Fall 2021 Faculty Appointments and New Hires at the Neag School

NYC Plans to Screen Nearly 200k Students in the Early Grades to Uncover Struggling Readers. Then What?

Chalk Beat (Devin Kearns is quoted about literacy screening)

UConn Names Next Austin Chair

UConn Today (Morgaen Donaldson was named the next Philip E. Austin Endowed Chair)

Rogers Award Legacy Lives on Through Innovative Art Projects

Editor’s Note: The Rogers Educational Innovation Fund awards $5,000 each year to an elementary or middle school teacher in Connecticut who leads an innovative classroom project.

Two innovative art projects funded by the Neag School’s Rogers Educational Innovation Fund, including a photojournalism art exhibit in Norwalk, Connecticut, and a mural project at a middle school in Hartford, Connecticut, brought together middle school students this past spring.

The fund is in place thanks to the support of the late Neag School of Education Professor Emeritus Vincent Rogers and his late wife, Chris, a lifelong teacher. While Professor Rogers wasn’t able to personally enjoy the fruits of the projects his fund supported due to his passing in December 2020, the projects lived on at a middle school and an art gallery.

The Future Is Us

Neag School alumna Jessica Stargardter ’16 (ED), ’17 MA, recipient of the 2019 Rogers Educational Innovation Award, is a gifted and talented educator for Norwalk (Conn.) Public Schools. Stargardter’s project, which involved a group of eight-graders from West Rocks Middle School calling themselves “The Future Is Us,” focused on having students document real-world societal challenges and empowering change in their communities through photojournalism.

“I made the project super student-centered, and the kids have taken so much ownership over their learning.”

— Jessica Stargardter ’16 (ED), ’17 MA

“I made the project super student-centered, and the kids have taken so much ownership over their learning,” Stargardter says. “It’s cool to see how my original vision of the project evolved through their input.”

Initially inspired by a graduate course in human rights and social justice, Stargardter incorporates what she learned in that class with her students. “Everything I do, everything I teach,” she says, “I’ve taken that with me and incorporated those themes into my teaching.”

To start, Stargardter asked the students about their personal passions, pushing them to articulate why particular topics mattered to them.

“We want to highlight how we already are tackling global problems on a larger scale,” the group wrote in their art exhibit opening program. “This exhibit aims to celebrate and gather the Norwalk community and empower others to take action.”

The students started to design the project at the start of the 2020 school year. Together with Stargardter and MAD Lab, a creative hub offering unique physical and digital art space in Norwalk, the students developed the exhibition over six months. It culminated in a gallery showing and community event that was open to the public earlier this summer.

In the beginning stages of the project, one of the students reached out to MAD Lab, which quickly became interested in helping with the project, offering more than a physical space to hold an exhibition.

“Staff from the MAD Lab decided to mentor the students, which has been wonderful,” says Stargardter. “They call themselves creatives, including all different types of artists. They meet weekly with the students and mentor them on where their art should go and how it is being portrayed. We paid for the art space from the grant, but the mentoring was free.”

Students carried the project out throughout the year despite a regularly changing learning model caused by the pandemic. Sometimes they met in person, and sometimes remotely. Most of the students were hybrid, meeting in-person half the time and virtually the other half of the time.

The students were responsible for all aspects of the project, including budgeting, securing the venue, and working with adults on requesting permissions.

“They are so excited, and a little bit stressed at the same time, but in a good way,” Stagardter says. “They were being pushed out of their comfort zone while also helping them realize their strengths. They are learning skills they can apply to real-world situations.”

Ultimately, the exhibit showcased the students’ mixed-media art, Polaroids and photographs, information about local organizations, and activities all focused on five subtopics: climate change, community service, mental health, self-love, and wearing masks. The student artists broke up into groups based on these topics and used the Polaroids to capture how they had been taking action to tackle these global issues.

Stargardter hopes to keep the project going with future students.

“I love how the community has come together,” she says. “It’s amazing to see, despite everyone’s challenges. It’s been cool to see for the kids and for the kids to feel like, ‘Oh, this matters.’”

Community Mural-Making

Jason Gilmore, the recipient of the 2020 Rogers Educational Innovation Award, is an art teacher at Hartford’s McDonough Middle School. Due to the pandemic, his winning proposal for creating a set of murals with students evolved into a virtual project.

“Working virtually this past school year has been challenging, especially for the kids,” says Gilmore.

