Editor’s Note: This article about Doug Glanville, a former MLB player and Neag School faculty member, originally appeared in the UConn Magazine.

Doug Glanville has no right to be this good at this many things.

When Neag School of Education professor Doug Glanville cleaned out his garage during a recent family move, he unearthed some unusual stuff. Interspersed among the old grill equipment and lawn chairs were a dozen baseball bats, signed by Derek Jeter and other MLB stars, and beneath them a pair of Nike spikes that once belonged to Michael Jordan, during his year of professional baseball.

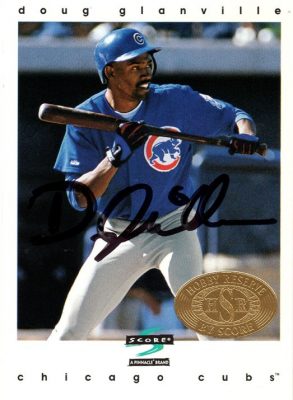

These items were not the treasure trove of a fan or collector, but rather the personal scrapbook of a man with the unlikeliest of backgrounds for a professor: Major League Baseball. As an outfielder with the Cubs, Phillies, and Rangers, Glanville spent a successful nine years on the field where it happens — in 1999 he batted .325 while stealing 34 bases. He showed me a panoramic photo of jam-packed Enron Field in Houston, on its inaugural night back in 2000, pointing to a tiny figure at the plate. “That’s me, leadoff guy. I got the first hit and first stolen base in the history of Enron Field.”

Glanville’s post-baseball career has brought him to teach at the Neag School as a professor from practice. Where many retired baseball players at his age — he turned 50 last year — would be pitching batting practice, this fall the former pro is pitching questions and essay assignments at students in his popular class, “Sport in Society.” The course, required for sports management majors, takes on the intractable nature of social and racial injustice: What are the underpinnings of justice? What are the obstacles in the U.S. to achieving it? How might sports provide both model and means?

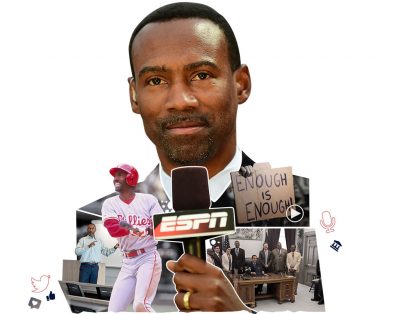

The origins of “Sport in Society” trace to the years after Glanville’s 2005 retirement, when he worked for ESPN and found himself pondering issues beyond the scope of a play-by-play announcer. “It was a convergence of my passions with what I was learning in media work,” he recalls. “At some point I just started jotting down ideas about sports and social justice.” He approached Major League Baseball and offered himself as a resource for players looking to engage with social issues. The league showed interest but made no commitment. Eventually Glanville decided to turn his notes into a course.

The class, he explains, situates students at the intersection of sport, society, and activism. “We look at how athletes and sports engage on social justice subjects via all sorts of pathways — legislative, political, legal, media. We go through these elements and try to come out in a forward-thinking way.”

Texts range from Eric Liu’s “You’re More Powerful Than You Think” to Floyd Abrams’ “The Soul of the First Amendment” and Heather McGhee’s “The Sum of Us.” Glanville incorporates articles by such activist athletes and former Huskies as Sue Bird ’02 (CLAS), Maya Moore ’11 (CLAS), and Breanna Stewart ’16 (CLAS). He added Renee Montgomery ’09 (CLAS) to that list this semester. Guest speakers have included baseball player Adam Jones and former players’ union chief Donald Fehr.

The course takes up hot-button issues that have only become hotter since the killing of George Floyd. But Glanville is no Johnny-come-lately to activism and the struggle for change. Indeed he has been working toward it since he left baseball, fashioning a way to draw the personal and the political together, examining his own life experiences within the larger American context.

Like the canny base runner he once was, Glanville got the jump on the zeitgeist, his eyes fixed on a sense of where we are headed, and what we need.

No Human Shall Possess Two Different Champion Skillsets

A universal rule of thumb for the distribution of talents holds that no human shall possess two different champion skillsets. A Michelin-starred chef should not do research in quantum physics. A marquee movie star should not win a Pulitzer Prize for journalism.

