K-12DIVE (Michael Young is quoted on the benefits of educators using metaverse)

UConn Faculty Winning NSF CAREER Awards at Record-Breaking Pace

CT Mirror (Ido Davidesco, the first Neag School faculty to earn CAREER funding, is mentioned)

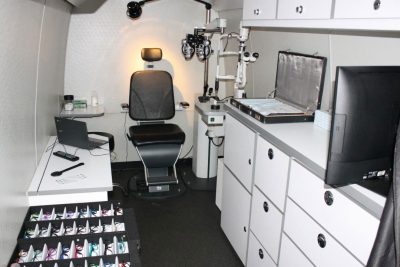

Partnering to Give Local Schoolchildren the ‘Vision To Learn’

For East Hartford Silver Lane Elementary School first-grader A’miyah Diaz and many of her classmates, getting prescription eyeglasses has been nothing but cause for celebration.

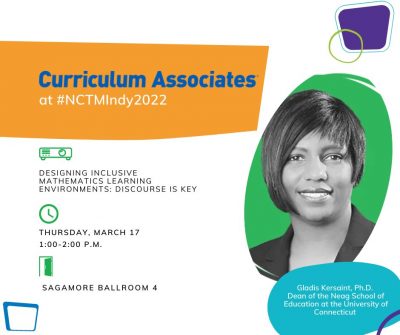

Thanks to an effort spearheaded by UConn Vice Provost for Strategic Initiatives Gladis Kersaint, Neag School professor and former Neag School dean, students across Connecticut are receiving free vision screenings, eye exams, and, for those in need, prescription eyeglasses as well.

Initiating a conversation that led to the partnership of national nonprofit Vision To Learn with sponsors including Dalio Philanthropies, Connecticut Sun, and UnitedHealthCare, Kersaint saw a valuable opportunity that would serve children across the state.

To date, Vision To Learn has provided vision screenings to more than 2,400 students in East Hartford’s elementary schools. From these screenings, close to 900 students were identified in need of an eye exam, and so far, roughly 350 students have been provided a free eye exam on a mobile clinic. Students who need glasses then select their brand-new frames. Vision To Learn returns to the school in about a month to dispense and fit the glasses to each student.

“Providing eye exams and glasses to students was an easy sell to everyone I spoke with,” Kersaint said at an event held last week at Silver Lane Elementary that brought together East Hartford mayor Mike Walsh, Connecticut’s Lieutenant Governor Susan Bysiewicz, representatives from the Connecticut Department of Education and numerous other agencies, as well as local parents.

“Providing eye exams and glasses to students was an easy sell to everyone I spoke with.”

— Gladis Kersaint, UConn Vice Provost for Strategic Initiatives

There, students including Diaz stood at the front of the gymnasium, donning their new eyeglass frames for the first time and marveling at their reflections. “They look cute!” Diaz exclaimed after receiving the new blue frames she had chosen.

“I am most excited for you, the students, who will receive glasses today and who will advance your learning by participating fully and seeing and engaging in the work,” Kersaint told the children in the audience.

“As many of you are aware, for the past couple of years, we faced a number of challenges both as a school and as a community,” said Joe LaBarbera, principal of Silver Lane Elementary. “Today, one of the challenges will no longer be our kids’ ability to see the board or the ability to read the text in front of them.”

East Hartford Superintendent and Neag School alumnus Nathan Quesnel ’01 (ED), ’02 MA, who emceed the event, was quick to credit the Neag School for bringing the effort to fruition for the students in his district.

“I’m really proud of today,” he said. “It’s a culmination of when you have an idea, you implement it, and then you have moms and dads who are sitting in the back watching their kids being showered with love and care.

“We [work to] ‘weave webs of empowering support around kids,’ and an example of that is here,” he added. “I’m just appreciative of the Neag School and obviously to Gladis and Jason [Irizarry, current dean] for thinking of us and being much bigger than just words – they are taking action.”

“We are excited to bring free vision services to Connecticut’s children and fortunate to have Dr. Gladis Kersaint as one of strongest champions,” says Sabrina A. Davis, program manager for Vision To Learn in Connecticut.

Vision To Learn recently marked its 10th anniversary. Over the past decade, Vision To Learn has helped provide more than 1.5 million children with vision screenings, upwards of 340,000 with eye exams, and 270,000 with glasses — all free of charge to children and their families.

