As 2017 nears its close, work on the University Principal Preparation Initiative (UPPI) — an initiative led at UConn by the Neag School’s University of Connecticut Administrator Preparation Program (UCAPP) — is getting ready to celebrate its first birthday. This past year, UConn was one of seven universities selected to take part in the Wallace Foundation-funded initiative, which launched officially in January and is focused on improving training programs for aspiring school principals nationwide. At UConn, UCAPP is a school leadership program based at the Neag School that prepares highly qualified school administrators in Connecticut.

Faculty from the Neag School, administrators from the Connecticut State Department of Education (CSDE), leaders from several public school districts in Connecticut, and other stakeholders from across the nation who have joined UConn’s UPPI workgroups are collaborating to address how university principal preparation programs — working in partnership with high-needs school districts, exemplary preparation programs, and the state — can improve their training so it reflects the evidence on how best to prepare effective principals. Over the past 10 months, these workgroups have been developing a “theory of action” for redesigning UCAPP that is focused on three main facets: revising the UCAPP curriculum, developing a leader tracking system, and redesigning the program’s internship component.

“UCAPP is universally recognized as a top program that creates opportunities and helps other programs. We’re looking to continuously improve the program so this momentum can keep up steam for years to come.”

— Richard Gonzales,

UPPI project director and principal investigator

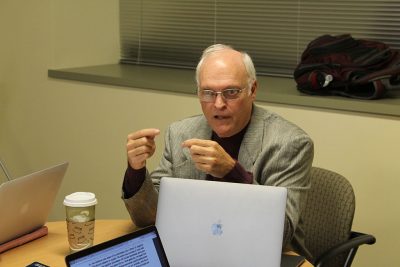

“The main question we’re asking here is: How can a traditional university program work with partners to redesign themselves and align with the best in the field?” says Richard Gonzales, project director and principal investigator for UPPI. Gonzales has coordinated the effort to redesign and improve the program so that the curriculum and the internship experience parallel each other more effectively.

For the Connecticut State Department of Education, this partnership will, according to Sarah Barzee, CSDE chief talent officer, allow for a “transformation through a targeted focus on principal preparation with the goal of ensuring that each and every principal enters this phase of their career with the knowledge, skills, and understanding to be a ‘school-ready’ principal.”

Curriculum Revision

The workgroup taking on revisions to the UCAPP curriculum has come together to review existing UCAPP curriculum materials, syllabi, and more in order to identify the programs’ strengths as well as areas of opportunity — with the ultimate goal in mind of proposing solutions and improvements where appropriate. The workgroup was co-chaired by Sarah Woulfin, assistant professor in the Neag School, and Erin Murray, assistant superintendent for Simsbury (Conn.) Public Schools.

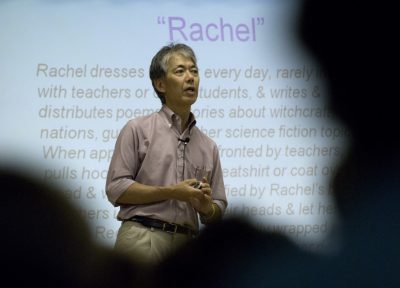

“Principals are no longer merely managers inside the office; rather, they are responsible for transforming teaching and learning to yield equitable outcomes for children, families, and communities,” say workgroup members in a self-assessment report they issued this past summer. “Wallace UPPI is grounded in the theory of action that if university-based principal preparation programs improve, then principals will be more effective leaders to promote positive educational outcomes.”

The report proposes a variety of short-term and long-term next steps and recommendations for improving the UCAPP curriculum, some of which could potentially involve piloting, testing, and refining new approaches. It also points out existing gaps in data collection and analysis, “acknowledg[ing] that the leader tracking system will enable the program to obtain additional data.”

Developing a Leader Tracking System

Meanwhile, the Leader Tracking System (LTS) is being developed to evaluate leadership development from the district, university, and state perspectives. The workgroup behind these efforts envisions using such a system to provide data to the Connecticut State Department of Education, partner districts, and the Neag School that would ultimately be used to make decisions about the preparation, hiring, development, and placement of school leaders.

According to Louis Bronk, director of talent at Meriden (Conn.) Public Schools and a co-chair for the UPPI workgroup focused on the LTS, the team is focused on figuring out what they are specifically looking for in school leadership, and what information and data they need to answer this question. A fully realized LTS would ultimately outline what qualities candidates must exhibit and what knowledge they must possess.

“From a university standpoint, the LTS would provide information on a candidate’s success post-graduation for the prep program,” says Bronk. “From a [school] district perspective, it will allow us to evaluate our internal leadership development systems and also allow us to better engage in data-driven decision making in regard to administrator placement and development.”

Internship Redesign

For UPPI’s internship workgroup, the goal has been “to bring coherence to all aspects of the internship across the three models of training within UCAPP,” says Jennifer Michno, co-chair of UPPI’s internship workgroup. The three models of training within UCAPP include a traditional track, designed for Connecticut-certified educators with at least three years of experience in teaching; a track known as Preparing Leaders for Urban Schools (PLUS), for educators working in Hartford or New Haven (Conn.) public schools; and a residency track, which is designed to prepare principal candidates to serve specifically in turnaround schools.

In its efforts to unite the internship component across UCAPP’s models, the workgroup will be looking, Michno says, not only to shift the internships from a focus on supervision to one on coaching, but also to bring measurability to all facets of the UCAPP internship at large and to decide on consistent practices and protocols that will be used across all UCAPP internships.

In addition, the workgroup is partnering on internship redesign efforts with a number of other collaborators from across the nation, including the New York City Leadership Academy, a nonprofit that prepares and supports educators to lead schools, and mentors assigned through the University of Illinois-Chicago.

As the UPPI project progresses, such collaborative efforts across each of the workgroups will continue to evolve. “UCAPP is universally recognized as a top program that creates opportunities and helps other programs,” Gonzales says. “We’re looking to continuously improve the program so this momentum can keep up steam for years to come.”

Learn more about the Neag School’s involvement in the University Principal Preparation Initiative (UPPI) and how it is working to transform principalship at s.uconn.edu/UPPI.

Related Stories: