When Neag School of Education professor emeritus Vincent Rogers’ daughter and her husband — both schoolteachers — received a $5,000 grant to study educational techniques in New Zealand, Rogers himself was inspired to add to his family’s existing Neag School fund with something similar for teachers in Connecticut.

Rogers recently announced a planned bequest to the Neag School, designating a legacy gift of $125,000 to expand the Rogers Educational Innovation Fund in support of innovative projects carried out by teachers in Connecticut. Through his gift, elementary and middle-school teachers across the state will be able to apply annually for a $5,000 gift for use in the classroom.

Rogers’ daughter and son-in-law, teachers at the Pine Point School in Stonington, Conn., used the grant they had received to visit schools in New Zealand, networking with educators and learning techniques that would, in turn, enrich the school where they teach.

Rogers, now 90, recalls how the grant impacted them and, ultimately, inspired him personally to expand a Neag School award he and his wife previously established, that will now, he says, “be an open-ended initiative for the teacher … to come up with a really creative idea that would help them, the school, and the children.”

Giving Back to Teachers

Rogers and his now late wife, Chris, also a longtime educator, previously established a fund at the Neag School through which elementary school teachers in Mansfield, Conn., could apply annually for a $1,000 grant to enrich their classrooms. Over the years, eight grants were made to local schools.

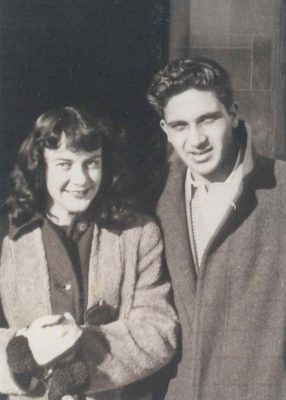

Chris Rogers, who passed away in 1999 from complications after a 30-year battle with multiple sclerosis, inspired many children over her three-decade career, but did not let her disability keep her from making a difference, says her husband, who calls her “the greatest teacher the world ever saw.”

Vincent Rogers has announced a planned bequest to the Neag School, designating a legacy gift of $125,000 to expand the Rogers Educational Innovation Fund in support of innovative projects carried out by teachers in Connecticut.

Rogers’ additional gift will be open to elementary and middle-school teachers across the state of Connecticut to “support research and programs for the collaborative work of classroom teachers and the Neag School of Education,” and award recipients will have the freedom to use the award in any way they see fit. Rogers, who spent four decades teaching and writing about education techniques, led the Neag School’s Department of Curriculum and Instruction and served on its faculty, retiring in 1990.

A History of Inspiration

A third-generation Italian growing up in New York, N.Y., Rogers had not traveled much beyond the city during his youth. But when a high school friend who went on to Cornell University invited Rogers to see his college campus, Rogers found himself inspired.

“That visit changed everything,” he says. “The sheer beauty of the campus, the academic atmosphere, the intellectual atmosphere … Those guys walked across the campus at 10 in the morning with a little folder under their arm, giving lectures.” He recalls thinking: “I’m interested in that job. How do you get that job?”

Accepted at Cornell as a history major, Rogers was drafted in his second year by the U.S. Army and originally slated to serve in combat overseas. But Rogers, a jazz musician during his high school days, was then reassigned to play trumpet in the West Point Military Academy band. After playing for West Point for nine months and completing his three-month basic training, Rogers qualified for the G.I. Bill, which allowed him to return to Cornell with his education costs covered.

Cornell provided more than a degree for Rogers; he also met his wife, Chris, there. Following college, they both taught in the Westhampton Beach, Long Island, school system for several years before Rogers was made school principal at James Port School on Long Island. It was a role he believes he was given not due to his natural leadership ability, but because he was a man.

“I was a good teacher, but hadn’t been there that long,” he says. “Most of the faculty were women, and Chris would have made a better principal.”

While leading the school in Long Island, Rogers took graduate extension courses through Syracuse University. One professor took a liking to Rogers and suggested he go to Syracuse for a graduate fellowship program.

“Here was my way to get what I wanted: to be a college professor,” he says.

Against his parents’ wishes, the Rogers family went to Syracuse. “My family [thought] that I was crazy to leave a job like a principalship. Back in the 1940s, you didn’t leave good, steady jobs,” he says.

Eventually earning a doctorate in history in 1949, Rogers was hired as an assistant professor at Syracuse — fulfilling his dream and starting his long-awaited career as an academic.

Open Education

Rogers taught at Syracuse for a number of years and was then recruited to the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. Through colleagues, he later connected with faculty at Johns Hopkins University, which had a center for international studies in Bologna, Italy. There, he participated in its American teachers abroad program, a six-week opportunity for Rogers and fellow faculty from history, economics, sociology, and education, which turned into two summers abroad for Rogers and his family.

University of Minnesota came calling next, where they spent the next five “incredible” years. During this time, the Fulbright Program came into the picture for Rogers when an administrator of education from England, who had been following Rogers’ published works, suggested he apply for a Fulbright.

“He visited my classrooms, and we had long conversations about education in general,” recalls Rogers. “He seemed to think I was just what they needed.”

Rogers’ Fulbright research targeted child-centered learning in British schools, which focused attention on children doing and being active in the classroom, versus being lectured to. His work led to the publication of a book called The Social Education of British Children (1968, Heinemann Publications). The Fulbright ended, and he returned to University of Minnesota. Through his time, he continued publishing about child-centered education, also known as open education.

This work sparked the attention of many institutions, including that of the University of Connecticut, which sought an individual to lead the nation in developing child-centered education in the U.S. as chairman of the curriculum and instruction department in the School of Education. Rogers led the department for five years and continued to publish and travel the world, speaking and writing about child-centered education until returning to a faculty role and continuing his research.

“Everyone was interested in open education, and I was giving lectures everywhere,” Rogers says. “I’m a firm believer that if you want to improve and get new ideas, it’s best not just to read about them, but to go and see it happen.”

“Vin was absolutely one of the very best department heads I ever knew,” says Neag School professor emeritus Gil Dyrli. “He led by example through conducting groundbreaking research, publishing significant books and articles, and presenting keynote addresses at major professional conferences.”

“He was a world leader in international education and the education movement known as ‘open education,’ and wrote the definitive book in the field,” Dyrli adds. “As I travelled the country throughout my career, representing UConn and doing staff development, a common question was ‘Do you work with Vin Rogers?’”

Innovation Back Home

In Connecticut, Rogers followed through on his innovative work. He connected with a fellow School of Education faculty member, the late A.J. Pappanikou, whose focus was on special education, with whom he partnered to ensure that future educators were getting hands-on experience in urban school settings.

Together, they coordinated about 20 UConn students to do their student teaching in New Haven, Conn., where, Rogers says, students had an opportunity to get a view of schools beyond suburbia — a rare and innovative practice at the time.

“His many students have gone on to important positions at state, national, and international levels in public and private education,” says Dyrli. “His original contributions and seminal ideas continue to be worth exploring, and thanks to the internet and online resources, they are more accessible than ever.”

With his newly announced bequest to the Neag School, Rogers will now be passing that spirit of innovation to yet another generation of students, giving teachers in Connecticut the opportunity to enact innovative projects of their own in elementary and middle-school classrooms across the state.

Learn more about the Rogers Educational Innovation Fund — and apply for the grant — at rogersfund.uconn.edu. Consider a gift in a support of the Neag School.