K-12 DIVE (Michael Young is quoted about online learning and educational gaming)

Lack of Teacher Diversity Takes Focus Amid Teacher Shortage

Hartford Courant (Neag School alums, Marquis Johnson and Kate Dias, are quoted)

Celebrating the 2022 Neag School Alumni Awards Honorees

Milwaukee Carmen Union Drive Shows How Charter Schools Straddle Public and Private Sectors

WUWM: Milwaukee’s NPR (Preston Green is quoted on charter schools)

Researchers Explore Role of Black Female School Principals

Editor’s Note: This article about the role of Black female principals, with research by Jennie Weiner, Laura Burton, and doctoral student Daron Cyr featured, originally appeared in UConn Today.

The challenges of the past two years have increased the demands of the job in ways both public and personal.

The twin events of the COVID-19 pandemic and a heightened awareness of racial inequities in the United States have further cemented the commitment of female Black school principals to their schools, according to a recent journal article published by three UConn scholars from the Neag School of Education.

“We are clearly in a period of turmoil right now for a variety of reasons, but predominantly because of issues of COVID and racial injustice, and statistically these subjects impact Black and brown communities in deeper ways than others,” says Jennie Weiner, an associate professor in educational leadership. She performed the research along with Laura Burton, a professor and the department head of educational leadership, and Daron Cyr, a doctoral candidate.

“We are clearly in a period of turmoil right now, but predominantly because of issues of COVID and racial injustice, and statistically these subjects impact Black and brown communities in deeper ways than others.”

— Associate Professor Jennie Weiner

The trio interviewed 20 Black female principals in three different states on multiple occasions before writing the report. The interviews started in person before the COVID-19 pandemic and were followed up with virtual meetings. The research also began before the murder of George Floyd and the national outcry that followed.

“Though these women play a pivotal role in the lives of so many children and families and face tremendous challenges in doing so, there just isn’t that much research about their experiences and their day-to-day life,” says Weiner. “We just don’t know much about their thinking, their doing, and their ways of being. As a result, it is hard to support them and provide the best resources for them to thrive.”

The team initially did a pilot study funded through the Initiative on Girls and Women in the administration of President Barack Obama and later gained funding through The Spencer Foundation.

“Many of the women we spoke to said that no one had ever come to them and asked them about their experiences, which is a travesty,” says Weiner. “Many of these women have been serving in education for 20 or 30 years, and have seen and done so much we can and should be learning from.”

“Many of the women we spoke to said that no one had ever come to them and asked them about their experiences.”

— Associate Professor Jennie Weiner

COVID and the increased awareness of racial injustice changed the dynamics of the research but did not deter the work.

“We were responsive to what people were facing and instead of pretending it wasn’t there, we dug in. The way we approached the research provided us this flexibility,” says Weiner. “We had spent two to three hours talking to each person at their school, so by the time we were not able to see them in person, we had built some rapport and trust.”

The researchers also took the unusual step in convening the women they interviewed and presenting them with the initial findings in draft form.

“What people are reading is actually co-constructed by the researchers and the participants,” says Weiner. “It was powerful for me as a researcher that the women shared in how they were to be represented and to help people understand their experiences in a real and authentic way. I am very proud of this piece and our approach because all the women signed off on it and the findings are representative of their experiences.”

Weiner studies leadership in kindergarten through 12th grade and is interested in how to make leadership more equitable and inclusive.

“I am interested in how to create organizations where people have the means to grow, learn, develop and change over time,” says Weiner. “Leadership has not always been that way because there is an elevation of a great man hero orientation toward leadership and that is situated in ideas about men being leaders, and white men specifically. I want to create opportunities for counter-narratives to that and spaces where we can talk about the ways women and women of color experience leadership, their ability to thrive in those spaces, and how gender discrimination and gendered racism play a role in that.”

The researchers found that the female Black principals fought for their schools and students despite the challenges they faced in their personal lives.

“Quite of few of these women were immuno-compromised themselves and a lot of them are primary caregivers for children or even adults,” says Weiner. “They put themselves are a great risk to ensure the caretaking of their communities. Sometimes this was despite being situated in districts where they felt like their individual school and its students were not being attended to properly.”

Weiner points to examples like principals making sure their school was a food distribution location, even if their school was the only one in the district to require such support. In addition, principals also spent nights putting together hard-copy paper homework packets together for students that did not have proper access to the internet.

“These women have proved, as they always have, that they care and do whatever is necessary to be beacons to lead others and to support their school families,” says Weiner. “I don’t think that a system that is dependent on groups that are marginalized to do more than everyone else is fair or equitable. I think that question is, how do we lift up these stores while not reinforcing the idea that it is appropriate for certain groups to have to do more than others?