For one, he says, “we had logistical challenges with securing and locating the supplies in the beginning, along with distributing the kits.”

Through a collective effort involving his family members, Gilmore put together more than 200 art supply kits. Then the effort expanded to the school staff — from the principal to the school secretary to the security guard — who helped distribute the kits to McDonough’s students.

“Some kits were dropped off at the students’ homes if they were not able to come to school,” he recalls. “It became a positive way to reach out to families.”

The art kits, he says, became an incentive for the kids to connect.

“This project, and the support from the Rogers Fund, meant a lot to me.”

— Jason Gilmore

Gilmore’s health issues initially required him to work remotely; as a result, he taught art virtually for part of the year from his basement through Google Meets.

“We looked at mural examples and talked about them, and we talked about various things and topics they cared about,” he says.

At first, some students did not feel confident sharing their art virtually with their peers. Gilmore found a way to resolve that.

“The students had different levels of English skills and different learning styles,” he says. “We used an online tool called Padlet, where the students could share their ideas without identifying [themselves].”

Students came up with themes based on topics they were passionate about and with which felt personal connection: “Celebrating Diversity,” “The Cultural of Food,” and “Celebrating Our Cultures (Hartford/USA, Puerto Rico, Dominican Republic, and Brazil).”

Five of the six murals were painted by the students in Gilmore’s in-person art classes. But when school went virtual, having students paint the larger mural proved to be another hurdle. To connect the students’ concepts in a final product, Gilmore took their ideas and drawings and put them into one composition aligned with the themes. Each class got a printout of the design and filled in the colors to create the final composition.

“I had to rethink art teaching, and expanded the process of community mural-making, something I had not thought of previously,” Gilmore says.

The final product included six painted murals installed at different locations throughout the school:

- Mural 1 “Food is Our Culture” – This mural, designed and painted by eight-grade virtual and in-person students, depicts the Black Lives Matter (BLM) 13 guiding principles. This group chose to focus on black villages, talked at length about their family traditions, and incorporated imagery of different foods as representations of their respective culture and families.

- Mural 2 “Music is in Our Roots” – This mural, designed by eighth-grade virtual students and painted by sixth-grade in-person students, focused on celebrating the students’ family roots. A commonality they depict across all their cultures is music, dance, carnival, and beach culture.

- Mural 3 “Beautiful Things” – This mural was designed and painted by virtual and in-person sixth-grade students focused on the 13 guiding principles of BLM in schools. The class chose to illustrate diversity: “We acknowledge and respect differences and commonalities.”

- Mural 4 “Celebrate Diversity” – This mural designed by eighth-grade virtual students and painted by Gilmore similarly focused on diversity and the 13 guiding principles of BLM in schools.

- Mural 5 “Pathways” – Designed by seventh-grade virtual students and painted by sixth-grade in-person students, this mural addresses the choices that middle school students face every day.

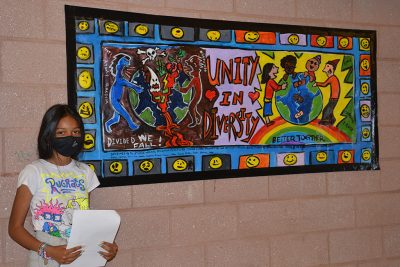

- Mural 6 “Unity in Diversity” – This mural, designed and painted by sixth-grade students, also focused on the 13 guiding principles of BLM in schools. The students worked together to create the statement: “We are better together … we fall when we are divided by our differences.”

For the future, Gilmore hopes the mural program stays — and grows — at the school.

“I want it to become a part of the art program and part of the school’s community outreach programs. I may even make it portable, including providing it for other teachers within this school and teachers at other schools in the community. Hopefully, the mural supplies will become regularly supported.”

Through the mural project, Gilmore says, students were able to develop new skills and relationships, and find new interests in art and or education.

“The project was successful through creative solutions of the whole community with people striving together, traversing barriers,” he says.

Gilmore is proud of the students’ creations and knows they can feel proud about their part in beautifying their community, even under challenging circumstances.

“This project, and the support from the Rogers Fund, meant a lot to me,” says Gilmore. “Just being able to keep focused with this project through being so disconnected from the school and the wonderful kids helped.”

Read more about Gilmore’s project through his blog, “The Mural Intervention Project Part 3,” and view a special message from Dean Jason Irizarry.

