Research findings from Shaun Dougherty, assistant professor of educational leadership in the Neag School of Education, are the focus of two recently released reports focused on the topic of career and technical education (CTE), or what was once known as vocational education.

Each report — the first of which was released in late March by the Manhattan Institute and a second report, published earlier this month by the Thomas B. Fordham Institute — has seen a wealth of high-profile coverage in recent weeks, including numerous stories in Education Week, U.S. News & World Report, Diverse Issues in Higher Education, Hartford Business Journal, and a wide variety of other media outlets and education blogs. In addition, Dougherty and his Manhattan Institute report co-author, Opportunity America president and CEO Tamar Jacoby, published an op-ed for website New York Slant, and Dougherty penned a post for Fordham Institute’s Flypaper.

“We owe it to America’s students to prepare them for whatever comes after high school, not just academic programs at four-year universities.”

— Assistant professor Shaun Dougherty

The Manhattan Institute, titled “The New CTE: New York City as Laboratory for the Nation,” highlights the success of CTE programs specifically in New York City in recent years. Among the report’s key findings1:

- The number of New York City high schools dedicated exclusively to CTE has tripled since 2004 to almost 50; some 75 other schools maintain CTE programs; 40 percent of high school students take at least one CTE course, and nearly 10 percent attend a dedicated CTE school.

- Data on outcomes are still limited, but evidence suggests that young people who attend CTE schools have better attendance rates and are more likely to graduate; students in comprehensive high schools with CTE programs also appear to score better on standardized tests than those at schools with no CTE offerings.

- Following a decade of bold changes in city and state policy, the front lines of innovation have shifted from offices in Manhattan and Albany out to schools across the five boroughs, where educators are working—some more successfully than others—to implement the essential elements of the new CTE.

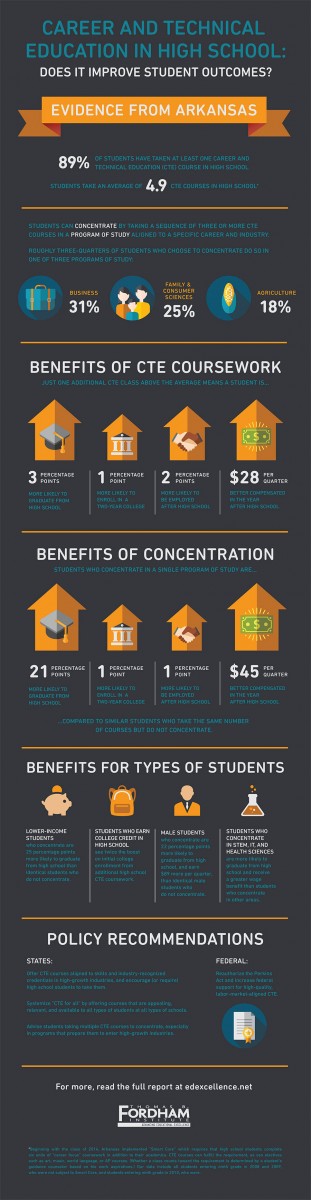

Meanwhile, in the Thomas B. Fordham Institute report — “Career and Technical Education in High School: Does it Improve Student Outcomes?” — Dougherty details the benefits reaped by students enrolled in CTE coursework in the state of Arkansas. As Dougherty asserts in the Fordham report: “There was a time when the ‘vo-tech’ track was a pathway to nowhere … [For American students,] not only do they lack access to high-quality secondary CTE, but then they are subject to a ‘bachelor’s degree or bust’ mentality. And many do bust, dropping out of college with no degree, no work skills, no work experience, and a fair amount of debt. That’s a terrible way to begin adult life. We owe it to America’s students to prepare them for whatever comes after high school, not just academic programs at four-year universities.”

Key findings2 include:

- Students with greater exposure to CTE are more likely to graduate from high school, enroll in a two-year college, be employed, and earn higher wages.

- CTE is not a path away from college: Students taking more CTE classes are just as likely to pursue a four-year degree as their peers.

- Students who focus their CTE coursework are more likely to graduate high school by twenty-one percentage points compared to otherwise similar students (and they see a positive impact on other outcomes as well).

- CTE provides the greatest boost to the kids who need it most—boys, and students from low-income families.

A selection of the report’s other key findings are illustrated in the infographic at right.

Following the Fordham Institute report’s release, Dougherty also presented this past week as part of a live-streamed follow-up session and panel discussion hosted by the Institute; the PowerPoint slides from the presentation may be downloaded here.

Access the Manhattan Institute report in full here, and the report from the Fordham Institute here.

On Twitter? Follow the conversation via the hashtag #CTErevisited, and be sure to follow Shaun Dougherty at @doughesm.