Hartford Courant (Neag School alum William Collins featured)

Neag School 2017-18 By the Numbers Report (PDF)

L.A., Oakland Teachers Rally Amid Deadlocked Contract Talks

Capital & Main (Recent study co-authored by Preston Green referenced)

Dr. Alan Addley Named Connecticut’s 2019 Superintendent of the Year

CAPSS (Neag School alumnus Alan Addley was named Superintendent of the Year by the Connecticut Association of Public School Superintendents)

Cromwell Man, VP of Student Affairs at ECSU, Wins Latino Lifetime Achievement Award

The Middletown Press (Neag School alum Walter Diaz was recognized with a Lifetime Achievement Award from the CT Assoc. of Latinos in Higher Education)

Memes and GIFs as Powerful Classroom Tools

Faculty Focus (Ph.D. candidate Kristi Kaeppel co-writes this piece)

Increase in Minority Teachers Not Keeping Pace with Influx of Minority Students

CT Mirror (Joshua Hyman, who has a joint appointment with the Neag School, is quoted on his research about same-race teachers having big effect on black children)

Queen Rania Meets 2nd Graduating Cohort From Teacher Academy

The Jordan Times (Educational leadership program in Jordan created in partnership with UCAPP)

Advancing Human Rights Education in Connecticut 70 Years After UDHR

Seventy years ago this week, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in Paris. This milestone document, on Dec. 10, 1948, established a common standard of fundamental human rights for all peoples and nations in response to the atrocities committed during World War II, and sought to protect and safeguard those rights for future generations.

Seventy years ago this week, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in Paris. This milestone document, on Dec. 10, 1948, established a common standard of fundamental human rights for all peoples and nations in response to the atrocities committed during World War II, and sought to protect and safeguard those rights for future generations.

“All anniversaries provide a moment to reflect and take stock,” says Glenn Mitoma, an assistant professor of curriculum and instruction in the Neag School. “The UDHR was written in the aftermath of World War II, a catastrophic moment in history that has important lessons for us today. We can use this anniversary as an opportunity to reflect on and rededicate ourselves to the goal of a more just, equitable, and inclusive world.”

“The explosion of hateful rhetoric and associated acts of violence has demonstrated the U.S. needs to work on developing a culture of human rights.”

— Glenn Mitoma, Assistant Professor,

Human Rights and Education

Mitoma, who has a joint appointment with UConn’s Human Rights Institute, wrote his first book on the history of the UDHR, citing human rights education as a framework for pursuing justice and building a more equitable society. In conducting his research, Mitoma says he saw the importance of intertwining human rights and human rights education.

“The current political and social climate has made the necessity of human rights education clearer,” he says. “The explosion of hateful rhetoric and associated acts of violence has demonstrated the U.S. needs to work on developing a culture of human rights.”

Human Rights Education Efforts at UConn

Also serving as the director of the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center at UConn, Mitoma has been leading a wealth of ongoing initiatives focused on promoting human rights education throughout Connecticut’s K-12 public schools. While his efforts have reached students and teachers in schools across the state, preservice teachers studying in the Neag School, as well as the wider community, Mitoma says he believes UConn, the state of Connecticut, and the country as a whole can do more to expand their human rights initiatives.

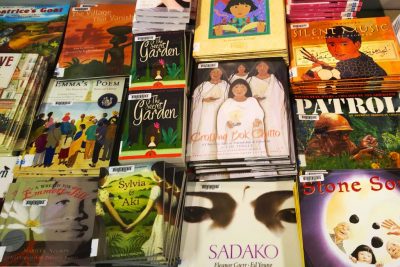

Most recently, the Dodd Center hosted the 2018 Children’s Literature and Human Rights Workshop this past month to provide free instruction for Connecticut educators on how to include human rights education in the classroom using children’s literature. Participants were introduced to the Dodd Center’s newly developed Human Rights Reading Tool, a tool educators can use to evaluate children’s books for teaching challenging human rights matters.

Additionally, workshop participants learned how to create space in their classrooms to teach human rights, how to defend their decision to bring up sensitive topics, and how best to teach related content for specific age groups. Teachers, Mitoma says, can occasionally face opposition from parents or even school administrators when introducing human rights issues in the classroom because such topics are frequently sensitive and may be viewed as being political, despite being valuable sources of learning.

“Human rights education allows kids to explore what their rights are, so that they’re aware of them and they can defend them in any circumstance, but they can also respect other children’s rights and the rights of other adults,” says Ellen Agnello, one of the workshop facilitators and currently a Neag School Ph.D. student studying reading education.

“When students understand what their rights are, they’re able to see where violations are, and so they’re more willing to act to make sure people’s rights are ensured,” adds fellow workshop facilitator Joan Weir, a Neag School Ph.D. student studying writing instruction for deaf/hard of hearing students.

Mitoma also coordinates Upstander Academy, another professional development opportunity that encourages education professionals to focus on human rights violations in order to address historical and current issues in the classroom. The six-day workshop provides time for participants to develop new skills for student engagement, learn how to foster a value-based classroom, and reflect on their personal and professional experiences.