In Connecticut, Vision To Learn also serves students in Ansonia, Vernon, Manchester, East Haven, Winchester, and Thompson Public Schools, in addition to community organizations in the summer. For more information on Vision To Learn, please visit visiontolearn.org.

Neag School Named a Top 20 Public Graduate School of Education

UConn’s Neag School of Education appears for the seventh consecutive year as one of the top 20 public graduate schools of education in the United States, tied at No. 17, per the 2023 U.S. News & World Report rankings released earlier today.

UConn’s Neag School of Education appears for the seventh consecutive year as one of the top 20 public graduate schools of education in the United States, tied at No. 17, per the 2023 U.S. News & World Report rankings released earlier today.

Among all graduate schools of education across the nation, the Neag School stands at No. 28, while its special education program is tied at No. 17 in the U.S. News 2023 specialty program category rankings.

“Our faculty and staff are at the heart of our mission here at the Neag School of Education — to improve educational and social systems to be more effective, equitable, and just for all,” says Dean Jason G. Irizarry.

“Recognition as one of the nation’s foremost graduate schools of education is one more testament to their level of dedication to that work, as we strive to prepare teachers, school administrators, research scholars, counselors and school psychologists, sport management professionals, and leaders who are well informed, globally minded, and equipped to address the most critical issues facing our communities today.”

U.S. News collected statistical and reputation data in Fall 2021 and early 2022 from education schools nationwide that grant doctoral degrees in education; of 457 schools surveyed, 274 responded. Eleven different indicators, including total research expenditures, student selectivity, and assessment scores by peers, are used in the rankings calculations. Specialty rankings are based on nominations by deans of education schools and deans of graduate studies at education schools from the list of schools surveyed, according to U.S. News.

Check out the 2023 U.S. News Best Education Schools rankings online.

2022’s Most and Least Stressed States

Wallet Hub (Lisa Sanetti quoted about fighting stress without spending money)

Creating Brand Champions Is the True Power of Web3

ADWEEK (Neag School alumna and co-founder of CatalystU Amanda Slavin pens essay on brand management)

North Stonington Names New Superintendent

The Day (ELP alumnus Troy Hopkins featured)

South Windsor Administrator Named Region 8 Superintendent

South Windsor Patch (ELP alumnus Colin McNamara featured)

Geoff Johnson: Giftedness Isn’t Just About IQ

Time Colonist (Joseph Renzulli is quoted on the definition of gifted kids)

Neag School Accolades: March 2022

Throughout the academic year, the Neag School is proud to share the latest achievements of its faculty, staff, students, and alumni.

Explore their most recent promotions, research grant announcements, publications, and more:

- Dean’s Office

- Department of Curriculum and Instruction and Teacher Education

- Department of Educational Leadership

- Department of Educational Psychology

- Faculty/Staff

- Students

- Alumni

- In Memoriam

Dean’s Office

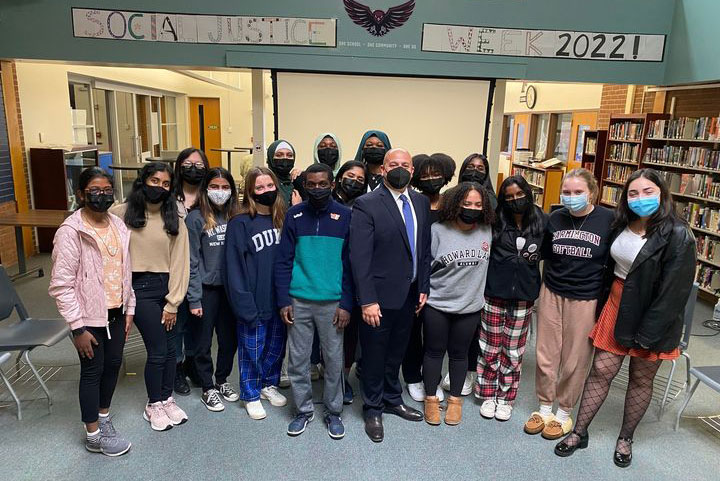

Dean Jason G. Irizarry visited Farmington (Connecticut) High School in February as a guest of Principal Scott Hurwitz ’93 (CLAS), ’08 6th Year. The tour included observing Neag School teacher education seniors doing student teaching in their classrooms, along with attending presentations and a discussion about Farmington High’s Social Justice Week. View photos from the visit.

