GlobalEd 2 may sound like a game that leads to world domination, but it’s actually one that leads to word domination.

GlobalEd 2 may sound like a game that leads to world domination, but it’s actually one that leads to word domination.

Writing quality and self-efficacy scores of middle schoolers in many cases double after 14 weeks participating in the computerized, interdisciplinary, problem-based GlobalEd 2 social studies game, which requires classrooms represent assigned countries and—via monitored email, chat and other secure online interactions—work with other “countries” to find solutions for water supply, climate change and other real-world, contemporary science problems.

Pre- and post-game evaluations of students also show improved critical and scientific thinking, leadership, engagement and problem solving abilities. African-American students from schools located in urban, low-economic, areas tend to have the biggest increases, closing any academic gaps seen at the start of the game between them and their Caucasian, suburban counterparts.

But it’s perhaps the excitement for learning and individualized educational accomplishments that students write about in post-game evaluations that excite GlobalEd 2 coordinators the most.

“GlobalEd 2 takes technology that’s available in most middle schools and encourages students to use it to become decision makers, negotiators, persuasive writers and problem solvers, as well as to learn about different countries, governments and the very real human and science-related problems our world faces today,” said GlobalEd 2 co-developer Scott Brown, Ph.D., a professor of Educational Psychology at UConn’s Neag School of Education, who created the original version of the program with Mark Boyer, Ph.D., head of UConn’s Political Science Department.

“The best part: most of them want to do it,” Brown continued. “It’s fun—in many respects it’s like video gaming—and when you’re able to come up with a hard-to-find solution or negotiate a deal with another country, it’s exciting, too. For educators, it’s an empowering and innovative way to transfer knowledge, engage students in meaningful learning, and meet local, state and national demands for improved literacy, math and science skills.”

More than 5,000 public middle school students in 14 states, two foreign countries (Greece and Cyprus) and 35 Connecticut towns have participated in GlobalEd since its inception in 1998. Continuously funded by U.S. Department of Education grants and having evolved several times, the current program is being run as a partnership between UConn and the University of Illinois – Chicago, where Kimberly Lawless, Ph.D.—a graduate of the Neag School’s doctoral program in Educational Psychology: Cognition & Instruction—teaches and serves as UIC Educational Psychology department chair.

“It’s great to watch these kids working in the classroom, because what you see is kids excited about education. They’re noisy because they’re having meaty conversations or collaborating on the best way to get their point across,” said Lawless, who with Brown presented the success of GlobalEd 2 at the 2011 International Association for Development of the Information Society conference on Cognition and Exploratory Learning in the Digital Age in Rio De Janeiro, Brazil, and published a paper in the IADIS journal in 2011.

“The ability of the program to make such an impact on students in such a short amount of time is something I’m especially proud of, especially when you compare student improvements in high socioeconomic and low socioeconomic schools,” she added. “All of students improve significantly, but urban schools improved the most. Sure, they had more to gain, but we also feel GlobalEd engages students in a way that they haven’t experienced in the past. It’s not science with tests and beakers. It’s science in the real world.”

Any seventh- or eighth-grade social studies teacher willing to take part in the mandatory three days of paid, summer training can have their class participate in GlobalEd. The program runs once a year and is generally limited to 12-18 classrooms.

Phase 1 of GlobalEd consists of six to eight weeks of in-depth research before the actual “game” begins. Classrooms are assigned a country and, through the secure GlobalEd website, given writing tasks, questions and problems designed to educate students about their country’s geography, government, economics, culture, health challenges and human rights issues.

Students are then presented with a science crisis that affects all the countries and challenged to not just come up with a solution, but one that every country agrees to. The scenario is set six months into the future to minimize the impact of current news events.

Connecticut and Chicago seventh- and eighth-graders who participated last school year were tasked with coming up with global solutions to slow or reverse climate change and quickly shrinking water resources.

“Past scenarios have included stopping a flu pandemic and putting a stop to child labor, and next year we hope to focus on food production and finding alternative fuel resources,” Brown explained, “because they’re real challenges countries are facing right now and that very well at some point may affect the students participating.”

During Phase 2 of GlobalEd—the simulation or actual playing of the game—UConn doctoral students experienced in international relations monitor and track students’ exchanges, offering feedback and suggestions designed to encourage students to think critically, as well as consider the tone and tact of their communications with other countries. They also make sure students stay “in character,” use proper diplomatic language, stay respectful and present suggestions both doable and consistent with their country’s resources, culture and values.

To avoid the stereotyping, only students’ initials and country names are used in communications. Students are not told the name, gender, race or location of their competitors, which ensures “even ground,” Brown said.

