“I realized teaching punctuation and algebra is so much less important than giving these kids an idea of the need for education, also an enjoyment of learning,” Shaw wrote in his diaries recording the summer in Prince Edward County.

“If I could bring them to work better with groups of peers, to think and feel the problems and events facing their world, I would have done my job,” he reflected.

These goals were appropriate given that their last task in Prince Edward was to clean up and prepare the long abandoned classrooms to open as integrated public schools the following week.

Shaw’s six-week journey culminated in Washington D.C. where the Queens College tutors marched with a sea of people of all skin colors and listened to the “I Have a Dream” speech by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. “As we headed home, our vision of the world and plans for the rest of our lives had been forever altered,” recalled Shaw. “We learned that life was far more complicated than we had imagined, that we could make difficult choices and commitments, and live with the consequences of our decisions. We learned that we could confront danger and survive, but most importantly we could make a difference.”

In October 2009, 46 years after the Queens College Student-

Help Project, Shaw and other tutors returned to Prince Edward County to be honored by the Moton Museum, the once closed segregated R.R. Moton High School, and reunited with the black students they had guided through that deeply difficult time. “I thought I was only doing my small share, but I came to understand how much of an impact we had. We made a difference in their lives,” said Shaw.

Continuing his advocacy on civil rights and equality, Shaw has changed his battlefront to special education during his more than 40 years’ academic career at UConn, focusing on education for students with disabilities especially law and policy providing equal access for students with disabilities. Shaw remains as a senior research scholar at the Center on Postsecondary Education and Disability.

“I am proud of the efforts of white and black Americans who have successfully fought for change, but there is still much to be done,” said Shaw, looking back on the tremendous strides the country has made over the past 40 years since the summer of 1963.

“I would urge this generation of young people to pick up the mantle of social justice to continue the battle for equality for all including people of color, the LGBT community, immigrants and individuals with disabilities,” he said.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

LinkedIn

LinkedIn