The Neag School of Education collaborated with UConn Women and Philanthropy to host “ELLEvate: Supporting Women in Leadership,” a panel discussing women’s experiences in leadership roles. Laura Burton served as the moderator, and Neag School alumni Fany Dejesus Hannon ’08 MA and Vonetta Romeo-Rivers ’04 6th Year, ’14 ELP participated as panelists. The virtual panel was held in February. Read more about the panel.

Neag School of Education faculty and district partners participated in an EdPrepLab Learning Café series titled “Leveraging EdPrepLab to Strengthen Educator Preparation: Faculty Engagement and District Partnerships.” The virtual event was held in February. Michele Femc-Bagwell, Thomas Levine, Niralee Patel-Lye, and alumni Robert Testa ’04 6th Year, assistant superintendent for Vernon (Connecticut) Public Schools, and Bonnie Fineman ’11 6th Year, director of arts and humanities for Windsor Public Schools, were presenters.

Tamika La Salle was recognized with the 2022 Dr. Perry A. Zirkel Distinguished Teaching Award, which is awarded annually to a full-time faculty member in the Neag School for outstanding teaching. La Salle was formally recognized during the 2022 Neag School Alumni Awards, held virtually in March. Check out the webpage featuring honorees from the event.

The Neag School of Education was a sponsor for UConn Women and Philanthropy’s “Fast Fierce Women” event featuring UConn faculty member and notable author Gina Barreca. The list of contributors included Neag School alumni Courtney Baklik ’11 (CLAS), ’12 (ED), ’17 MA; Ebony Murphy-Root ’04 (CLAS), ’10 MA; Nicole Decker ’05 (CLAS), ’07 CAHNR, ’08 MA; Jennifer Rizzo ’10 (CLAS), ’11 MA; and Danielle Waring Bernardo ’00 (ED), ’01 MA. View the event recording here.

The Neag School of Education was a sponsor for UConn Women and Philanthropy’s “Fast Fierce Women” event featuring UConn faculty member and notable author Gina Barreca. The list of contributors included Neag School alumni Courtney Baklik ’11 (CLAS), ’12 (ED), ’17 MA; Ebony Murphy-Root ’04 (CLAS), ’10 MA; Nicole Decker ’05 (CLAS), ’07 CAHNR, ’08 MA; Jennifer Rizzo ’10 (CLAS), ’11 MA; and Danielle Waring Bernardo ’00 (ED), ’01 MA. View the event recording here.

The Neag School and its Alumni Board celebrated the 2022 Alumni Awards Celebration winners earlier this month. Watch the event recording and check out the webpage featuring each honoree.

Department of Curriculum and Instruction (EDCI)

This spring, the Connecticut Noyce Math Teacher Leaders (MTL) Program welcomed a cohort of 20 veteran mathematics educators from across the state during a kickoff event in March that included remarks by Dean Jason G. Irizarry. Funded by the National Science Foundation and private donors, the MTL Program, led by Megan Staples with co-PI Gladis Kersaint and doctoral student Kenya Overton as program manager, will engage these teachers from numerous Alliance Districts in a five-year professional learning and service program. View photos from the event.

Carlton Jones and graduate student Tamashi Hettiarachchi ’21 (ED) were featured in an epsiode of the UConn Office of First Year Programs’ podcast “My First Year Story.”

Department of Educational Leadership (EDLR)

The Center for Education Policy Analysis, Research, and Evaluation (CEPARE) hosted a speaker series featuring Lauren C. Mims from Ball State University, who spoke about exploring Black brilliance and creative problem solving in fugitive home spaces. The event was held virtually in February.

A report titled “Evaluation of the State of Connecticut Summer Enrichment Grants,” submitted by CEPARE faculty, including Casey Cobb and Dorothea Anagnostopoulos, along with doctoral students Kiah DeVona and Kenya Overton, was referenced during Gov. Ned Lamont’s press conference in March in Hartford, Connecticut. The report examined how Connecticut’s summer enrichment grants helped reengage students in time for the return of in-person learning last fall.

The Sport Management Program hosted a “Beyond the Field” virtual event in March on sport and corporate social responsibility, with Eli Wolff moderating the discussion.