“We need to provide more opportunities to get these people together and feel supported in meaningful ways. They need to feel a space of safety and connection and we need to attend to institutional racism and discrimination in ways that don’t put the burden of the work on those who are most affected by the injustice.”

Vision, Your House in Order, and an Extra $20K: What It Now Takes to Hire a Superintendent

Education Week (Bob Villanova is quoted on hiring superintendents)

Women Leaders Share Insights Through UConn ELLEvate Panel

The University of Connecticut’s Neag School of Education collaborated with UConn Women and Philanthropy this past Thursday to host “ELLEvate: Supporting Women in Leadership,” a panel discussing women’s experiences in leadership roles.

The panel, led by Laura Burton, department head and educational leadership professor at the Neag School, included Fany DeJesus Hannon, director of the Puerto Rican/Latin American Cultural Center (PRLACC) at UConn; and Vonetta Romeo-Rivers, director of teaching and learning for Regional School District 10 in Connecticut. Both Hannon and Romeo-Rivers are alumni of the Neag School.

Sharing How They Lead

For Fany Dejesus Hannon ’08 MA, who immigrated to the United States at the age of 20 from Honduras, many of the leadership strategies she has developed stem from her personal background and experience.

“I lead as a Latina,” said Hannon. “I come from a collective, loving family that values love, respect, and trust. I believe in the power of the ‘we’; I believe that I cannot do my job as a leader without my tribe, without my village, and I own that.”

The individualist mindset more typical of U.S. culture, she said, has challenged her in this way of thinking; however, Hannon’s childhood in Honduras instilled in her the power of collective thinking.

Hannon says she views her colleagues as her chosen family and stresses the importance of appreciating and acknowledging those who work and lead alongside you.

Many of Hannon’s messages were echoed by Vonetta Romeo-Rivers ’04 6th year, ’14 ELP. Romeo-Rivers also immigrated to the U.S., having been raised in Trinidad. In her current educational leadership role, she works to brings forth values of openness, honesty, and transparency that were instilled during her childhood. She encourages people to bring their whole self to work.

“Sometimes when you are that lone voice, that voice that is not typically represented in leadership conversations, it takes a certain type of courage and vulnerability to put yourself out there to ensure that those considerations are also at the table,” she said.

Learning and Remembering Your Why

During their leadership roles and professional careers, both Hannon and Romeo-Rivers remember their grounding “why.”

As a student at Smith College, Hannon says she did not have any Latinx individuals to look up to as role models, but she did have a strong mother who had imparted to her the value of education.

Hannon says the love and passion she has for her students allows her to work in an environment that she genuinely loves and to which has devoted her entire career.

“What motivates me, what gets me out of bed every day, is to see the transformation in our Latinx students,” she said. “I love them. They are the reason why I get up every morning to do this work; I love seeing them finding who they are.”

“What motivates me, what gets me out of bed every day, is to see the transformation in our Latinx students.”

— Fany Dejesus Hannon ’08 MA

Growing up in Trinidad, Romeo-Rivers was surrounded by a community and culture that valued education and teachers. She soon learned that being an educator was a job filled with honor and respect.

“It was part of my upbringing to see and feel that joy and love and appreciation for the profession, so that’s what I knew,” she said.

Like Hannon, Romeo-Rivers finds watching individuals grow and evolve one of the most beautiful parts of her job.

“I love educating, I love kids, I love seeing the shift, the growing; I love earning their trust, I love seeing them bloom and blossom and evolve as they grow, not only academically, but [as they] find out and figure out who they are,” she said.

Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, Romeo-Rivers said she and her colleagues reminded one another why they were doing this work, and most importantly, for whom.

“When you remember for whom you are doing this work, that is how you push through the psychological weight of the invisible labor; that’s how you push through the self-doubt and the imposter syndrome,” she said.

Working Within a Male-Dominated Society

Despite the joys of working with students, both panelists shared, there are still many moments when, as women, they are forced to break barriers in order to be heard. They acknowledged the daily struggles of working a leadership role within a male-dominated society.

“Within the past four years, someone said to me that I am not an executive leader, that I don’t know how to be one,” said Romeo-Rivers. “That person implied that I haven’t worked at that level of leadership before, and it’s not necessarily my fault that I don’t know how to be an executive leader.”

“There are so many times during the day that you have to re-center, that you have to take a breath, that you have not to be demeaned or diminished or muffled or silenced, and you have to find a way to navigate a system that may not want you there to begin with,” said Romeo-Rivers.

“You have to find a way to navigate a system that may not want you there to begin with.”

— Vonetta Romeo-Rivers ’04 6th year, ’14 ELP

Through such interactions, Romeo-Rivers says she has noticed the importance of learning what to take and what to leave, especially from those looking from the outside in.

