In our recurring 10 Questions series, the Neag School catches up with students, alumni, faculty, and others throughout the year to offer a glimpse into their Neag School experience and their current career, research, or community activities.

Sandy Bell is an associate professor and program coordinator for the Neag School’s adult learning concentration in the Learning, Leadership, and Education Policy program. Bell also works as a consultant to support the development of agriculture extension education programs.

Bell received her bachelor’s in science and education from Colgate University in 1978, her master’s of physical therapy from Boston University in 1981, and her doctorate in adult and vocational education from the Neag School in 1994. She joined the Neag School’s educational leadership faculty in 2000 and was appointed as program coordinator of the adult learning program in 2006. Prior to this, she worked as a physical therapist for 15 years.

After nearly two decades at the Neag School, Bell will be retiring this month.

After about 18 years in the Neag School’s Department of Education Leadership, you are retiring. What are your plans? I have a 16-day trip to Italy planned, so I am making that my celebration and transition into retirement. On a long-term basis, my husband has been patiently waiting for me to join him in retirement, so we’re eager to move onto the next phase of our lives together. I am also continuing my consulting activities, particularly in the area of agriculture extension education. There’s still a lot to be done in that area, and I’ve been moving into consulting on grant-funded projects; that’s paved the way for me to continue more of that work on an independent basis.

What did you do prior to earning your Ph D. in adult learning, and how did you make the transition into your current role? I was a physical therapist for 15 years, and for the last five of those years, I worked with individuals who had work-related injuries. We started to work a lot with businesses and industries to help them figure out ways to prevent injuries, and I realized that a great deal of the success depended on the workers — as well as their employers — learning new techniques and safety strategies. I became fascinated with the learning aspect, both at an organizational level and individual worker level, so I thought I could benefit from a more structured way of learning about learning. I hadn’t thought about a change in my career when I started my doctorate, but doors opened for me to transition into academics once I completed my degree.

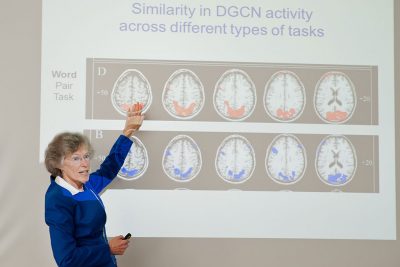

What is your favorite piece of advice that you have received during your career? I adopted something my mentor and advisor told me, which is that doing proceeds understanding. He encouraged me to embrace the idea that I did not have to ‘book learn’ everything and then apply it. He told me, “You can keep doing that, but you’ll never do.” The brain works in ways where reading and talking are only a fraction of what happens when you actually try the thing you’re learning about. A lot of times, I’ll see this in students — they gobble up and surround themselves with all the things other people have learned about a topic, yet they are hesitant to dip their foot into the pool or try to swim. With of my doctoral advisees, I say, ‘Just try it; dive in and start swimming.’ … which is more consistent with the way our brains work.

“For me, the question is not why lifelong learning is important — it will happen whether an individual thinks it is important or not. The question is: What do you do with your learning as you age? Can you share it to benefit others? Can you make positive changes with it? Can you use it to challenge your own beliefs and behaviors that may be keeping you from fully engaging in and enjoying life?”

— Associate Professor Sandy Bell

Why are you passionate about the field of adult learning? Adult learning plays a role in everything adults do, everything they are. The discipline focuses on the ways adults engage in learning, and not the education of adults, which connotes power differences between learners and educators. This distinction was very important for the founder of our adult learning program, Dr. Barry Sheckley, back in the early 1980s. The field has a broad reach. It thrives on the contributions of learners, practitioners, and scholars who have diverse backgrounds, knowledge, skills, and interests. It is important because no other discipline addresses how adults learn and how to best support their learning in all aspects of their lives.

