Boston Globe (George Sugai quoted)

‘What Matters Now’: Empower Teachers, Reorganize Schools for Success

Ed Prep Matters (NCTAF Commissioner Richard Schwab quoted regarding new national report)

Neag School Hosts Inaugural Teacher Leadership Academy in Storrs

This past July on the Storrs campus, 11 current teacher leaders representing 10 school districts from across the state spent five days engaged in a variety of learning activities during the inaugural Teacher Leadership Academy. The academy, hosted by the Neag School of Education from July 25-29, 2016, and co-directed by assistant professors Rachael Gabriel, Jennie Weiner, and Sarah Woulfin, was designed to enhance participants’ ability to support high-quality instruction, create conditions for reform, and lead change in Connecticut schools.

Participants were encouraged during the five-day program to share professional experiences and problems of practice, as well as collaborate to learn more about multiple aspects of teacher leadership and about how to engage as informal and formal leaders who can activate their voices for change. They also learned about the processes and difficulties of change and developed concrete skills to plan and communicate effectively with colleagues to help achieve growth and positive outcomes.

“I learned so much in such a short amount of time and really do feel empowered to make a difference as a teacher in my school,” says one participant. “I was encouraged and feel more confident in being able to make change in my school. I also know how to tackle a challenge in a positive way, and can speak to others in a problem-solving orientation.”

Partcipants also engaged in logic modeling in order to leave the academy with concrete plans on how they would exert their leadership and then measure their success. Each teacher leader created action plans for the upcoming school year on topics ranging from improving student discourse in math instruction and increasing coherence between middle and high school teachers to instituting a peer-coaching system to shift professional culture.

Among the academy’s featured guest presenters were Lissa Young, assistant professor of leadership and management at the U.S. Military Academy – West Point, who led a case study on climbing Mount Everest that raised several key concepts related to leadership, teamwork, and communication. Other guest speakers included a journalist from the CT Mirror and a troupe from nonprofit ImprovBoston, whose presentations focused on enhancing listening skills and confidence and bringing more fun into the workplace.

The academy also featured several faculty presenters from the Neag School, including John Settlage, who discussed data use in teams; Todd Campbell, discussing current conceptions of teacher leadership; Morgaen Donaldson, who talked about policy, and Marijke Kehrhahn, who focused on workplace learning and the conditions necessary for deeper forms of implementation.

Participants in the academy noted that these experiences, in concert, produced learning that they would take back to their sites and use in practice. One participant called the week an “amazing experience” and says “it’s hard to put into words all that I am taking away with me. This week was equal to a year of “professional development and then some.”

The program’s co-directors — Gabriel, Weiner, and Woulfin — plan to read and comment on the participants’ action plans and follow up with each of them in the coming months to celebrate progress, provide resources, and support further growth and development to help foster ongoing learning for this cohort of teacher leaders.

Learn more about the Teacher Leadership Academy at s.uconn.edu/NeagTLA, and check out photos from the program here.

Creativity, Marginalized Groups, and Empowerment

Alt view: The edGender Scope blog (James Kaufman’s research into creativity discussed)

The Fine Line Between Safe Space and Segregation

The Atlantic (Assistant professor Erik Hines quoted regarding UConn’s ScHOLA²RS House)

‘Country Prepped for Conversation on Education’

Editor’s Note: This story — written by Loretta Waldman — originally appeared on UConn Today, the University of Connecticut’s news website.

Last week, the National Commission on Teaching & America’s Future (NCTAF) released a report aimed at helping educators reorganize the nation’s education system in ways that support teaching, drive learning, and provide all students with the foundation needed to build a successful future. Building on a report the Commission issued 20 years ago, it addresses current challenges facing the nation’s educators and makes recommendations focused on improving teaching and learning in the U.S.

Professor Richard Schwab, former dean of the Neag School and now Raymond Neag Endowed Professor of Educational Leadership, helped shape the new report, “What Matters Now: A New Compact for Teaching and Learning.” He describes it as a call to collective action ultimately intended to ensure that all students have access to great teaching.

Q. What are the current challenges this report is intended to address?

A. Today, between a quarter and half of new teachers in the U.S. leave the field of teaching within their first four or five years on the job. This turnover incurs costs of more than $2 billion each year. At the same time, a mere five percent of high school students say they intend to pursue careers as educators, according to recent findings, and this is happening at a time when the achievement gap between high- and low-income students has been expanding over the past 25 years.

We have spent billions, passing endless pieces of reform legislation at the state and national level, yet still we have not succeeded in supporting or enhancing the teaching profession to the degree we must if we are to achieve the lofty goals all of us have for our nation’s schools.