And Doug Glanville should not be Doug Glanville, a distinguished Major League Baseball player who also possesses the writing chops to perform at the highest literary level. Over the past 15 years, the former Phillie has written a series of op-eds in The New York Times, essays graced with candor, wisdom, and wit. In 2010 he published “The Game From Where I Stand,” an absorbing chronicle of his life as a professional athlete. The memoir won rave reviews; acclaimed journalist and “Friday Night Lights” author Buzz Bissinger called it “a book of uncommon grace and elegance … filled with insight and a certain kind of poetry.”

Soft spoken and thoughtful, Glanville carries his excellence lightly. “You’d never know that Doug was a Major League Baseball player,” says Jason Irizarry, Neag School dean. “He does not wear his resume on his sleeve.”

Glanville credits his late father, a Trinidadian educator who emigrated to the U.S. and became a psychiatrist, and his mother, a math teacher, with giving him lessons in perspective. He enjoys recalling his father’s skeptical comment upon seeing the tinted-window Lexus his son had bought with his baseball wealth (“Looks like a drug dealer’s car”). And late in his career, when Glanville was tempted to boost declining physical prowess with performance-enhancing drugs — this was the height of MLB’s steroid era — it was his mother who warned him of the cost in hollowed-out self-respect. “My mom reminded me of the beauty of knowing that what you gave of yourself was authentic,” Glanville says. “Her attitude was, Are you going to sell your soul? For what? Money? Fame?”

He traces his optimism about diversity to his hometown of Teaneck, New Jersey, which in the 1960s voluntarily desegregated its schools. Glanville’s middle school lunchroom resembled the United Nations, he says. “It was a beautiful tapestry of people. That’s how I grew up.” In Teaneck he experienced daily interactions across race, class, and ethnic lines. What are now called “uncomfortable conversations” were routine. So was interracial solidarity. He told me about an incident during high school, when Teaneck’s baseball team played in a neighboring town and a close game turned on a contested call.

“Keep in mind, Teaneck was the diversity, and the surrounding towns didn’t like us a lot.” Heckling led to sharp words and after the game, a white fan hurled racial slurs, then tried to knock down a Black Teaneck player as the team exited the field.

Decades later, Glanville recalls the incident as a defining moment in his life. “Basically we almost got assaulted by a mob of white guys in suits. But we weren’t just a group of Black players who were being attacked. We were a diverse group of people. We knew that what had happened was wrong. We knew we were going to have to fight this together, and we knew we were stronger together. It’s like Heather McGhee says in “The Sum of Us,” it’s not Black versus white or white versus Black, it’s all of us against racism, right? Racism hurts all of us.

Shoveling While Black

His own life has served up the frequent slights that a Black person in America experiences. For most Americans of color, these incidents pass without garnering attention, but Glanville has the personal and professional “bandwidth” — a favorite word of his — to draw a light of publicity to them. Two racial incidents in the mid-2010s reveal his way of doing this. In a 2014 article in The Atlantic, “I Was Racially Profiled in My Own Driveway,” the former major-leaguer describes shoveling snow one morning outside his spacious home in Hartford’s West End, one street over from the West Hartford line, when a West Hartford police officer approached and asked, “So, you’re trying to make a few extra bucks, shoveling people’s driveways?” When Glanville explained he was shoveling his own walk, in front of his own house, the officer abruptly left.

“My biggest challenge as a father will be to help my kids navigate a world where being Black is both a source of pride and a reason for caution.”

Glanville subsequently was told by police that a Black man had broken a West Hartford ordinance prohibiting door-to-door solicitation, and the officer pursued the complaint across the town line to Glanville’s street. The ensuing encounter spawned the phrase “Shoveling While Black,” coined by Glanville’s wife, Tiffany, in an email to their neighbor, state representative Matt Ritter, it reflected the guilty-until-proven-innocent stigma that all too often afflicts Black Americans in their dealings with law enforcement.

