In our recurring 10 Questions series, the Neag School catches up with students, alumni, faculty, and others throughout the year to offer a glimpse into their Neag School experience and their current career, research, or community activities.

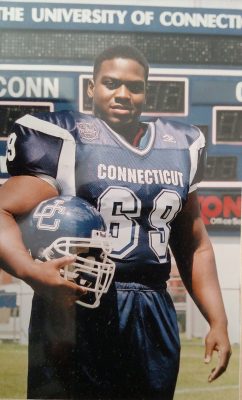

Clewiston D. Challenger joined the Neag School as an assistant professor of counseling last year. In 2003, Challenger earned his undergraduate degree in psychology and minor in criminal justice from UConn’s College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, and played football for UConn as a walk-on. He earned a master of arts in educational psychology from the Neag School’s counseling program in 2008, and a Ph.D. in counselor education and supervision from Pennsylvania State University in 2017.

Challenger’s research focuses on self-efficacy, academic motivation, and adjustment of students of color at predominately white institutions. He is a nationally certified counselor by the National Board of Certified Counselors, and has experience working as a school counselor in middle schools in New York City and Hartford, Conn., and at Penn State’s Morgan Academic Support Center for Student-Athletes.

What was your experience like as a student-athlete during your undergraduate career at the University of Connecticut, and how did it influence your graduate career and inspire you to pursue your current career? It was special to me in the sense that I had the ability to be in both worlds, both as a student and an athlete. I wasn’t recruited to play at UConn; I came as a walk-on, and that allowed me to have an experience at UConn that was pretty special because I was able to bridge both worlds. I always reflect on what got me to college, what got me to UConn, who helped me along the way, and who opened doors for me — and sports was one of them, school counselors were another, and so was the community I grew up in. I asked that same question of myself when I was a professional school counselor: If I were to go back to school, what would I go to grad school for? And I said school counseling, because I thought about all of the things that made me successful: School counselors always guided my way. I decided I wanted to train counselors to be good school counselors. I also wanted to train counselors to be good urban school counselors, particularly people who are not of color to be effective, multicultural counselors.

“I always reflect on what got me to college, what got me to UConn, who helped me along the way, and who opened doors for me — and sports was one of them, school counselors were another, and so was the community I grew up in.”

— Clewiston D. Challenger ’03 (CLAS), ’08 MA, assistant professsor

What made you want to come back and teach at UConn and the Neag School of Education? What makes these programs special, and what do you hope to contribute? UConn is a large university that is fully resourced. UConn has always led with technological advancements, has always led with campus development, and these things are important because you can be more effective in the work that you want to do when the institution is well resourced. When schools have more resources, they get more done. I recognized that I could get more done being at a place like UConn that has more resources.

What are your roles at UConn? I teach four classes in the counseling department at UConn. We’re a school counseling program that focuses on social justice, urban school counseling, and underrepresented populations in low-resourced schools.

What is it like being on the other end of the spectrum, teaching and conducting research at the institution where you started your career? It’s very much a shift because now I am literally looking in the looking glass, back at my own experience. When I was a student, I didn’t notice being a black male student-athlete, how that impacted my experience on campus. It’s odd now to be back at UConn as a faculty member because it’s come full circle. I came back to the college I went to, but I’m also a faculty member for the program that trained me, so it’s like coming back home to the place I first started on this journey and now I get to pay homage to that. At the same time, I’m also getting to pay it forward to the students I’m training, to the student-athletes I’m studying, and to the doctoral students that I’m able to influence. I really love and appreciate the role I have now, and also am very grateful and very proud of being a Husky.

What is the scope of your research? I research self-efficacy, how someone perceives their ability to do a task; academic resiliency, which is how students handle academic setbacks; and I look at university attachment and how all those factors influence academic motivation. If you’re well-adjusted to school, you have a higher chance of doing well. I also look at students of color, and particularly student-athletes of color who attend predominantly white institutions, like UConn and Penn State, because their experiences are different. They’re usually high-profile athletes brought in to play a sport and win games, but often the school climate and demographic makeup generally doesn’t look like the student, nor does it reflect their cultural or ethnic values. What I’ve found in my research is that those factors tends to impact their college experience, their adjustment to the school, and also impacts their academic performance.

You’ve worked at urban and suburban schools. What do you see as some of the biggest differences in school needs between rural, urban and suburban areas? The resource and social capital gap between urban and rural is actually closing, because those needs are becoming equally as high. Deep rural areas have high poverty rates and low-resourced schools as well. The same could be said for urban areas, where there are lower resources but are more densely populated. They’re fairly similar, but urban and rural are vastly different in culture, demographic makeup, and even family makeup. The one that stands out as most distinct is suburban because [those schools] typically have all the resources they need for students to be academically successful.

How did your experiences working at urban schools compare to working at suburban schools? I worked in New York City as a middle school counselor, where we had a club track team. Our students would literally run around the block [instead of at a track]. [But starting] the team — that little thing changed the attitudes of the students. The school really appreciated those kinds of gestures that teachers and educators were bringing in. I’ve worked at suburban schools where they already have the resources, so it wouldn’t be as appreciated if you started a track team; it kind of would just be expected.

From your perspective, how do the educational needs between boys differ from the needs of girls? How can educators meet different needs to create a positive impact on students? In my experience, boys have tangible learning experiences; basically, when they have to complete tasks for their learning, they tend to thrive. They’re able to exert that energy to the task and complete a project. To most boys, that really meshes with their personalities. The traditional educational model we have today works better for girls. That’s why teachers and counselors have to cater how they teach their classes and counsel boys and girls, because you have to differentiate the work in order to get comparable results.

Some of your research focuses on school engagement of boys in urban areas, and as a school counselor in New York City schools, you established intervention programs for at-risk students. What made you want to focus on boys in urban areas? I wanted to be able to create systemic change that wouldn’t just impact one school or one district. I wanted to create policy or academic work that would be effective across the U.S. or the world, and I knew I couldn’t do that from the office of one school. I wanted to know why students of color were struggling in schools, and were they able to do better. There’s a list of things that box people in, but I wanted to focus on education because you can unbox yourself if you know more. I decided I wanted to be in urban education because of the challenge. These schools and communities have the most need, and if anything, you see the most change in a short period of time from your interventions.

What do you try to instill in your students, and what do you hope they learn from you? I hope they learn to understand the different angles and perspectives of others, and the reason that’s important is that when you work with human beings in general, everyone has a different story. And, everyone’s looking at the same book differently. Students who desire to be school counselors have to realize that the students and families they serve are not all looking from their perspective, so the one thing I want to teach my students is their lens is not the most important lens. I encourage them to develop a kaleidoscope lens to view through and to learn to keep turning to see how things look differently from others’ perspectives. That’s important because salient to each of us as individuals are our own stories; we tend to put our backgrounds and our beliefs ahead of everything.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

LinkedIn

LinkedIn