Two members of the Neag School of Education faculty have been awarded two grants totaling more than $6 million in federal grants to expand their research into improving educational outcomes for students.

Sandra M. Chafouleas, Ph.D., a professor in the school psychology program and a research scientist at the Neag Center for Behavioral Research (CBER), has received a $2.3 million grant from the U.S. Department of Education’s Institute of Education Sciences (IES) for continuing work on Direct Behavior Rating (DBR), which she co-created with an earlier IES grant.

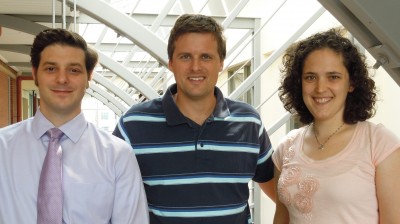

Michael D. Coyne, Ph.D., an associate professor of educational psychology and special education, program coordinator of Special Education, and also a CBER research scientist, was awarded a $4 million IES grant for his continued research into improving student language and literacy by providing a comprehensive system of Early Vocabulary Instruction and Intervention (EVI).

Chafouleas’s research team has focused on using DBR to measure respectful, non-disruptive and academically engaged behaviors that have been deemed important to the process of allowing all students to be in the classroom and ready to access instruction.

Although the tool has long been used for intervention and communication purposes, the DBR scales will continue to be studied in this new round of research as a method of assessing student behaviors. “This grant,” says Chafouleas, “allows for large-scale evaluation as to how DBR can be used to identify students at risk, and progress-monitor their response to behavior supports.”

The new research will take place in elementary and middle schools in Connecticut, New York and Missouri, and will involve approximately 2,000 students and teachers.

Chafouleas, who received her B.S. from the State University of New York at Binghamton, has an M.S. and Ph.D. in Psychology from Syracuse University, along with a Certificate of Advanced Study from SU’s Educational Leadership Program. In the new grant, she is part of a research team that includes Assistant Professor Megan Welsh and Professor Hariharan Swaminathan of the Neag School, as well as Associate Professor of Psychology T. Chris Riley-Tillman from the University of Missouri and Associate Professor Greg Fabiano of the University at Buffalo.

This grant is the largest the team has received to date in what has become a very competitive environment. Only five proposals at a time are accepted in this category, and Chafouleas’s was one of them. “What was extremely helpful to our team’s application,” she says, “was that it represented an extension of our original work, which is a priority for IES.” More information on DBR can be found at the team’s website, www.directbehaviorrating.org.

Coyne’s Early Vocabulary Intervention targets the “achievement gap” that persists among students in language and vocabulary development. “Our EVI team,” Coyne says, “is focused on the ‘vocabulary gap’ that is present at the beginning of kindergarten and continues to grow larger in the early grades. Early intervention can help at-risk students make meaningful gains in their vocabulary knowledge and, by extension, in their reading comprehension.”

To that end, Project EVI will work with more than 1,500 kindergarten students and teachers in Connecticut, Rhode Island and Oregon to implement high-quality classroom vocabulary instruction for all students as well as supplemental small-group intervention for those students most at risk. The intervention reinforces vocabulary introduced in whole-class activities by providing more explicit, scaffolded and interactive instruction coupled with immediate corrective feedback.

This multi-tiered approach is preventative rather than reactive. “Schools currently have access to very few evidence-based practices and strategies for targeting and narrowing the vocabulary gap,” Coyne says. “With this IES grant, we will be able to provide schools and teachers with the materials, resources and supports they need to maximize student outcomes.” The grant, the largest Coyne’s team has received, was one of only three awarded in this category.

Coyne, who received his B.A. in Music and Political Science from Williams College, has an M.T. in Special Education from the University of Virginia and a Ph.D. in Special Education, Literacy, from the University of Oregon.

IES is the research arm of the U.S. Department of Education with a budget of more than $200 million. Its aim is to improve educational outcomes for all students, especially those at risk of failure. The IES carries out its work through four Centers: the National Center for Education Research, the National Center for Education Statistics, the National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, and the National Center for Special Education Research, which awarded the grants to both Chafouleas and Coyne.

Heather K. McDonald has recently joined the

Heather K. McDonald has recently joined the