Editor’s Note: The following piece was originally published on UConn Today.

Clewiston Challenger never intended to be a researcher. When he was young, Challenger wanted to be a police officer. As an undergraduate at the University of Connecticut, he originally majored in biology with the aim of becoming a scientist.

Challenger, an alum of UConn’s Neag School educational psychology and clinical psychology programs, ultimately decided he wanted to work as a coach and school counselor since he had benefitted from having great mentors in those roles.

While working in urban communities in Hartford and New York City, Challenger saw first-hand the inequality of those school systems and the inertia toward improving them.

“I learned a lot, that school systems are unequal and it’s not for lack of trying,” Challenger says. “It’s just that there are some systems in place that are inefficient and changing them takes more work and money than leaving them as they are.”

Since returning to school and earning his Ph.D., Challenger has dedicated his career to studying how to improve how students of color and student-athletes of color adjust to college life particularly at predominantly white institutions (PWIs) through teaching them strategies that start at the high school level.

“I recognized that my experience as a student and my race and my gender all came together in how I experienced my academics and my campus climate.”

— Clewiston Challenger,

assistant professor of counselor education

Finding Community

Students of color at PWIs often lack a sense of belonging, since the people around their campuses often do not look like them.

Challenger has found that many students don’t realize how important their racial or cultural identity is to them until they are in an environment that doesn’t reflect it.

“As an undergraduate, I wasn’t fully attached to my African American roots. And then I came to a predominantly white university and it kind of slapped me in the face like, ‘there are a lot more people who are not like me than who are,’” Challenger says. “That was a big piece for me, because you can’t run from that, so that begins to take a toll.”

At historically black colleges and universities or Hispanic-serving institutions, issues of racial and cultural identity are woven into the curriculum and campus atmosphere, whereas at most PWIs, those topics are regarded as something students should work out for themselves. But when some students realize their racial, cultural, and ethnic identities are significant to them but are suddenly not reflected in their world, it can manifest as mental health issues. These issues can lead to low academic motivation, school involvement and poor social interactions.

Challenger has found that this sense of identity and need for community are key factors to an individual’s success in college.

“When a person feels a sense of community and a sense of self, then they can make a better assessment of who they are, what they need and who they want to become,” Challenger says.

In the Spotlight

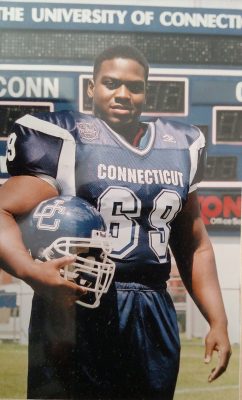

As a student and student-athlete on the UConn football team, Challenger became aware of the ways in which his identities impacted his experience.

“I recognized that my experience as a student and my race and my gender all came together in how I experienced my academics and my campus climate,” Challenger says. “So I thought it was kind of cool to see if other people felt the same way about their academic experience.”

Student-athletes of color can face unique challenges in college because they are on a much more public stage than the average student. Most of these athletes often feel pressure to not only represent their school and their athletic program, but their race and culture as well.

Being on this kind of stage increases pressure for students, which can cause or manifest mental health issues. The deeply ingrained stigma surrounding mental health as it pertains to student-athletes can be detrimental to their overall wellbeing and their academic and athletic performance.

Challenger has dedicated his career to studying how to improve how students of color and student-athletes of color adjust to college life, particularly at predominantly white institutions.

“It’s still taboo,” Challenger says. “Players are struggling with mental health issues on their own predominantly because athletes, male or female, are seen as warriors. They’re seen as Olympic-sized people, gladiators even. They’re not supposed to get sick or have issues with fear and adversity. And athletes take those external perceptions in deeply.”

Removing the stigma and having frequent, honest conversations about mental health can help student athletes access the resources they need before it becomes a crisis.

“The problem is the help usually comes when it’s at the most extreme,” Challenger says. “Now you’re taking extreme measures to save the person’s life or career when you’d rather catch the symptoms early. It’s like saying, ‘when my leg falls off then I’ll see a doctor.’”

