Teachers of Connecticut (Neag School alumna Symone James is featured)

Focus on Finances to Promote Doctoral Student Diversity

Brookings (A study by H. Kenny Nienhusser and Milagros Castillo-Montoya is mentioned in an article co-authored by former Neag School faculty member Shaun Dougherty)

Does Creativity Help Brain Health

Prevention Magazine (James Kaufman is quoted about what creativity really means)

The Enduring Human Rights Legacy of Christopher Dodd

UConn Today (Glenn Mitoma is quoted about the Dodd Center for Human Rights dedication ceremony)

How Reparations Can Be Paid Through School Finance Reform

Editor’s Note: Co-written by Preston Green and Bruce Baker from Rutgers University, this article on addressing racial inequalities in education, originally appeared in The Conversation.

Schools in predominantly Black communities receive less funding, even though Black homeowners pay higher tax rates.

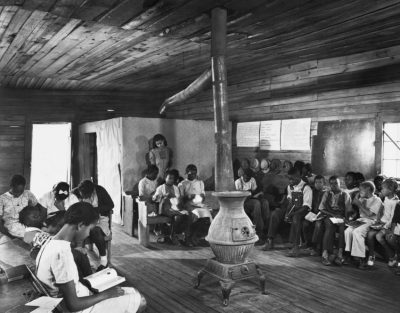

White public schools have always gotten more money than Black public schools. These funding disparities go back to the so-called “separate but equal” era – which was enshrined into the nation’s laws by the Supreme Court’s 1896 decision in Plessy v. Ferguson.

The disparities have persisted even after Brown v. Board of Education, the landmark 1954 Supreme Court decision that ordered the desegregation of America’s public schools.

Since Black schools get less funding even though Black homeowners pay higher property taxes than their white counterparts, we think reparations are due – and they can be paid by reforming the ways Black homeowners are taxed and schools in Black communities are funded.

We make this argument as school finance and education law scholars who have studied racial inequality in education for decades. We propose a four-part reparations plan to address racial inequalities in education. The plan deals with: 1) local property taxes, 2) school revenues, 3) targeting funding to close gaps in student outcomes, and 4) federal monitoring.

1. Tax Rebates for Black Homeowners

A big reason for racial funding disparities is housing segregation. This separation has led to vast differences in housing values and wealth that families have been able to accumulate. This in turn affects how much funding can be raised through property taxes for local public schools.

In Connecticut, for example, Black-owned homes are valued on average at about $250,000, versus over $420,000 for white-owned homes. Even for homes in the same metro areas within Connecticut with the same number of bedrooms, the difference is $173,000.

A big reason for racial funding disparities is housing segregation.

Since Black home values overall are lower, higher tax rates are often adopted to generate more local tax revenue. This comes in the form of what we refer to as a “Black Tax.” In Connecticut, the average Black homeowner pays a Black Tax of just over 0.6% in higher property taxes. On a $250,000 home, that amounts to $1,575 per year. But even with higher tax rates, Black communities do not raise the same amount of property tax revenue to fund public schools as white communities in the same state or metropolitan area. Tax rates required to fully close these gaps would simply be too high. In a 2021 article, we documented similar disparities in other states, including Maryland and Virginia.

We recommend direct rebates to Black homeowners in previously redlined or otherwise segregated communities in the amount calculated to cover the Black Tax. For example, the Black Tax in Bridgeport, Connecticut is just over 0.5%. For a home valued at $340,000, the annual rebate amount would be just over $1,800. These rebates would put money in the hands of Black homeowners, who would then have the option to either spend more on their local public schools or increase their personal savings. Either way, we believe they are owed this compensation, including possible cumulative compensation for past overpayment.

2. Closing Racial Gaps in School District Revenues

State general aid programs, which are intended to make sure all schools get equitable funding, routinely fall short.

In Connecticut, the average state general aid per Black child is $2,756 more than the average state general aid per white child. This is because districts serving Black children tend to have less of their own taxable wealth. That is, districts serving more Black children do receive more state general aid than districts serving more white children, but not enough to close the gap $4,295 in local revenue raised. We calculated that the remaining gap is $1,574 per pupil. Additional state aid to school districts in Black communities could close this gap.

3. Change How Race Factors into School Aid Formulas

Money matters for improving schools and improving student outcomes – from test scores to graduation rates and college attendance. School finance reforms have proved especially beneficial to Black students. Research is increasingly clear in this regard. Equitable and adequate financing of public school systems is a necessary condition for ensuring children equal opportunity to succeed.

Equitable and adequate financing of public school systems is a necessary condition for ensuring children equal opportunity to succeed.

State school finance formulas include weights – or cost adjustments – for things like how many children live in poverty or how many children have disabilities. The idea is that such children require more money to educate. The evidence and related studies show that, because of governmental policies that created racial isolation and the economic disadvantage that accompanies it, school and district racial composition is an important factor to include in state school finance formulas. But no state currently does this.

4. Eliminate Racism in School Finance Formulas

Some state aid programs exacerbate racial disparities, and worse, some are built on the systemic racist policies that created them.

Kansas, like many states, imposes strict revenue limits, or caps, on revenue that can be raised locally in order to maintain equity. But a 2005 provision added to their school funding formula raised the cap for 16 districts with higher average housing values, based on the claim that those districts needed to pay teachers more to live in their districts. But this specific provision almost uniformly applied to predominantly white districts where most neighborhoods had racially restrictive covenants in earlier decades.