Department of Educational Psychology (EPSY)

The Renzulli Center for Gifted Education, Creativity, and Talent Development has been hosting free webinars for parents and educators on a variety of gifted education-related topics, led by Neag School faculty, alumni, and other experts in the field.

Faculty/Staff

Cara Bernard was recognized with a University Teaching Fellow Award from UConn’s Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning. This honor has been bestowed on a small number of faculty who are part of a selective club of distinguished educators recognized and respected for teaching excellence. She will be recognized at a ceremony later in the semester.

Jacqueline Caemmerer co-published “Computer-enhanced Practice: The Benefits of Computer-assisted Assessment in Applied Clinical Practice” for the 2022 issue of Professional Psychology: Research and Practice.

Todd Campbell and David Moss, along with doctoral student Jonathan Simmons ’11 (CLAS), ’02 MA, co-authored with others “Pivoting During a Pandemic” for the March-April issue of Connected Science Learning (a publication of the National Science Teaching Association).

Milagros Castillo-Montoya co-published “Why the Caged Bird Sings in the Academy: A Decolonial Collaborative Autoethnography of African American and Puerto Rican Family Faculty and Staff in Higher Education” for the 2022 issue of Journal of Diversity of Higher Education.

Sandra Chafouleas was featured in a podcast episode on multi-tiered trauma informed support for Where We Live’s Trauma Informed Education with Dr. Kay Ayre. Chafouleas was also co-editor of a special topic issue of School Psychology Review and wrote an essay titled “Pandemic-Related School Closings Likely to Have Far-Reaching Effects on Child Well-Being” for The Conversation.

Chen Chen contributed to the creation of UConn’s inaugural Confronting Anti-Asian Racism pop-up course and also has been invited to serve on the editorial board of the Sociology of Sport Journal.

![People attending school board meeting holding signs. [Links to story in The Conversation.]](https://education.media.uconn.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/1621/2022/01/Cobb_PM-400x267.jpg)

Michael Coyne was a lead author for a chapter titled “Structured Literacy Interventions for Vocabulary” in Structured Literacy Interventions (Guilford Press, 2022).

Morgaen Donaldson co-directs the Connecticut COVID-19 Education Research Collaborative (CCERC), which was recently recognized by EduRecoveryHub for its commitment to studying and evaluating its K-12 recovery investments and publicly reporting findings.

Justin Evanovich and Jennie McGarry co-authored with others “Youth Perceptions of Sport-Confidence” for the November issue of Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research.

Doug Glanville wrote an essay titled “Why I’m Okay With Barry Bonds Not Being Elected to the Hall of Fame” for ESPN.com.

Jason Irizarry co-published a chapter titled “Redirecting the Teacher’s Gaze: Teacher Education, Youth Surveillance and the School-to-Prison Pipeline” in System Failure: Policy and Practice in the School-to-Prison Pipeline (Routledge, 2022).

James Kaufman co-published chapters titled “Theories of Creativity” and “Creativity and Mental Illness” in Creativity and Innovation Theory, Research, and Practice (Routledge, 2022). Kaufman also co-published “Positive Creativity in a Negative World” for the February issue of Education Services.

Devin Kearns was a lead author, with doctoral students Cheryl Lyon and Shannon Kelley as co-authors, for a chapter titled “Structured Literacy Interventions for Reading Long Words” in Structured Literacy Interventions (Guilford Press, 2022). Upon its release, the volume ranked as the No. 1 special education title on Amazon.

Devin Kearns was a lead author, with doctoral students Cheryl Lyon and Shannon Kelley as co-authors, for a chapter titled “Structured Literacy Interventions for Reading Long Words” in Structured Literacy Interventions (Guilford Press, 2022). Upon its release, the volume ranked as the No. 1 special education title on Amazon.

Alan Marcus recently published a research study in Holocaust Studies that examined the tradition of Holocaust education shifting from live to virtual survivor testimony. The research was featured in UConn Today.

Betsy McCoach co-hosted a session titled “Deep Dive on Open Practices: Understanding Registered Reports” for the Center for Open Science’s virtual UNCONFERENCE 2022 in February. McCoach also co-published with Neag School alumna Sarah D. Newton ’18 MA, ’20 Ph.D. and doctoral student Anthony J. Gambino, a chapter titled “Evaluation of Model Fit and Adequacy” for Multilevel Modeling Methods with Introductory and Advanced Applications (Information Age Publishing, 2022).