Q. To what do you attribute this turnover?

A. My fellow commissioner, Jal Mehta, an associate professor at Harvard’s Graduate School of Education, summed it up well: For so long, we have asked teachers to do too much. The system is radically over-invested in student test scores as the only indicator of success and teacher evaluations as the primary lever of improvement. Those things are important, but it’s a matter of emphasis, and the result of this overemphasis has been a narrowing of curriculum and a lowering of teacher morale.

The bad press on education is giving teachers mixed messages and, in many cases, teachers are the victims. People don’t understand the challenges teachers face every day, and the lack of resources. And not every education program prepares teachers adequately. The report points out that most of the 66 million public school children in the U.S. are students of color. A quarter of those students live in poverty and more than half qualify for free and reduced lunch. More than four million of today’s students are not native English speakers, and more than six million have identified disabilities or special needs. Many more are undiagnosed. This diversity of students and their needs presents new opportunities and challenges for educators.

Q. The focus of your remarks was on teacher preparation, your area of expertise. The report calls for action around a new vision of teaching and learning. What part does teacher preparation play in achieving that vision?

A. I was there to talk about what it takes to do quality teacher education. I believe we’ve made great strides. At UConn, we have a five-year integrated bachelor’s and master’s degree program that provides a variety of professional experiences and puts our students in diverse settings, from Hartford and East Hartford to Mansfield. We have higher than average placement, and retention rates that are among the highest in the nation.

But here’s the rub for me: Teacher preparation has to be built in partnership with schools. If we are really going to do deeper learning and we are setting up these teachers and preparing them, we can’t then put them in schools that are not going to help them become the teachers we have worked so hard to prepare. You can mentor all you want, but if you are teaching well over 100 students in a day, and half of those kids are English language learners, how are you going to do deeper learning from 8 to 2 and still get in a 20-minute lunch? We have to somehow take a look at schools in this country. We have to look at both ends of the continuum.

Q. To help teachers stay in the profession and thrive, the report outlines a new compact that puts teachers at the heart of systemic change. Can you elaborate?

A. In this environment, we need to ensure that teachers have the time and opportunity to shift their methods from encouraging students to find the “right” answers to helping students “own” what they learn and apply it in their everyday lives. This new way of thinking about teaching and learning will drive a new system that asks much of teachers but gives them the supports they need to be successful throughout their careers. Essentially, the new system will establish a new compact between teachers, states, and districts; between teachers, students, parents; and the education system as a whole.

Q. How does this report build on the one 20 years ago?

A. The first one, “What Matters Most: Teaching for America’s Future,” changed the national discussion about what must be done to improve America’s schools so that all students experience success. The Commission drew attention to the overlooked fact that the most important variable affecting student achievement is the teacher. It made recommendations affecting every aspect of the teaching career, from recruitment and induction, to retention and recognition.

Since then, the traction created by that report has eroded. We have made great strides meeting the challenges, but then the political winds changed and the emphasis shifted. That’s why we felt the time was right, with all the talk of reform and when policy is shifting toward more engaging and relevant teaching and learning, to take a deep breath and look systemically at what we have to do.

I think our country is ready for a new conversation. If we could get 50 states to take a look, to breathe deeply for a year or two, and say let’s look comprehensively at what works and what doesn’t. To listen to all the voices and say okay, what do we know from research-based practice and what do we know teachers are doing every day.

We must move the focus from doing things to teachers that have no effect, or worse, make their jobs more difficult, to providing support that is research-based, consistent, and focused, and that fully engages teachers in designing the support they need and deserve.

Learn more here, or view the executive summary and full “What Matters Now” reports on the NCTAF website.

Neag School Faculty Awarded More Than $2M in IES Grants

Two Neag School faculty members in the Department of Educational Leadership have recently received funding — totaling more than $2 million — from the U.S. Department of Education’s Institute of Education Sciences (IES), as part of the latest round of grants issued by the National Center for Education Research (NCER)’s Education Research Grants Program.

Evaluation of School Principals

Morgaen Donaldson, associate professor of educational leadership and director of the Center for Education Policy Analysis (CEPA) at the Neag School, was awarded a three-year, $1.4 million grant for a project titled “District Policies Related to Principal Evaluation, Learning-Centered Leadership, and Student Achievement.” Donaldson’s co-principal investigators include assistant professor Shaun Dougherty of the Neag School, as well as Peter Youngs of the University of Virginia and Madeline Mavrogordato of Michigan State University.

“In the past five years, the great majority of states have approved legislation mandating that public school principals be evaluated annually using formulas that incorporate students’ academic growth,” state the researchers. “However, scant research examines how school district policies are related to leadership practices that are associated with improved student outcomes.”