“The shoveling incident,” Glanville wrote, “was a painful reminder of something I’ve always known: My biggest challenge as a father will be to help my kids navigate a world where being Black is both a source of pride and a reason for caution.”

The second incident, a year later, spawned another Atlantic article, “Why I Still Get Shunned by Taxi Drivers,” in which Glanville related his experience one night at Los Angeles International Airport (LAX), where he arrived with a white ESPN colleague and hailed a cab. The cab driver at first saw only the white colleague. When he noticed Glanville, he declined to take the two, shouting at Glanville repeatedly to take a bus instead.

In 2017, I heard Glanville lecture about this incident at the University of St. Joseph, an hour-long talk titled “Responding to Injustice in Ways that Work.” He introduced “a case study” of “a business traveler” arriving at LAX — withholding the fact that he was that traveler. Projecting LAX statistics on a screen — 81 million passengers and 6 million taxi trips a year — he told the story of the interaction that night at the airport, right through to the cabbie’s refusal of service. Hailing a cab, Glanville reminded his audience, is a simple transaction, or at least should be. Then, via a slide, he revealed the identity of the traveling duo. He smiled, ruefully acknowledging the racial aspect of the situation. “So now we have a problem, right?”

His approach was low-key and reassuring, like a doctor calmly relating a diagnosis and formulating a treatment plan. The treatment plan for LAX required action that Glanville confessed he’d been reluctant to undertake. “It’s 1 a.m., you just want to say ‘Forget it’ and get to sleep,” he recalled. But when a woman working near the taxi stand approached and told him he was the third Black man to be refused service that night, he knew he had to act. His privileged status as a media professional entailed responsibility, he told his audience. “I’m with ESPN, I have visibility and access, I can do something about this.”

“Yes, you need people marching in the streets, calling out injustice, going on CNN. But you also need people in the courtroom, in the policy room — people doing the slow work, the non-tweet-able work. Playing the long game.”

— Doug Glanville, Neag School faculty member

The rest of the lecture detailed the methodical steps Glanville took over the ensuing weeks and months. Digging into relevant civil rights law and taxi management agreements. Investigating procedures for handling complaints. Coordinating with LAX in the formation of a sting operation, with Black undercover officers in plainclothes hailing taxis (an “astronomical and shocking” 6 out of 25 were refused service, Glanville related). And ultimately working with the LA City Council to create training for all airport cab drivers, set “zero tolerance” for racial discrimination, and devise a new complaint system.

In the Q&A, a Black professor marveled at his forbearance. “I don’t think anyone would blame you if you got very upset with that cab driver. What enables you to be so resilient in the face of such an offensive act?” Glanville answered with typical thoughtfulness. “I was very upset. But I didn’t see what I would gain by getting in his face. Say I get mad and take a selfie, make a lot of noise. Maybe I blow up this guy’s career. That probably works for my own gratification, for revenge. But for me there has always been a moment when I realized that there’s an opportunity to benefit a lot more people than just me.”

Glanville’s Mission at UConn and Beyond

The LAX lecture highlighted two key facets of Glanville’s M.O. as a teacher, fundamentals that guide his mission at UConn and beyond. One is his gift for presenting personal issues dispassionately, even as he makes political ideas highly personal. “Doug has a terrific ability to take complex experiences, profound experiences, and discuss them in a way that is both academically rigorous and yet totally accessible,” says Irizarry. “Students respond to that in a big way.”

The second is his emphasis on constructive action — and on the patience it requires. “That can be challenging for this generation,” Glanville tells me. “Their temptation is to quickly tweet out outrage. Boom boom boom, 280 characters, and it’s out there, right?” He pauses. “But then it’s over. All of a sudden, the message is gone.” Raising the temperature in a confrontational way can be gratifying emotionally, but the effort to create change requires a deeper dive. “Yes, you need people marching in the streets, calling out injustice, going on CNN. But you also need people in the courtroom, in the policy room — people doing the slow work, the non-tweetable work. Playing the long game.”

Take the effort to reform policing. Glanville supports it wholeheartedly, but views cooperation, rather than confrontation, as the key. “I believe law enforcement’s important, so if I’m trying to create change, I need their buy-in. In Connecticut, for instance, it’s the POST Council — Police Officer Standards and Training — that trains police officers and sets curricula and standards. A lot of people haven’t even heard of it, right?”

