As an undergraduate at the University of Connecticut, Aaron Clark began pursuing a career in sports broadcasting, but quickly discovered that all the traveling and unpredictable hours were not aspects of a lifestyle he wanted. Instead, Clark switched gears, working toward a profession that afforded a reasonable and balanced schedule for athletics, family and work that makes a difference.

In his quest for a new career path, Clark emphasized his presentation and public speaking skills, alongside his passion for kids, and decided that becoming a teacher would best suit all that he was looking for.

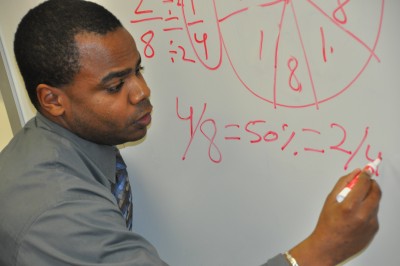

“I loved the idea of working with troubled youth,” says Clark, who has been employed at the Connecticut Juvenile Training School for young men for over three years now. “It was a challenge I knew I would enjoy and thought would be fun.”

Soon enough, Clark enrolled in the Neag School of Education’s rigorous five-year Integrated Bachelor’s/Master’s Teaching Education Program (IB/M), where he gained real world exposure to school system affairs and was engrossed by the professors’ level of expertise.

In particular, the lessons Clark took away from the required Positive Behavior Support and Interventions for Students (PBIS) with Disabilities course his junior year are some that have benefited him the most in his current role as a math teacher, working with a troubled population.

“It’s all about reward. They want to be given something. They’re dealmakers. A lot of them are there because they’re trying to do what they need to survive. Sometimes that meant making deals with people to get by,” says Clark. “PBIS is about rewarding positive behavior, which is something a lot of kids in my population get excited about.”

The PBIS approach is part of Neag’s Center for Behavioral Education (CBER), which was spearheaded in 2005 by Dr. George Sugai to research and teach in the areas of positive behavior support, behavior disorders, literacy, school psychology and special education.

Clark has come to understand that reinforcing positive behavior and academics boosts his students’ confidence, leading to higher success rates. By buying into what aids in good behavior, his students are more task-oriented, disciplined and inclined to focus on their schoolwork. Clark continues to learn, yet admits that this has been one of his biggest challenges so far.

Instilling the message that these youth do not have to revert back to whatever circumstance that originally put them in the facility is also key. Clark hopes that by relating to his students as much as he can, he will inspire them to discover a personal strength or skill they can use to better themselves after they serve their time.

“I struggled, too, but I knew what my goal was and worked hard to get that accomplished,” says Clark, who exemplifies how both persistence and determination pave the way toward success.

According to Clark, most of the youth he works with lack significant role models in their lives. They are desperate to talk about their lives, recapping sporting events and discussing their most recent art projects. Clark has tried to fill that need.

“[Teachers] need to be a guidance counselor, academic—not a friend, but a big brother/big sister at times,” says Clark. “You need to read your kids minute by minute, especially at my school. Anything can set them off. A lot lack any structure at home. They need some pushing toward what they’re going to do the rest of their lives.”

Although he currently is teaching algebra, geometry and intervention math, Clark hopes to soon teach his favorite subjects, social studies and history. Regardless, he is working with juvenile offenders and having a positive impact on them, just as he had hoped as a graduate student at UConn.

Clark also made a difference as a Neag School graduate student, exemplifying his leadership and dedication to creating change. In his graduate year, Clark took a lack of classroom diversity into his own hands and became a minority recruiting graduate assistant. This opportunity to create positive change within Neag was one of his fondest memories.

“I was the only male minority in all of Neag my senior year,” Clark recalled. “I’m glad to hear that the minority enrollment is a lot higher now.”

According to Academic Advisory Center Director Ann Traynor, Clark compiled information on prospective minority students interested in teaching and contacted students to answer any questions about the programs Neag offers, encouraging them to apply. He also reached out to Neag alumni to collect feedback on their experience in the IB/M and TCPCG (Teacher Certification Program for College Graduates) programs.

“This feedback helped us to improve our efforts to support, encourage and retain minority students in our teacher preparation programs,” says Trayor.

Although he may not have had the same classic teaching career path as many of his Neag counterparts, Clark has surely accomplished his original ambition of working with others in a challenging environment and has already seen great success.

“Aaron is a great young man with a strong moral compass and an engaging personality,” says former Neag School Dean Richard Schwab, Ph.D. “When he was a student at the Neag School, he was always someone who we could count on as an engaged and positive student leader. He is now a young alum who we will be reading a lot about in the future, as I see him building on his talents from his experience in this challenging classroom environment and becoming a key leader in school reform in our state.”

For more information about the IB/M Teacher Preparation Program, visit http://www.education.uconn.edu/howtoapply/ibm.cfm. To hear more, watch this video with Aaron talking about his experiences at the Neag School.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

LinkedIn

LinkedIn