Many schools with varsity sports have robust and comprehensive strength and conditioning, nutrition, and academic success programs. Mental health and wellness awareness and support should be part of that programming format as well, according to Challenger.

Building the Plane While Flying It

One factor Challenger looks at to determine how a student may adjust to college is their level of self-efficacy, the idea that they are able to accomplish goals and handle setbacks. If a student enters college with low self-efficacy, they will probably have a harder time making friends, getting involved and succeeding academically. Students with high self-efficacy will likely be more positively adjusted to college life.

One of the biggest pushes for Challenger’s work is to begin preparing students with the support they will need for college while they are still in high school. By determining a student’s level of self-efficacy, counselors in high school can work to maintain or increase their sense of self-efficacy before they get to college.

Challenger is currently launching a pilot program called the College Transition Program for Student Athletes (CTPSA) at a local high school as part of his research. The program will have eight sessions dealing with different topics student-athletes should understand before entering college, including navigating residential life, understanding the NCAA recruiting process and policies, acquiring financial literacy, choosing a major, and developing racial identity.

“Currently, when student-athletes enter college, they’re building the plane while flying it,” Challenger says. “Though student-athletes will go through tough adjustment times regardless, the goal of the CTPSA program is to maybe help them make better decisions or more informed decisions after being part of it.”

Challenger hopes to continue to develop this program into a “one-stop shop” for students where they can get help with test prep, mentoring, the admissions process and college tours.

Coming Back to UConn

When Challenger received his Ph.D. from Pennsylvania State University in 2017, he intended to work as a professor at an urban college and train future school counselors who wanted to work in urban schools. But when his former mentor — now a colleague — told him how UConn’s school counseling program had changed its model to focus on urban counseling and social justice, he applied for a faculty position.

“Students at UConn might need my experience more than students in Queens,” Challenger says. “I came back to UConn to be part of that that team, to be part of that vision, to be a part of that design, and that’s really inspired me.”

When counselors only have their own background to rely on, they often have a hard time working effectively with students and families of color. This can lead to frustration on both ends.

“That’s the reason why there’s a drain of good talent that doesn’t stay in urban education,” Challenger says. “New counselors often feel that urban schools are facing big problems. Many try to make an impact, and some are effective, some are not immediately effective, and many quickly give up or even leave the school if they feel ineffective working with urban students.”

For counselors and educators in urban communities to help students expand their horizons, they need to be trained to work with students of color who come from backgrounds different than their own, especially since schools everywhere are becoming more diverse.

“Students who attend typical school counseling programs that don’t harp on these multicultural issues and changes in school diversity are not adequately preparing school counselors for the reality they’ll face in the professional world,” Challenger says.

In addition to being well-trained counselors, Challenger encourages his students to be activists and advocates.

“Most times legislators make legislation about education without educators at the table,” Challenger says. “The counselors are often stuck enforcing regulations that don’t help or create academic achievement. We need school mental health professionals to represent the holistic component of students and families in the policymaking process.”

Putting it Together

In his research, Challenger believes we should treat students as whole people, rather than considering their academics, athletic performance, mental health, and social adjustment separately.

“I’m always surprised that people often do not make the connection. People don’t put it all together. They leave each aspect in isolation, addressing them separately, not intersectionally,” Challenger says. “And I think that’s either my skill, or that’s the way I think, is that they all do interconnect to address the person holistically.”

Challenger describes his role as a researcher as being similar to an entrepreneur. Research is not just about having great ideas, but having the tenacity and enterprise to get those ideas off the ground.

“That’s the toughest thing about research,” Challenger says. “You can have all the ideas in the world, but if you don’t have the funding, if you don’t have the motivation, if you don’t have the team, these are some challenges you can face in an effort to be effective. It’s a marathon more than a sprint.”

Follow UConn Research on Twitter and LinkedIn.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

LinkedIn

LinkedIn