The project aims to study 25 school districts in Connecticut, Michigan, and North Carolina, exploring associations between school district policies related to principal evaluation, principals’ enactment of learning-centered leadership practices, and student reading and mathematics achievement. This project was the only education leadership grant funded by NCER in the 2016 competition.

Examining Career Technical Education

Dougherty also was awarded a four-year, $695,000 grant for a project titled “The Causal Impact of Attending a Career-Technical High School on Student Achievement, High School Graduation, and College Enrollment.”

The research team — which includes Dougherty’s co-principal investigators and UConn colleagues Eric J. Brunner, associate professor of economics, and Stephen L. Ross, professor of economics — will focus on examining the impact of attending a CTE high school — in which all students who enroll participate in some form or career or technical educational training — on students’ achievement, high school graduation, and college enrollment. The project involves a partnership with the Connecticut State Department of Education and will use data from the Connecticut Technical High School System. Dougherty’s is one of eight recent NCER grants being led by early-career researchers.

Tom Healy Appointed Interim Principal for Central Middle School

Greenwich Post (Alum Tom Healy featured)

Encourage and Take Beautiful Risks

Editor’s Note: The following piece — authored by Ronald Beghetto, professor of educational psychology and an expert in creativity — originally appeared on the Corwin Press Corwin Connect blog.

What if we, as instructional leaders, supported creativity in teaching and learning? I mean really supported it. Here are a few things we might expect to see (and hear). We would see ourselves leading by example. We would view uncertainty as a sign that new thought and action is needed (rather than ignore it or try to quickly resolve it by force-fitting solutions). We would see ourselves engaging in possibility thinking. And hear a shift in our language moving away from “This is the way it is” and toward “How could or should it be different?” We would demonstrate a willingness to seek out diverse perspectives and honestly critique our ideas and beliefs (even our most cherished ones). We would also see ourselves stepping into uncertainty — taking measured action; failing fast, but learning even more quickly; and making small, but meaningful progress.

In short, we would see ourselves taking beautiful risks.

Beautiful risks bolster confidence, deepen understanding, and lead to new ways of thinking and acting. Taking beautiful risks has a cascading effect on others — encouraging them to take similar risks. As a result, we would see a growing recognition amongst teachers and students that creativity is not about “anything goes” or even “thinking outside the box,” but knowing when and how to strike a better balance between meeting curricular goals and, at the same time, providing students opportunities to develop and express their understanding of academic content in new and meaningful ways.

Creativity is not something that can be given or taken away. It is a capacity that all students, teachers, and instructional leaders always and already have available to them.

When we encourage and take beautiful risks, we would see teachers making slight changes to their existing curriculum to create more room for original student expression. We would see students taking intellectual risks in the form of seeking out new learning challenges, asking for assistance when needed, and being willing to make mistakes in an effort to learn more deeply. We would also see a movement away from learning academic content as a means to its own end and, instead, see academic content put to creative use. This, in turn, allows us to move away from underestimating what young people are capable of doing and toward providing opportunities for them to demonstrate the profound impact they can have on their own learning and lives.

When we encourage and take beautiful risks, we do so out of a recognition that learning and creative expression are complimentary (not contradictory) goals. We also recognize that beautiful risks do not require making radical changes or implementing yet another mandated reform initiative. Indeed, the last thing we want is a No Child Left Uncreative act.

Creativity is not something that can be given or taken away. It is a capacity that all students, teachers, and instructional leaders always and already have available to them. All that is needed is an opportunity and willingness to put it to use.

Put simply: If we really want to help teachers and students take the risks necessary to reclaim their creativity in schools and classrooms, then we need to start with ourselves.

Access the original blog post by Ronald Beghetto on the Corwin Press website. Beghetto is the author of the newly published book Big Wins, Small Steps: How to Lead for and with Creativity (Corwin Press, 2016).

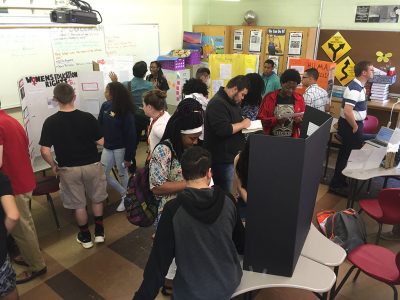

Early College Experience Program, Neag School Professor Expand Human Rights Education to High School Students

With 80 students currently majoring in the University’s human rights undergraduate program and another 40 to 50 enrolled as human rights minors, UConn stands out as one of just a handful of universities in the nation offering a degree program in the field of human rights.

But educating students in human rights issues need not be exclusive to college campuses, as Glenn Mitoma, assistant professor of human rights and curriculum and instruction, can attest.