Take the effort to reform policing. Glanville supports it wholeheartedly, but views cooperation, rather than confrontation, as the key. “I believe law enforcement’s important, so if I’m trying to create change, I need their buy-in. In Connecticut, for instance, it’s the POST Council — Police Officer Standards and Training — that trains police officers and sets curricula and standards. A lot of people haven’t even heard of it, right?”

Glanville joined the council four years ago, after the Shoveling While Black incident. As he readily points out, the group is hardly a populist arrangement. “But we do a lot of work. We’ve passed legislation governing use of force. We have hot-pursuit laws. We get stuff done.” And getting stuff done, he teaches his students, requires persistence. “When you feel racism, you want it to change, and you want that to happen now. I get that. But you have to embrace the slow work. It’s not sexy, but it’s what actually lets you make change that sustains itself. The long game is what sticks.”

Glanville practices what he preaches. Not satisfied with merely writing about Shoveling While Black, he took action, collaborating with Rep. Ritter to craft a bill, signed into law by Gov. Malloy in 2015, placing limits on law enforcement’s pursuit across town lines for minor infractions. Years later, Ritter is still talking about it. “It amazed me that a former major league player was willing to do the hard work of meeting with legislators and staff. It showed both humility and a terrific commitment. This bill never would have become law without Doug.”

If Glanville ever runs for office, Ritter says with a laugh, he’ll volunteer to run his campaign. And indeed, if you spend an evening with the former major leaguer, you’re likely to leave thinking that he’d be an excellent mayor.

Making a Stirring Plea for Social Change

In the aftermath of the George Floyd killing, Glanville recorded an impassioned commentary on ESPN, “Enough,” making a stirring plea for social change. Noting that the 8 minutes and 20 seconds it takes for sunlight to reach the Earth approximates the time it took for Floyd to die under an officer’s knee.

He drew a metaphor in which, following the darkness of despair, “the sun rose again, giving us another opportunity to be enlightened — to help us see George Floyd as all of us, and not just ‘one of them’… [and to] respond, and make his death be our light.”

In Glanville’s brand of social activism, this poetry is channeled through pragmatism; he offers inspiration, then counsels perspiration. It’s not surprising that his “number one text” for “Sport in Society” is called “Systems Thinking for Social Change.” The first Black Ivy League grad to play Major League Baseball, Glanville majored in engineering at the University of Pennsylvania, and there’s a strong element of engineering in the way he views social problems — and how he goes about solving them. “I studied engineering because I loved science, but I always wanted to apply it,” he says. “I wanted to understand not just how to build something, but how it will impact the world.”

The activism of the engineer includes understanding that racism is a complicated system, from which there is no easy way out. But systems, as Glanville teaches his UConn students, can be improved. “In engineering you begin with a system as it is,” he says. “Policing, housing, whatever: you study the system, its nuances and intricacies, and you measure how it performs. Then you project out for what the system will be in the future — whether it declines or deteriorates or just amplifies the current reality. Where the beauty and design and humanity come in is in trying to imagine the system as it should be. That is the destination, that aspirational space. Your whole work as an engineer is to bend that curve and that arc — from as it will be, to as it should be.”

The research on the efficacy of grade retention suggests that it is not a particularly effective intervention, although there is evidence of some short-term gains. For example, a number of studies find students typically improve during the year they repeat (Frey, 2005). Other research suggests positive impacts on self-concept as well (Lamote et al., 2014). This may be expected, however, given that the content the students are receiving is similar if not identical to the year prior; these gains may simply be limited to the “head start” repeating students have in comparison to peers learning content for the first time.

The research on the efficacy of grade retention suggests that it is not a particularly effective intervention, although there is evidence of some short-term gains. For example, a number of studies find students typically improve during the year they repeat (Frey, 2005). Other research suggests positive impacts on self-concept as well (Lamote et al., 2014). This may be expected, however, given that the content the students are receiving is similar if not identical to the year prior; these gains may simply be limited to the “head start” repeating students have in comparison to peers learning content for the first time.