In 2017, the Dodd Center inaugurated the Malka Penn Award for Human Rights in Children’s Literature, named in honor of Michele Palmer, an oral historian at UConn’s Center for Oral History and founder of the Malka Penn Collection of Children’s Books on Human Rights, which is housed at the Dodd Center. The annual award is presented to an author who explores human rights issues or themes through stories about individuals who navigate violations of their rights and make a difference in the lives of others and their own.

Veera Hiranandani was the 2018 recipient for her historical fiction work The Night Diary,which follows 12-year-old Nisha and her family’s treacherous journey to the new border of India during the 1947 Partition of India.

Mitoma has also led the coordination of the Dodd Center’s Exhibition of Human Rights in Children’s Literature, an art and children’s literature exhibit that highlights and conceptualizes themes from children’s books and the lasting effects they have on populations, in order to remind educators, parents, lawmakers, and other stakeholders of the importance of protecting children’s rights. Inspired by the U.N. Convention on the Rights of the Child, the exhibition focuses on core principles within the U.N. Declaration of the Rights of the Child, such as the right to education, food, health, participation, safety, and shelter.

The exhibit is featured at the Dodd Center and made possible through collaboration between the Northeast Children’s Literature Collection, UConn’s School of Fine Arts, and the Neag School.

Connecting Across Classrooms in Connecticut

Mitoma has helped bring human rights education directly into schools across the state as well, by introducing human rights education into the curriculum, including that of Manchester High School, one of the Neag School’s partner schools where aspiring teachers receive firsthand teaching experience.

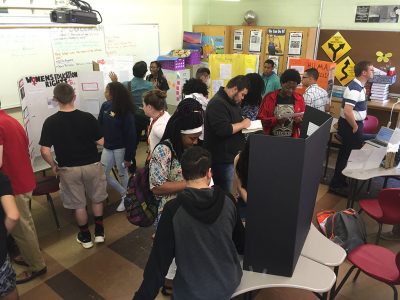

For the 2017-18 academic year, junior and senior students at Manchester High School were required to take human rights coursework to graduate. There are two levels of coursework — one is an Early College Experience (ECE) course in human rights, where students receive college credit and attend a youth summit, and the other is a college preparation course through which students receive high school credit in order to fulfill their graduation requirements.

“Having this class has exposed students to new lines of thinking, challenging their belief systems around certain issues and topics, and has been an inquiry-driven class,” says Neag School alum Jacob Skrzypiec ’13 (ED), ’14 MA, who teaches social studies as well as the ECE human rights course at Manchester High. “I’ve seen kids who have found their voice in trying to make the smallest of changes around them. Students are willing the engage their community in a different way.”

Skrzypeic also worked with Mitoma and Abigail Esposito ’14 (ED), ’15 MA, another Neag School alum and now a social studies teacher at Conard High School in West Hartford, to coordinate the annual Connecticut Human Rights Youth Action Summit. The summit provides high school students with the opportunity to explore human rights issues in their communities and around the world. It also allows them to build connections, collaborate, and network with their peers statewide.

“Having this class has exposed students to new lines of thinking, challenging their belief systems … I’ve seen kids who have found their voice in trying to make the smallest of changes around them.”

— Jacob Skrzypiec ’13 (ED), ’14 MA,

Teacher, Manchester High School

“There’s a number of schools in Connecticut working on human rights education, and we believed we needed to start working outside of schools and getting kids interested in collaborating and doing meaningful work together,” says Skrzypiec.

For the 2018-19 iteration, two summits were held in November — one at the UConn Storrs campus and the other at the Stamford campus. High school students from Manchester, West Hartford, Storrs, Darien, and Stamford explored the theme “Human Rights in our Backyard.”

“We wanted kids to focus on what are Connecticut-based and localized examples of human rights violations, rather than looking at them on a global scale,” says Skrzypeic. “We wanted to draw human rights down to the local level.”

Asmaller summit will be held in March for students to reconvene and share their projects’ challenges and successes, and learn skills they can directly apply to foster social change in their community.

‘A Responsibility and an Obligation’

Moving into the future, Mitoma says he would like to see UConn become a leader of Connecticut’s human rights initiatives and education, and to use its resources and prestige to promote positive change.

“UConn, as a university, and higher education in general, has a responsibility and obligation to use our influence as a prestigious and powerful institution to foster positive change in our communities. Our focus will continue to be on teaching and research, but we have an obligation to do more direct outreach and engagement. We need to work harder,” says Mitoma.

Mitoma says he hopes that going forward, UConn will become a model for other academic institutions and use its expertise to engage with the community around it to serve the public.

“We need remember that we are a public institution that serves the public, and work directly with communities on issues they have identified as critical,” says Mitoma. “Our efforts with schools, particularly those that would otherwise not have access to resources and expertise of the University, are aimed at building that culture of human rights from the ground up.”

Learn more about the 70th Anniversary Celebration of UDHR.

Related Stories:

Ducks Name Chelsea Gamble Head Coach

Go Ducks (Neag School alumna Chelsea Gamble was appointed head coach of Oregon’s lacrosse team)