Your research focuses on applying adult learning principles in the fields of agriculture extension education, conservation, and environmental protection. Where did that focus originate? In my very first grant-funded project, I collaborated with colleagues in our program and in the plant sciences department to help dairy farmers research projects on their farms. I realized early on that [the application of adult learning principles] was a big void in extension education and the field of agriculture education. … For me personally, it was extremely exciting and challenging academically. Being personally passionate about what you’re doing helps promote the research.

How can learning occur in adulthood in a way that changes perspectives or promotes more effective teaching and learning practices? Most people’s mindsets are based on the experiences they’ve had. Theoretically, one of the best ways to help people alter their mindset is to have them experience new things. The first step is for them to appreciate what their experience base is and realize that their reality is not the same as everyone else’s. I find that process has to happen before any technical information is shared. I think that’s where a lot of facilitators and educators miss opportunities to maximize learning. Often, they start by sharing conceptual information, so they’re just addressing that abstract, nonemotional part of people. It’s not until folks open up emotionally that they can fully learn.

You have worked with students across a range of ages. Do you see differences in how master’s degree students and older students approach learning? Some of the younger master’s students who have been in traditional academic settings since they were 4 years old may not have a lot of experience learning in ways that are not gradable, where they need to be responsible for their learning and set their own goals. Often, younger master’s students from science and technical fields don’t have experiences with learning activities focused on self-development compared to those in the humanities. I may work with them in ways that help them learn to self-regulate their own learning.

Whereas older students, particularly students pursuing doctorate degrees, are more independent, and usually have a lot of nonacademic life learning experiences that aren’t controlled by a teacher. They know what it’s like to fail and to pick themselves back up and figure out what went wrong. Those folks already have naturally developed learning self-regulation skills, so I can work with them in ways that are more advanced, which might help them appreciate some of their underlying habits or assumptions about their own learning.

What research are you most proud of? I worked with University of New Hampshire Cooperative Extension educators on a three-year professional development project funded by Northeast Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education [part of a larger, nationwide effort to invest in research and education that will advance American agriculture]. They gave me lots of latitude in helping their educators become more proficient in facilitating the type of learning they needed. It’s most rewarding for me because of the longevity of this work. The indicators of having an impact, and the ripple effect of it having evidence even years later where folks are still using the strategies and resources that we developed, is very rewarding.

How has your career shaped you as a lifelong learner — and what advice would you have for people to remain lifelong learners? I work in an atmosphere where I need to practice what I preach, and I try to look at things that I see as mistakes as opportunities for learning. I also need to be more patient with myself. I will extend this to other things that I don’t think I can do and will give them a try. I used to believe I couldn’t learn another language, but I’ve been taking an Italian course, and it’s been an eye-opener. I never appreciated how restrictive [that belief] was. I’m really glad that I’ve had that awakening, to see the power of a negative assumption about learning, and to challenge that assumption and learn things I never thought I could.

My advice would be to keep getting yourself into new situations where you are likely to be surprised. Our brains respond to novelty by making new neural connections. New and surprising things make us pay attention and question our assumptions. Over the past few decades, neuroscience researchers have accumulated lots of evidence showing that healthy aging adult brains have lots of capacity for plasticity — to make new neurons and neural connections. On the other hand, as we age, the ceiling in terms of brain capacity drops — we are less efficient in making new connections, and it gets harder to make new long-lasting memories. Lifelong learning is part of being human. The brain is wired to learn. Continued learning will keep that ceiling up as high as possible. For me, the question is not why lifelong learning is important — it will happen whether an individual thinks it is important or not. The question is: What do you do with your learning as you age? Can you share it to benefit others? Can you make positive changes with it? Can you use it to challenge your own beliefs and behaviors that may be keeping you from fully engaging in and enjoying life?

What will you miss most about working in academia? By far, the students. I feel lucky and privileged to have had the opportunity to work with them and to learn from them. I’ve learned about life from them. I’m amazed at some of the things that they’ve managed to deal with in their own lives, and I have a great deal of respect. Really some of the most important relationships in my life have been the ones I’ve developed with students.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

LinkedIn

LinkedIn