Some state aid programs exacerbate racial disparities, and worse, some are built on the systemic racist policies that created them.

The provision excluded neighboring districts where homes had been devalued by redlining because they were inhabited by Black residents. These neighboring districts also presently use their maximum taxing authority.

We recommend federal audits of state school finance systems to identify features of those systems that exacerbate racial disparities and may in fact be built on systemic racial discrimination. Since states have thus far been unwilling to lead these initiatives themselves, we believe they need federal encouragement.

The funding adjustment on high-priced houses in Kansas provides one example, but there are others, including state aid programs designed to reduce local property tax rates in affluent suburban communities.

UConn Game Designers Win Big in Connecticut

UConn Digital Media & Design (Neag School faculty and students are mentioned)

The Long Game

UConn Magazine (Neag School faculty member and former MLB player Doug Glanville is profiled)

2021 40 Under Forty: Kailee Ostroski

Hartford Business Journal (Neag School alumna Kailee Ostroski is featured)

Dr. Joseph S. Renzulli, 2021 Lifetime Achievement Award winner

Mensa Foundation (Joseph Renzulli is featured about receiving the Mensa Foundation’s Lifetime Achievement Award)

New Research Study to Investigate — and Address — Teacher Stress

Even prior to the pandemic, stress and poor mental well-being stood out as the main factor driving school teachers from the classroom — not to mention the No. 1 reason for the nation’s current teacher shortage, according to Neag School Professor Lisa Sanetti.

When it comes to teacher stress, COVID-19 has only caused further damage. In surveys done during the pandemic, Sanetti says, 60% of teachers nationwide reported enjoying their job less, and a quarter of them indicated that they were “just getting by” or “having difficulty getting by” financially.

“Decades of ignoring teachers’ poor mental well-being combined with the stressors of COVID-19 has significant short- and long-term threats to the teacher supply in the U.S.,” Sanetti says. “The implications for students, families, districts, and our nation could be dire.”

Thanks to newly renewed federal funding for a Total Worker Health® Center of Excellence — a collaborative program between UConn Health, UConn Storrs, and the University of Massachusetts-Lowell — Sanetti, co-PI and UConn Health Associate Professor Jennifer Cavallari, UConn Health Assistant Professor Alicia Dugan, and their colleagues will be carrying out a five-year study specifically focused on improving the mental well-being of school teachers. The long-term goal is to boost retention of teachers in the field.

“Decades of ignoring teachers’ poor mental well-being combined with the stressors of COVID-19 has significant short- and long-term threats to the teacher supply in the U.S.”

— Professor Lisa Sanetti

The funding, secured by Associate Professor of Medicine William S. Shaw, chief of UConn’s Division of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, comes from the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). NIOSH funds 10 different Total Worker Health Centers of Excellence nationwide.

The Center for the Promotion of Health in the New England Workplace (CPH-NEW) is a Center based at UConn and UMass-Lowell. Its research goal, per the Center’s website, is “to evaluate the feasibility, effectiveness, and economic benefits of integrating occupational health and safety with health promotion interventions to improve employee health.”

Partnering With School Districts

One of three new CPH-NEW projects, the Total Teacher Health research study will involve anonymously surveying more than 1,600 teachers in select school districts across the country and conducting focus groups to identify the factors affecting teachers’ mental health and well-being.

Sanetti, an expert in school-based mental health, is part of an interdisciplinary team with experts in industrial/organizational psychology and occupational epidemiology, which will look to partner with three Connecticut school districts on implementing CPH-NEW’s Healthy Workplace Participatory Program (HWPP), a research-based approach to improving workplace health and well-being.

Working closely with designated groups of schoolteachers and administrators at two elementary schools within each of these three school districts, the researchers will guide teachers in identifying their most intense stressors, their causes, and possible interventions.

The ultimate goal will be to implement interventions for these teachers throughout the school year to reduce their stressors and improve mental well-being. Each intervention will be designed to address specific factors that the researchers have uncovered as negatively influencing teachers’ mental health. The HWPP, the researchers note, prioritizes changes in the way work is done over personal behavior changes.

The following year, Sanetti says, the team will not only re-engage in this process to address additional factors, but will also look to ramp up “capacity within each school to continue building their school as a healthy workplace” going forward.

“CPH-NEW has demonstrated the success of the HWPP in providing supervisors and workers with the processes and skills to implement workplace changes that improve worker well-being,” Cavallari says. “We look forward to working with teachers.”

Three schools in two districts in Connecticut were involved in piloting the HWPP. Teachers in each school identified unique stressors, and the HWPP process led to site-specific interventions that began reducing stressors and improving working conditions.

“We are indebted to the teachers and principals who participated in the pilot studies. They provided critical information about how the HWPP can be adapted to fit within school routines and confirmed that one-size-fits-all approaches aren’t likely to work,” Sanetti says. “We hope to have a better understanding of teacher mental well-being and the factors influencing teacher stress, and how to feasibly reduce them.”

Adapting the implementing the HWPP will, the researchers hope, provide a vital avenue for improving teachers’ work-life balance, reducing their level of burnout, and positively engaging them in their work.

To learn more about being a Total Teacher Health School District Partner, contact Lisa Sanetti in the Neag School’s Department of Educational Psychology.