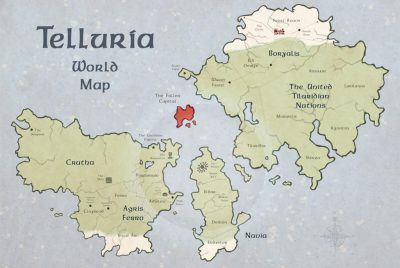

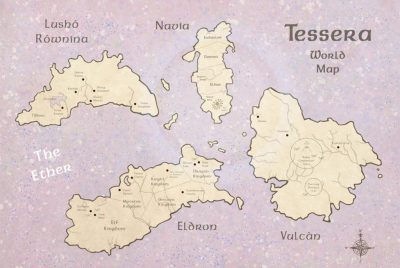

You are standing on the shores of the island Navía, peering out over the sea. From a distance you can see the two continents of Telluria: one is home to a powerful military empire, and the other blanketed by a vast desert. Suddenly, the continents disappear; Telluria is replaced by a world known as Tessera. Now you can spot the magical kingdoms of the southern continent Eldron, the lush plains of the eastern continent Lushó Równina, and the towering volcano of the western continent Vulcàn.

This is Polykosmia, a universe dreamed up by students in two classes led this spring by Stephen Slota (he/him, they/them), Neag School assistant professor-in-residence of educational technology. The students’ collaborative work, now completed, was compiled in an online wiki. Among other materials, the wiki includes interactive maps, a recorded timeline of this invented universe, subwikis for various regions, a text-based adventure game, and a short story. The project, an exercise in both worldbuilding and lesson planning, involved designing everything from mythologies to local governments to individual character arcs. Students also learned how to adapt worldbuilding activities into K–12 classrooms and how to design lesson plans that connected story objectives in a fictional world with learning objectives in the classroom.

The origins of Polykosmia

The idea for Polykosmia first came to Slota when three UConn MFA students enrolled in a pair of Spring 2020 courses, one an undergraduate digital media and design (DMD) class called Interactive Storytelling and the other a graduate-level educational psychology (EPSY) class called Instructional Media and Game Design.

Slota, who holds a joint appointment in the DMD department at the School of Fine Arts, saw the trio’s enrollment as an opportunity to play the two courses off of each other. Instead of assigning separate projects to either group, why not one larger collaborative storytelling project across both?

Slota’s DMD class was charged with designing the world Telluria, while the EPSY class designed the world Tessera. The task for the three students enrolled in both courses was to design a bridge between the two worlds: an island they called Navía, which would exist in both worlds simultaneously, tethering Telluria and Tessera together. This ‘bridge’ was kept a secret until the end of the course, when it was revealed to the rest of the students that the two worlds they had created were actually part of the same universe.

The three students “did a lot more co-storytelling with me as I navigated what the final product was going to look like,” says Slota. “I relied on them to help provide a framework for the other students to build around.”

Designing Polykosmia

To start the project, groups of students in each class were assigned distinct regions in their respective worlds. Each group had to assess the stability and strength of various societal systems in their region (government, economy, social relations, culture) using a process originally devised by Trent Hergenrader, associate professor of English at the Rochester Institute of Technology. Then, they had to think about how those systems could have originated and developed. For example: “How might a world have stable and highly effective race/gender/sexual orientation relations but problematic class relations?” or “How are the world’s governments empowered or constrained by various economies? How did these institutions come to be in the first place?”

Halfway through the semester, COVID–19’s global spread put a spotlight on societal institutions in the real world. Slota began noticing parallels.

Such questions would turn out to be prescient when, halfway through the semester, COVID–19’s global spread put a spotlight on societal institutions in the real world. Slota began noticing parallels, saying that quarantine made them “reconsider what our institutions do and why we have them,” which was exactly what students were doing with their regions in Polykosmia. Slota pointed to this as an example of how real-world societies respond to global issues. As they put it: “Look, this is how different levels of leadership react at different times, and these are the kinds of incentive structures they’re motivated by.”

After considering the societal institutions of their respective regions, students began designing cities, trade routes, histories, and character arcs. They also created stories of Polykosmia in the form of interactive games, graphic novels, and short stories.

When the work was completed, Slota revealed the secret that the two worlds each class was working on were actually connected. “It wasn’t until the very end of the course that everyone finally got to read the wiki and understand what was being hidden from them throughout the semester,” Slota says.

Devin Quinn (he/him) ’21 (SFA), a student in Slota’s DMD class, says he knew some sort of reveal was coming. “I was … counting down the days until the assignment was completed,” he says. “It really brought a grin to my face seeing all the cool work that people had done.”

Slota had a similar reaction to the final product. They said that reading some of the individual student work made Polykosmia feel especially real. “I felt like … I could actually continue to explore and there would be more to find and discover,” Slota says. “I don’t know that I’ve ever experienced such an emotionally powerful response to [a worldbuilding exercise] before.”

Worldbuilding in the classroom

In Slota’s EPSY class, the students — primarily members of the UConn Two Summers Educational Technology program — were tasked with implementing similar worldbuilding exercises in the local school classrooms where they serve as teachers.

Graduate student Megan McCarthy (she/her) decided to try worldbuilding in her kindergarten classroom. At first, she was apprehensive about how worldbuilding would work with students who were still learning the basics of reading and writing. Many of her UConn classmates are teachers at the middle or high school levels, and she wondered whether and how she could get kindergartners to grasp the idea of building a fictional storyworld.

“I don’t know that I’ve ever experienced such an emotionally powerful response to [a worldbuilding exercise] before.”

— Stephen Slota, assistant professor-in-residence

She decided to have her students collectively create a town, brainstorming what kinds of institutions they would want to include, almost, as Slota says, like Richard Scarry’s town in the popular children’s book Busy, Busy World. The students thought about what function these institutions provided and why they were important. McCarthy says her students reacted positively, giving her a change of heart about how implementable a worldbuilding-based lesson could be in an elementary school classroom.

Slota believes worldbuilding can be used as an essential tool in any classroom. With activities like these, Slota says, “you’re turning over control of student learning to the students themselves.” Students get to do their own exploring while the teacher guides them. It is a highly participatory activity where students “are actors in their own learning. They’re not just sitting passively, absorbing what they’re told.” Slota points out this is exactly what the Next Generation Science Standards emphasize: “the new set of science standards that are coming out are all based on inquiry.”

The key to creating an effective worldbuilding-based lesson, says Slota, is developing a one-to-one relationship between the story objectives in the world and the learning objectives in the classroom. For instance, students might be given a tabletop roleplaying game to play, but rather than a fantasy-style objective like ‘fight the troll,’ they would be asked to ‘construct a protein using an amino acid table,’ mirroring tasks that real-world professionals perform as part of their work. The goal is to put students in the same situation they would be in when they would actually apply the skills learned in the course (i.e., transfer of learning).

Impact of the project

For Slota, the Polykosmia project was an experiment — one that, once they saw the final product, they knew had been a success. They said they are eager to try it again and recommend that other faculty try projects similar to Polykosmia.

Part of Slota’s goal with the project was to supply students with a new understanding of lessons that are based in exploration. McCarthy says that the class changed her mindset as an educator, broadening her perspective on the kinds of lessons that could be applied in the classroom.

Slota doesn’t underestimate the potential impact of worldbuilding for the educational system. The project, Slota says, “made me confident that going forward, we’re going to be in a position where we have much better educational resources no matter where they come from.”

Explore the entirety of the fictional universe of Polykosmia online.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

LinkedIn

LinkedIn