In this new series, the Neag School is catching up with students, alumni, faculty, and others throughout the year to give you a glimpse into their Neag School experience and their current career, research, or community activities.

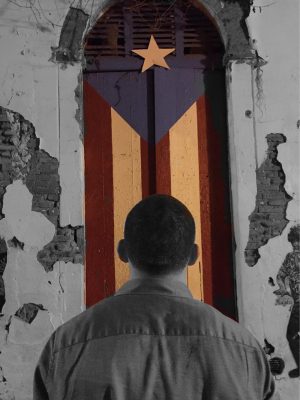

Two Neag School alumni, Gabe Castro ’14 (ED), ’15 MA, and Jill Linares ’14 (CLAS), ’15 MA, spent this past academic year — their first year of teaching — at Guamani Private School in Guayama, Puerto Rico. There, Castro teaches seventh-grade pre-algebra; ninth-grade and 10th-grade geometry; 11th-grade algebra II; and 12th-grade college math; Linares teaches seventh- and eighth-grade English. They now both remain in Puerto Rico as they start in on their second year of teaching. Both Castro and Linares are graduates of the Neag School’s Integrated Bachelor’s/Master’s program.

1. Why did you decide to work in Puerto Rico?

GC: During my time at UConn, I wanted to study abroad, but I switched into the education program late. The desire to study abroad transformed into wanting to teach abroad. Although originally I wanted to move to a Spanish-speaking country, Puerto Rico was not on my list of schools I was looking at. However, during the interview process I was able to connect with both the director and principal of the high school there. They told me I would be teaching the age and topics I desired and even offered me housing. For me, making the move to Puerto Rico would be everything I was looking for as an educator.

JL: I wanted to become fluent in Spanish. I also wanted a change of pace from growing up in New York City, and I must be honest – the weather certainly was an appeal.

2. How was the transition to teaching in Puerto Rico, and how were you prepared?

GC: As a first-year teacher, I wasn’t sure what to expect or how to prepare. From my student teaching experience and the master’s internship at the Neag School, I am used to having a set curriculum to follow. At the private school in Puerto Rico, I am free to choose how I want to structure my curriculum. In addition, I had never taught in a block schedule before, so having students for 90 minutes every other day was an adjustment.

JL: I don’t think the foreign aspect was any more daunting than the first year of teaching aspect.

3. What was it like during your first month of teaching?

GC: The first month of my first-year teaching was nothing like I expected. I thought I was going to step in front of my classes and groove, but that’s not what happened. Truthfully, I struggled to keep organized with four preps and setting up my classroom routines. Seeing students every other day was not what I was used to. So if I had to talk to a student for any particular reason, I needed to make sure to write it down for the next day. After the first month, I finally started getting in my rhythm and had my routine in and out of the classroom.

JL: I made sure to go over the procedures of my classroom thoroughly in order to get students familiar with what our class would be like. We played icebreaker games and students all wrote me a letter as a part of their first assignment, so I could get to know them and their families. I wrote all 98 of my students a personal letter back, which took a lot of time, but was so worth it. I will most certainly be using that assignment again this upcoming year.

“The first month of my first-year teaching was nothing like I expected. I thought I was going to step in front of my classes and groove, but that’s not what happened.” Gabe Castro ’14 (ED), ’15 MA

4. Were you homesick, and how did you stay in touch with family/friends back in the U.S.?

GC: Having lived away from home for five years, three of which I had my own apartment, I am used to being away from my family and friends. However, knowing I had to fly to be back home was an adjustment. Thankfully with technology, I am able to Skype and FaceTime with friends and family regularly.

JL: I didn’t really get homesick to be honest. I flew back home a couple weekends for family functions, and people came to visit me. It’s only a four-hour flight, which makes the travel to and from just a small bump in the road. FaceTime is a great way to “be there” when I can’t be there.