Adam McCready was named an affiliate faculty member of the UConn Center for mHealth and Social Media.

H. Kenny Nienhusser co-published “When I Would Hurt”: Undocumented Students’ Responses to Obstacles Faced During the College Choice Process” for the January issue of The Educational Forum.

Joseph Renzulli was recognized among Global Gurus’ Top 30 Education Professionals for 2022 (No. 3).

Joseph Renzulli was recognized among Global Gurus’ Top 30 Education Professionals for 2022 (No. 3).

Stephen Slota was featured by UConn Magazine about books he is reading.

Tracy Sinclair was a co-presenter for a webinar in February on “Assessment for Transition Planning” for the American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (AAIDD).

Megan Staples and colleagues, including alumni Maria Enrique ’16 BS/BA, ’17 MA; Sherryl (Hauser) King ’07 BS, ’08 MA; and Brian McDermott ’08 BS, ’09 MA, published a digital volume titled Connecting Mathematics and Social Justice: Lessons and Resources for Secondary Math Teachers. Staples also co-edited a book Conceptions and Consequences of Mathematical Argumentation, Justification, and Proof (Springer Link, 2022), in which she also published a chapter “Overview of Middle Grades Data” and co-published chapters “Introduction: Conceptualizing Argumentation, Justification, and Proof in Mathematics Education” and “Justification Across the Grade Bands.”

Jennie Weiner co-published “Theorizing School Leadership as a Profession: A Qualitative Exploration of the Work of School Leaders” for the February issue of Journal of Educational Administration. She also co-published “Negotiating Incomplete Autonomy: Portraits from Three School Principals” for the February issue of Educational Administration Quarterly. In addition, Weiner, along with Laura Burton and doctoral student Daron Cyr, published research on exploring the role of Black female principals in schools, which was featured in UConn Today.

Eli Wolff was featured in a UConn Today story “Olympic Athletes: Five Questions America Needs to Ask About Athlete Activism.” Wolff also co-wrote an essay titled “What’s the IOC – And Why Doesn’t It Do More About Human Rights Issues Related to the Olympics,” for The Conversation.

Students

Christophe Graupner ’21 (CLAS), a master’s student in French education, participated in “Ask Away: 5 Questions for a Connecticut-based Future Teacher From Troyes, France” for Lead with Languages, the advocacy arm of ACTFL.

Manny Hatzikostas ’20 (ED), a master’s student in sport management, started a new position as director of softball operations/assistant director of communications at UConn. He previously served as director of UConn men’s soccer operations.

Georgia Mikan, a junior elementary education student, is a recipient of the inaugural Nom and Boulieng Vorsane Scholarship.

Katerine Santiago Montalvo ’21 (ED), a master’s student and intern with the Connecticut Council of Language Teachers, participated in a “CT COLT: Tip of the Week” where she shared her insights about her upcoming study abroad in Peru.

Karla Rivadeneira ’21 (ED), a master’s student and intern with the Connecticut Council of Language Teachers, participated in a “CT COLT: Tip of the Week” showing how she uses TikTok as a hook to start student conversation or to get them writing. Rivadeniera also published “Ask Away: 5 Questions for a Heritage Speaker & Future Spanish Educator” for Lead with Languages.

Kat Santiago ’21 (CLAS), a master’s student and intern with the Connecticut Council of Language Teachers, participated with a “CT COLT: Tip of the Week” where she showed how she engages with students through multimedia.

Lynna Vo, a pre-teaching Neag School student, is a recipient of the inaugural Nom and Boulieng Vorsane Scholarship.

Doctoral student Emily Winter co-published with Melissa Bray and colleagues a chapter titled “Physical Health as a Foundation for Well-Being: Exploring the RICH Theory of Happiness” in Handbook of Health and Well-Being (Springer, 2022).

Alumni

Peter Dart ’09 6th Year, ’16 ELP was selected as Mansfield (Connecticut) Public Schools’ next superintendent. Dart, who has served as principal of Mansfield’s Dorothy C. Goodwin Elementary since 2018, will succeed Neag School alumna Kelly Lyman ’92 MA, ’93 6thYear, effective July 1, upon her retirement.

Steven Feldman ’20 MA recently joined an LGBTQ Center Research Collective, consisting of scholars and LGBTQ Center practitioners across the country, in conducting participatory action research on the needs and experiences of LGBTQ Centers on college campuses.