“Thank God I didn’t have to depend on those opinions of those people to know my value and my worth to my profession and the career that I have dreamed of since I was a little girl in Trinidad,” she said. “Thank God I had things to anchor me, and it wasn’t that.”

When Hannon first began as director at PRLACC, she says she was often dismissed because of her age. Her willingness to be vulnerable and show emotion was also often a topic of discussion amongst her colleagues.

But it was during that first year that Hannon says she chose to define herself, rather than let others define her.

“I said to myself, I will lead the way that Fany DeJesus Hannon has to lead,” she said. “I embrace my vulnerability, and when it’s time to cry, I will cry.”

Instead of having to choose between openness and objectivity, Romeo-Rivers and Hannon stressed the possibility of embracing both at once.

“I can be both a vulnerable leader and strategic; I can be both outcomes-driven and still write handwritten notes to folks; I can still be brave enough and courageous enough to have hard and difficult, but necessary conversations, but I can still dress to the nines while I do that,” said Romeo-Rivers. “I can hold people accountable for our shared goals and move the needle towards those shared goals, but I shouldn’t have to worry so much about likability while I do it.”

Biden Supreme Court Nominee, Praised for ‘Stellar Civil Rights Record,’ Could Face Conflict on Upcoming Harvard Admissions Case

The 74 Million (Preston Green is quoted about the Supreme Court nominee)

Neag School 2022 Commencement Weekend Schedule

What’s the IOC – and Why Doesn’t It Do More About Human Rights Issues Related to the Olympics?

Editor’s Note: This article originally found on The Conversation, is co-authored by the Neag School’s Eli Wolff, answers five questions about the International Olympic Committee (IOC) and how they respond to human rights and other issues.

The International Olympic Committee, a nongovernmental organization based in Switzerland that’s independent of any one nation, was founded in 1894. It’s a group of officials who supervise and support the Olympics and set Olympic policies about everything from whether break dancing can be added as an official sport to what’s required for an athlete to compete on a team representing a country where they don’t normally reside. Because the IOC is often in the news, we asked two sports scholars, Yannick Kluch and Eli Wolff, five questions about what it does and why so many people want it to change how it responds to concerns about human rights and other issues.

1. What are the main things the IOC does?

The IOC coordinates what’s known as the Olympic movement, the technical term for the constellation of committees, federations, and other bodies that puts on spectacular sporting competitions every two years.

That includes overseeing the 206 national Olympic committees and 35 international sports federations. The IOC also supervises the specific organizing committees formed for every one of the Olympic Games, seven years before the competitions begin.

The IOC’s 101 members, many of whom are former athletes, meet at least once a year to make important decisions.

We believe good journalism is good for democracy and necessary for it.

They’re responsible for selecting where future Olympic Games will occur, electing their leaders, choosing new Olympic sports, and making amendments to the Olympic Charter. The IOC’s own officials select candidates for membership in the committee.

Thomas Bach, a German, has served as IOC president since 2013. He regularly convenes its executive board. He represents the IOC during the Games.

The IOC also oversees several humanitarian initiatives such as Peace and Development through Sport, the Olympic Refugee team, and the Olympic Solidarity program. The committee has observer status with the United Nations and promotes a worldwide symbolic ceasefire during the Games known as the Olympic Truce resolution.

2. What’s the IOC’s mission?

The IOC has three main roles. The global nonprofit says “its job is to encourage the promotion of Olympic values, to ensure the regular celebration of the Olympic Games and its legacy and to support all the organizations affiliated to the Olympic Movement.”

In the Olympic Charter, the IOC goes into more detail about its principles, articulating the seven fundamental principles of “Olympism.”

These include placing “sport at the service of the harmonious development of humankind, with a view to promoting a peaceful society concerned with the preservation of human dignity,” promoting the “practice of sport [as] a human right,” a commitment to political neutrality and shielding athletes from discrimination.

The IOC is also supposed to protect the ethics and integrity of the Olympic movement, prevent athlete abuse and harassment, and generally make competitions safe, fair, and accessible for all qualifying competitors.

3. How does the IOC get money, and where do those funds go?

About three-quarters of its funds come from the sale of the rights to broadcast the Olympic Games. It gets most of the rest through marketing deals. The IOC collected more than US $5 billion for the 2014 and 2016 Games, the most recent data it has made available.

Because the IOC operates as a nonprofit, its leaders do not manage this money as they might if it were a private company. Instead, the committee distributes 90% of its revenue to national Olympic committees, Olympic athletes, and other entities, reserving the rest of the money to cover operational expenses.