5. What were some of your favorite moments during the past year?

GC: Jill brought down [fellow alum] Justis Lopez ’14 (ED), ’15 MA to guest teach in one of her classes. I decided to piggyback off of Justis being in Puerto Rico to do my unit in math poetry. While he was in the area, he spoke to my group of seniors about his journey as a poet and what it has done for him. [The students’] poems were designed to target mathematics, the Castro Classroom Experience, and their time at Guamani School as a whole. To set the example, I wrote a poem for them that I read aloud after they had finished their finals.

JL: My favorite moments were when students would give me feedback on their end-of-semester reflections. I like to hear what students have to say, so their anonymous surveys help me to better address their needs for the future. It’s a great way to peek into their minds without them feeling uncomfortable about what they “should say.”

6. What challenges did you face, and how did you overcome them?

GC: Something trivial, but challenging for me was having my laptop snap apart during the first semester. Everyone always advises you to back up files on hard drives and on clouds, but it takes losing your files to realize how important that really is. Thankfully, I had only lost about a month and a half’s worth of lessons and ideas, but now I’ve learned my lesson: Always back up my files!

JL: Our school did not have a copy machine that teachers could use. In fact, we could only request to get copies if we had a test and, if approved, we only got one class set, no matter how many classes took that exam. This was a perplexing challenge in the beginning, but I learned how to use technology as a means or replacing paper almost completely.

7. What have you liked about working there?

GC: One of the things that I have liked the most is the school spirit these kids have. There are two major sport tournaments in each of the semesters: one volleyball and one basketball. The school sells T-shirts to raise money, but it is also a free entrance to the event. At each tournament, students are there in their shirts cheering each other on.

JL: I love how motivated the students are. They are absolutely brilliant and amaze me all the time. They are eager to learn and by being bilingual, they bring a whole new perspective with them to class every day.

8. Would you recommend others to teach abroad?

GC: I highly recommend teaching abroad. Although I never studied abroad, I can imagine this experience has surpassed what that would have been. You are embracing another culture, experiencing what their style of living is like, exploring new land, and establishing connections with people that will last a lifetime. For those interested, I encourage them to seek this opportunity.

JL: At this point in my life I think it is the best time — if ever — to teach abroad. I am not married; I don’t have any kids, and no permanent obligations to be anywhere. I don’t think teaching abroad is for everyone, but it has certainly positively impacted my life immensely. If a teacher who is “thinking about it” asked me for advice, I would tell him/her to do it! But I don’t think it would be good for those who aren’t interested in it. It’s the type of experience a person needs to decide on his/her own.

9. How did the Neag School prepare you for this experience?

GC: I think that it is tough to prepare teachers to teach in another country. That being said, the Neag School did an amazing job teaching me how to reach different styles of learners. Being aware that not every student is going to understand something the first time or the first way you teach it, but being able to change and adapt to your students’ needs is crucial.

JL: To be completely honest, I was terrified after undergrad once I finished my student teaching. I believe that I felt most prepared after my fifth year. My methods class with Wendy Glenn helped a lot, so did my Teaching Young Adult Literature class with Wendy. Leadership with Erica Fernandez was also an immense help and put me on track to get ahead with my lessons early on. Professors who gave me advice one-on-one helped prepare me in finding the right “fit” [were] David Moss, Mark Kohan, and Wendy.

10. How has your perspective on teaching in Puerto Rico changed your outlook on teaching?

GC: Society likes to put labels on types of people. If you are a certain race or ethnicity, you should or will normally behave a particular way. Although there are cultural norms teachers should be aware of, they should also seek to incorporate them in the classroom. When teachers share with students personal anecdotes about their lives, students reciprocate that. Not only are students learning the content, but also learning from each other.

JL: I like that I am often put in a language-learner’s position. I can empathize with my students who are struggling with learning the language or even grasping a concept. When speaking in Spanish, I often feel stuck — like I can’t articulate myself well enough, which is very frustrating, of course. I see the benefit in this because it builds my patience and forces me to look at language acquisition through a different perspective, that I think most teachers don’t get.