Students across the state are wondering: what happened to Gillette Castle?

In the real world, the historic mansion built in 1914 by actor William Gillette sits safely atop its perch overlooking the Connecticut River in East Haddam. But in The Great Connecticut Caper – a serialized e-book being released, with help from UConn Libraries, by the nonprofit organization Connecticut Humanities – students must follow the clues to find and recover the national historic landmark.

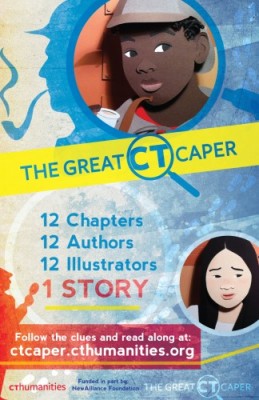

The mystery story, which incorporates Connecticut historical sites and figures, is being written by 12 Connecticut authors and illustrated by 12 Connecticut artists. It’s also being brought to life by faculty, staff, and students at the state’s public research university.

UConn Libraries’ Digital Scholarship and Data Curation team has been working for months with Middletown-based Connecticut Humanities to create the website for the book, as well as to develop interactive games to accompany it.

In addition, Neag School of Education associate professor Wendy Glenn and a group of Neag students are helping create a curriculum around the book for educators and parents.

Amanda Roy, the program officer at Connecticut Humanities who is spearheading the project, says she came up with the idea after seeing a presentation in Washington, D.C. about The Exquisite Corpse Adventure, a similar e-book published by the Library of Congress’ Center for the Book. Connecticut Humanities runs the Connecticut Center for the Book.

“How do we bring this back and make it uniquely Connecticut?” Roy recalls thinking.

After the results of an online poll dictated which Connecticut landmark would go missing in the book, the volunteer collective of authors and illustrators was let loose with a broad mission: write a story for children aged 8-12 in which Gillette Castle disappears, based only on what’s contained in the previous chapters.

Roy says that perhaps the most exciting thing about the project is the collaborations it has facilitated, including those between UConn and her organization.

Roy says that perhaps the most exciting thing about the project is the collaborations it has facilitated, including those between UConn and her organization.

“UConn Libraries have been a great team to brainstorm with. We started from scratch with this idea that didn’t have any meat to it, really,” she says. “It was nice that we could brainstorm and think about ways to get students and families to interact with each other and read this story.”

A springboard for learning

The website features games, puzzles, and other interactive components that teach readers more about the story and its setting, characters, and plot.

Roy, Glenn, and the Neag students are creating a curriculum to accompany each chapter, which includes activities, vocabulary words, and discussion questions to enrich the story.

For the UConn students, this project provides a different experience than the typical education coursework and internships, according to Glenn, an associate professor of English education.

“It’s a great opportunity for the students and me to work together in a different capacity, in more of a professional capacity than a teacher-student capacity,” she says.

Working on the curriculum with others will also prepare the students for the evolving landscape of the education world, Glenn adds.

“As schools are changing as institutions, more and more teachers are asked to work together, and I don’t know that teacher education programs do a great job of helping students develop those co-planning skills,” she says. “I think this will help them gain that knowledge.”

Kara Wojick ’14 (ED), ’15 MA recently started working with Roy on the curriculum as an intern. Wojick, who majored in secondary English education as an undergraduate, said the internship is a valuable supplement to her education.

She says the Connecticut Humanities job has given her an opportunity to continue the creative process of lesson planning for a variety of grade levels, and the activities she is coming up with are applicable to many different novels. The work is also exposing her to many state historical landmarks and nonprofit organizations she didn’t previously know about.

“These are resources I can, ideally, use in my own classroom next year,” Wojick says.

The lessons, with built-in connections to Common Core concepts, encourage exploration of everything from the types of literary devices used in the story to its Connecticut cultural references, Roy says. Those references also provide opportunities to involve other Connecticut organizations in the project.

For example, in the first chapter (online now), a tour guide on the Becky Thatcher riverboat discusses the Connecticut River Watershed. Not only does this give teachers a chance to teach students about watersheds, it has also enabled a partnership with the Connecticut River Watershed Council to promote their work.

The power of literature

The primary objective of The Great Connecticut Caper is two-fold, according to Roy.

“The main goal is to get kids excited about reading. But we also want to get them excited about their cultural heritage here in Connecticut, connecting them with their state,” she says. “We may have readers beyond the state, but for students in Connecticut – how great would it be for them to go with their family and friends to see this landmark they read about?”

Glenn, an expert in young adult literature, says the project exemplifies the power of books – regardless of the intended age group.

“[It’s] the recognition that literature has the power to help kids make connections across content areas and to find engagement in their community,” she says. “I think that transcends any audience.”

Chapter two of The Great Connecticut Caper, which is funded by the NewAlliance Foundation, will be released on Jan. 18 at ctcaper.cthumanities.org. New chapters come out every two weeks.

A launch party for parents and educators, featuring workshops with some of the e-book’s authors and illustrators, was held at the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History in New Haven on Jan. 28.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

LinkedIn

LinkedIn