Sydney Gibbs ’19 (ED) started a new position as an account executive, membership sales, with the Brooklyn Nets. Gibbs previously worked for the Boston Red Sox as an inside sales representative. As a student at UConn, Gibbs was a member of the UConn women’s rowing team.

Fany Hannon ’08 MA, director of UConn’s Puerto Rican/Latin American Cultural Center (PRLACC), was featured in a UConn 360 podcast episode about PRLACC’s 50th Anniversary.

Ryan Haynes ’20 MA is a residence life coordinator at Pomona College in Claremont, California. Before that, he worked as a student services specialist for College Living Experience.

Brittany Hunter ’08 (ED), ’11 MS was promoted to business manager for Azure Core at Microsoft. She previously served in talent management and as an HR program manager at Microsoft. As a UConn student, Hunter was on the UConn women’s basketball team.

Joey Kopriva ’14 MA was promoted to director of residential life at Columbia University. Kopriva has been in residential life at Columbia for the past seven years and most recently served as the associate director.

Jake Krul ’17 (ED) was promoted to assistant director of development in athletics for the UConn Foundation. He previously served as an assistant director of athletic external relations for the UConn Foundation.

Xiaochen Liu ’16 MA, ’20 Ph.D. was featured by the UConn Center for Career Development. Liu works as a faculty development specialist at UConn’s Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning and offers remote support to faculty, students, and staff at Schwarzman College at Tsinghua University (China).

Leah Lum ’18 (ED) was a member of Team China’s women’s hockey team at the Olympic Winter Games in Beijing.

Brianna Miloz ’19 MA recently co-authored a book chapter titled “Damned If You Do, Damned If You Don’t: The Trials and Tribulations of Multiracial Student Activism” as part of the larger piece of scholarship, Preparing for Higher Education’s Mixed Race Future.

Linda Pescatello ’01 (CLAS), ’81 MA, ’86 Ph.D., a faculty member in UConn’s kinesiology department, formerly housed within the Neag School, was profiled by UConn Today.

Willena Kimpson Price ’90 Ph.D. was profiled by the Neag School, recognizing her almost 30-year career as director of the H. Fred Simons African American Cultural Center.

Alfredo Ramirez ’19 MA began a new role as a corporate training specialist with City Experiences. In this role, Ramirez is working alongside the director for learning and development to create new learning and development content and facilitate leadership training throughout the company. Ramirez previously worked as the assistant director for programs and marketing at Temple University.

Maureen (McSparran) Ruby ’77 (CLAS), ’78 MS, ’82 DMD, ’07 Ph.D. was selected by Sacred Heart University as its first endowed chair – the Isabelle Farrington endowed chair of social, emotional, and academic leadership. She most recently served as the assistant superintendent in Brookfield, Connecticut.

Lois Greene Stone ’55 (ED) is featured at the Smithsonian’s American History Museum’s exhibit “Girlhood,” which focuses on American teens in the 1950s. The photo shows Stone as a teen during homecoming, taken in her UConn dorm in 1954, showing off her clothing designs.

Marty Summa Jr. ’12 (ED) was promoted to director of digital media and social strategy for Sage Growth Partners (SGP). He has been with SGP since 2020 and oversees digital marketing and social media efforts for clients. Before SGP, he served as a senior director of social/digital media and branding for the University of Maryland’s athletic department.

In Memoriam

Russell M. Agne ’70

Kathleen M. Altieri ’96

Algird A. Arison ’56

Janice A. Bittner ’73

Patrick M. Brown ’80

Kathleen Coe

George DeLeone ’70

Rosemarie Dion ’81

Anna Mae DuCharme ’61

Alan R. Elrick ’56

Theresa M. Ferguson ’80

William Gregonis

Virginia S. James ’88

Samuel S. Johnson ’69

Margo J. McGeary ’60

Karl A. Monty ’73

Janet (Crawford) A. Nichols ’58

Aleathia D. Nicholson ’65

Harriet A. Nirenstein ’66

Lillie E. Perkins ’75

Patricia A. Pinney ’98

Robert “Bob” Ricci ’73

Paula I. Robbins ’77

Thelma S. Samuel ’68

William A. Sarrell ’73

Carolyn H. Sutton ’76

Elizabeth A. Ward ’62