Last fall, Mitoma piloted a launch of an introductory UConn course in human rights at three Connecticut high schools, in partnership with the University’s Early College Experience (ECE). UConn’s ECE program allows high schoolers across the state to take university-level courses taught by specially trained teachers at their school while earning credits that can be transferred toward a degree at UConn or other universities. The course is the only known concurrent enrollment course offered today in the field of human rights in the United States, Mitoma says.

“UConn has the leading human rights program in the country. We have this tremendous resource, and I am really looking to make the most of it for the secondary and primary education communities,” says Mitoma, who has joint appointments in the Neag School and UConn’s Human Rights Institute, while also serving as director of the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center. “My ambition is to make Connecticut a national model for human rights education.”

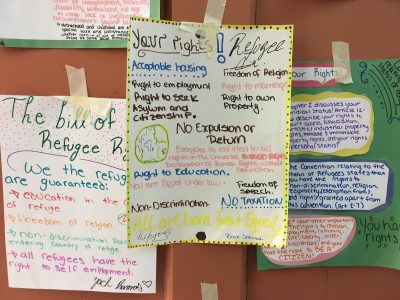

The piloted course – which was offered during the 2015-16 academic year at Manchester High School, East Hartford High School, and Woodstock Academy – is oriented around inquiry- and project-based learning. At Manchester High, for example, part of the coursework includes having students develop interactive exhibits around specific human rights issues — a miniature human rights “museum” of sorts that, Mitoma says, pushes students to translate the research skills they acquire into “practices that then help communicate, or make a point, about a particular human rights issue.”

“My ambition is to make Connecticut a national model for human rights education.” Glenn Mitoma, assistant professor of human rights and curriculum and instruction

Jacob Skrzypiec ’13 (ED), ’14 MA, a Neag School graduate and social studies teacher who began teaching the ECE course at Manchester High last fall, says the impact of the coursework on his own students is clear.

“Connecticut students in particular, many having lived their entire lives in somewhat isolated/independent hamlets of the state, divided by social, economic, and political limitations beyond their control, can sometimes have a narrow perspective on the world around them,” Skrzypiec says. “The reward for high school students taking a course or engaging in human rights education experiences is endless, as they can not only become greater global citizens, but can be nurtured to think, rationalize, and critique as engaged, focused participants of society. For me, the best is seeing my students gain a greater sense of empathy, compassion and understanding for others.”

In fact, the course has been so well received at Manchester High that, come the 2017-18 academic year, it will require all juniors to complete coursework in human rights in order to matriculate — a development about which Skrzypiec says he is particularly proud.

The success of the piloted course, from Mitoma’s perspective, has been twofold. “One is the demonstrated impact on students,” he says. “The students immediately begin making connections, looking to past examples and historical instances of either human rights abuse or human rights struggles to contemporary manifestations.” Seeing students begin to make these connections, Mitoma adds, “is always a mark that we’re having the kind of impact we want.”

Another measure of success is evident in the professional networking that has naturally developed among the ECE teachers, Mitoma says. For instance, fellow ECE teachers, including Skrzypiec, are now collaborating to organize a series of human rights conferences for high school students — to be hosted at UConn later this year — that are meant to foster discussion around human rights issues and to allow high schoolers to hear from experts in the field.

In light of its growing success over the past year, the course will now expand this fall to two additional partner high schools — Conard High School in West Hartford as well as Crosby High School in Waterbury. A second Neag School alum, Abigail Esposito ’14 (ED), ’15 MA, will be teaching the course at Conard.

“I am very happy that we can offer such an important and specialized course at the high schools,” says Brian Boecherer ’03 (CLAS), ’14 MA, executive director of Office of Early College Programs and ECE at UConn, who worked with Mitoma to launch the piloted course in Fall 2015. “This is a very important course for many students because I think it allows them to become aware of a major that is yet not well known. It also allows highly credentialed instructors at the high schools an academic home where they can feel part of something much larger.”

At the same time, Skrzypiec adds, giving high schoolers the opportunity to take a college-level human rights course “can push students to rise to the academic rigor expected in a collegiate course, while also allowing students to discuss and grapple with potentially controversial issues not otherwise touched in high school classrooms.”

To learn more about the human rights ECE course or ongoing efforts to expand human rights education and programming, contact Glenn Mitoma at glenn.mitoma@uconn.edu. Follow him on Twitter @GlennMitoma. Find more information about the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center at doddcenter.uconn.edu, or at @DoddCenter on Twitter and at facebook.com/doddimpact on Facebook.

Assistant Professor Glenn Mitoma also recently led the Upstander Academy, a weeklong research and engagement program for middle and high school teachers designed to examine the role that intellectual humility can play in meaningful public dialogue. Read more about the Upstander Academy here.