“We know the stereotypes, and there are plenty of them—that girls aren’t really interested in science; that the white kids from the suburbs will do better at the game than the African-American kids from the inner city,” he continued. “But when you take all those social stereotypes that suppress a child’s ability to learn, or believe in him or herself, there’s nothing but possibilities and opportunities for learning. And that’s exciting.”

Although there are no official winners in the game, each classroom’s goal is to negotiate an agreement with at least one other country by the end of the eight-week simulation period.

Students in the countries that achieve that goal then have bragging rights during the two weeks of debriefing that make up Phase 3.

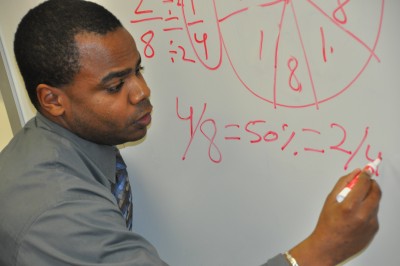

“Kids are competitive, and GlobalEd causes students to step up and give their all to find the best solutions to whatever scientific crisis they’ve been given,” said Rick Coppola, an eighth-grade teacher at John B. Drake Elementary School in Chicago, who’s participated in GlobalEd the past two years. “No kid wants to hear from the game monitor that they’re slacking. They want to hear that they are doing stellar, which is what turns out to be the case.

“Hands-on, applied learning is so much more interesting than watching me—or any teacher—stand up at a podium and lecture,” Coppola continued. “It’s dynamic, cooperative learning, and because the problems students need to solve are multi-faceted, there’s a job for everyone. Kids interested in research might focus on research; those who are very vocal may become the diplomats; and there are so many responsibilities and layers that it’s hard for anyone to slink into the background and let others do the work. It’s amazing how seriously kids take GlobalEd, pushing themselves and their friends to make the kind of evidenced-based arguments needed to successfully negotiate a deal.”

Brown and Lawless, who with Boyer and others are already planning for next year, feel strongly that the kind of real-world, tech-savvy, problem-based learning GlobalEd 2 provides is built on best practices and will soon become more widespread—or if not, should.

“GlobalEd changes the way teachers teach and students think,” Brown said. “Not every student who comes through the program will go on to become engineers or geneticists, but they will have the skills and abilities needed to be better problem solvers and decision makers, see the relationship between local and global issues, and to communicate their ideas more effectively. We also hope they have the realization that learning isn’t just confined to a classroom. It’s ongoing.”

The U.S. News & World Report released its rankings of Graduate Schools and the Neag School of Education continues to achieve top-ranking status as it rose in rankings to #32 in the nation. This ranking puts the Neag School as the #1 public graduate school of education in the Northeast and #22 among all public graduate schools of education in the nation.

The U.S. News & World Report released its rankings of Graduate Schools and the Neag School of Education continues to achieve top-ranking status as it rose in rankings to #32 in the nation. This ranking puts the Neag School as the #1 public graduate school of education in the Northeast and #22 among all public graduate schools of education in the nation. Museums provide students with opportunities and resources not available in the classroom. Through the physical participation of seeing, feeling, touching and overall experiencing the past, field trips to these sites and their corresponding lesson plans are crucial for successful learning in youth.

Museums provide students with opportunities and resources not available in the classroom. Through the physical participation of seeing, feeling, touching and overall experiencing the past, field trips to these sites and their corresponding lesson plans are crucial for successful learning in youth.

GlobalEd 2 may sound like a game that leads to world domination, but it’s actually one that leads to word domination.

GlobalEd 2 may sound like a game that leads to world domination, but it’s actually one that leads to word domination.

Paula R. Singer, president and CEO of the Laureate Global Products and Services Group, came back to campus recently to speak about online learning. She leads Laureate’s U.S. campus-based and online higher education business, serves as chair and CEO of Walden University, and oversees development and marketing of the company’s distance-learning offerings and partnerships around the world. Singer, who hadn’t been to campus in 30 years, earned a B.S. in education from the Neag School of Education, where she was the first education major to be selected for the prestigious University Scholar program. She spoke with the editor of Spotlight about teaching and online learning.

Paula R. Singer, president and CEO of the Laureate Global Products and Services Group, came back to campus recently to speak about online learning. She leads Laureate’s U.S. campus-based and online higher education business, serves as chair and CEO of Walden University, and oversees development and marketing of the company’s distance-learning offerings and partnerships around the world. Singer, who hadn’t been to campus in 30 years, earned a B.S. in education from the Neag School of Education, where she was the first education major to be selected for the prestigious University Scholar program. She spoke with the editor of Spotlight about teaching and online learning.