The IOC also provides half of the funds used by the World Anti-Doping Association, established in 1999 to research and monitor the use of prohibited medications and treatments by athletes. Governments provide the rest of the association’s funding.

Olympic athletes, especially those who compete on U.S. teams, get very low compensation for their participation in the Games, and they are limited in terms of their ability to earn money from marketing deals. Bach, although he is technically a volunteer, earns about $244,000 a year, and other IOC leaders are paid as well.

4. What are some of the controversies the IOC faces?

The IOC’s response, in 2014, to prove that the Russian government was sponsoring systematic doping of its athletes has led to widespread criticism for being too lenient and has sparked controversy ever since. To punish the Russian government, without sidelining all Russian athletes from the Games, the IOC permits them to compete as “Olympic Athletes from Russia” without allowing the use of the Russian flag or anthem.

In 2022, doping remained a problem. That became clear when belated test results showed Russian figure skater Kamila Valieva had used a banned heart medication several weeks before she competed in the Olympics. The IOC’s response to this news appeared to disappoint all sides.

A figure skater on the ice during the Beijing Winter Games, Kamila Valieva of Russia kept competing in Beijing after evidence that she had tested positive for a banned substance came to light.

Separately, the IOC has failed to stop corruption in the bidding process for hosting the Olympics, a longstanding problem most recently exposed with the 2016 Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro and the Olympic Games held in Tokyo five years later.

Human rights groups have expressed outrage over the IOC’s decisions that allowed China to host the Olympic Games in 2008 and 2022.

China faces widespread accusations, including from the U.S. government, that it oppresses Uyghurs in China’s western Xinjiang region. This abuse is increasingly considered to constitute genocide.

Many athletes and other people object to China’s repression of the Tibetan people. China has also drawn widespread criticism for cracking down on free speech in Hong Kong.

The United States and several other countries cited these concerns in announcing a diplomatic boycott of the 2022 Beijing Olympics.

Interestingly, the committee states that “at all times, the IOC recognizes and upholds human rights” on its website.

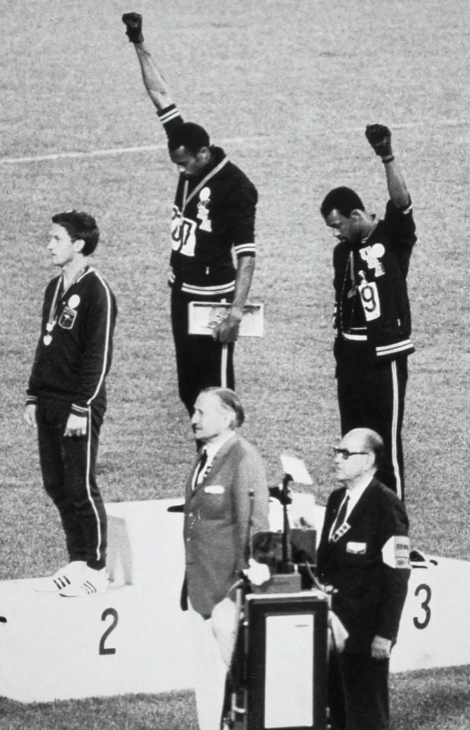

The IOC has also come under fire for its Rule 50.

Originally adopted in 1975 as Rule 55, it now states that “no kind of demonstration or political, religious or racial propaganda is permitted in any Olympic sites, venues or other areas.” This is the rationale for why the IOC bars athletes from engaging in protests while they compete or during medal ceremonies.

Time and again the IOC has relied on Rule 50 to justify its commitment to what it calls “political neutrality” as a fundamental principle of Olympism – even when that commitment has contradicted one or more aspects of its mission.

5. Is the IOC neutral and apolitical?

Well, it depends on whom you ask.

“The position of the IOC must be, given the political neutrality, that we are not commenting on political issues,” Bach said when asked about the abuse of Uyghurs by China’s government at the outset of the Beijing Winter Games. “Because otherwise, if we are taking a political standpoint, and we are getting in the middle of tensions and disputes and confrontations between political powers, then we are putting the Olympics at risk.”

In 2020, likewise, Bach wrote that the Olympics “can set an example for a world where everyone respects the same rules and one another.”

Human rights experts and activists around the world, however, have called the IOC’s position to be apolitical a myth and urged the committee to take a stronger stance on human rights abuses.

Shortly before the Tokyo Games began, in the summer of 2021, more than 150 experts on sports, human rights, and social justice – including both of us – published an open letter. In it, we called on the IOC to demonstrate a stronger commitment to human rights and social justice.

“Neutrality is never neutral,” we argued. “As a reflection of society at large, sport is not immune to the social ills that have created global inequities. … Staying neutral means staying silent, and staying silent means supporting ongoing injustice.”