Related Rogers Award Stories:

Students Back to School With Anxiety, Grief, Social Skills Gaps

Editor’s Note: Co-written by Board of Trustees Distinguished Professor Sandra Chafouleas, along with alumna Amy Briesch ’05 MA, ’09 6th Year, ’09 Ph.D., an associate professor of school psychology at Northeastern University, this article on key issues for school mental health services with kids returning to classrooms originally appeared in The Conversation.

Even before COVID-19, as many as 1 in 6 young children had a diagnosed mental, behavioral or developmental disorder. New findings suggest a doubling of rates of disorders such as anxiety and depression among children and adolescents during the pandemic. One reason is that children’s well-being is tightly connected to family and community conditions such as stress and financial worries.

Particularly for children living in poverty, there are practical obstacles, like transportation and scheduling, to accessing mental health services. That’s one reason school mental health professionals – who include psychologists, counselors and social workers – are so essential.

As many kids resume instruction this fall, schools can serve as critical access points for mental health services. But the intensity of challenges students face coupled with school mental health workforce shortages is a serious concern.

Key issues

As school psychology professors who train future school psychologists, we are used to requests by K-12 schools for potential applicants to fill their open positions. Never before have we received this volume of contacts regarding unfilled positions this close to the start of the school year.

As researchers on school mental health, we believe this shortage is a serious problem given the increase in mental health challenges, such as anxiety, gaps in social skills and grief, that schools can expect to see in returning students.

As researchers on school mental health, we believe this shortage is a serious problem given the increase in mental health challenges that schools can expect to see in returning students.

Anxiety should be expected given current COVID-related uncertainties. However, problems arise when those fears or worries prevent children from being able to complete the expected tasks of everyday life.

Meanwhile, school closures and disruptions have led to lost opportunities for students to build social skills. A McKinsey & Co. analysis found the pandemic set K-12 students back by four to five months, on average, in math and reading during the 2020-2021 school year. Learning loss also extends to social skills. These losses may be particularly profound for the youngest students, who may have missed developmental opportunities such as learning to get along with others.

And it’s important to remember the sheer number of children under 18 who have lost a loved one during the pandemic. A study published in July 2021 estimates that more than 1 out of every 1,000 children in the U.S. lost a primary caregiver due to COVID-19.

Hiring more school psychologists

Hiring more school psychologists may not be simple. The National Association of School Psychologists recommends a ratio of 1 psychologist for every 500 students. Yet current estimates suggest a national ratio of 1-to-1,211. It’s like having to teach a class of 60 instead of 25 students.

Shortages are particularly severe in rural regions. There are also not enough culturally and linguistically diverse school psychologists.

Scarcity of school mental health personnel affects important student outcomes from disciplinary incidents to on-time graduation rates – especially for students attending schools in high-poverty communities.

To address these shortages, legislators have proposed federal bills that aim to expand the school mental health workforce. Meanwhile, local school districts and state education agencies are using American Rescue Plan funds to increase mental health training, hire additional mental health staff or contract with community mental health agencies.

Preparing all school personnel

We believe increasing the number of mental health providers in schools is important. Workforce increases, however, must be coupled with attention to readying all school personnel to cope with students’ anxiety, grief and gaps in social skills.

For example, when it comes to anxiety, schools can help students build both tolerance of uncertainty and coping skills through strategies such as seeking support, positive reframing, humor and acceptance. School mental health professionals can train other staff members on simple strategies to use in a nurturing relationship. Long-term benefits such as sense of belonging can happen when each student has an informal mentoring relationship that offers emotional nurturance and practical help.

More schools have adopted social-emotional learning curriculums in recent years. However, additional time may be needed to teach and reinforce basic skills such as taking turns and sharing.

In addition, school mental health personnel can assist with defining a clear process for identifying who needs help, and be ready to share resources about grief and how kids respond to loss.

Partnering with families and communities

Even with these efforts, schools cannot be expected to identify and meet all young people’s mental health needs. Strong partnerships with families and communities are critical.

Seeking input from families may offer valuable information about student experiences. This might be done, for example, by adding questions to beginning-of-the-year student forms. Knowing how families are experiencing loss or insecurities, for example, can help school mental health personnel plan for and target supports.

The youth mental health crisis requires a comprehensive response. We believe the priority should be ensuring equitable access to a mental health professional through school settings.

Improving Identification and Screening Processes for Indigenous Latinx English Learners

The Century Foundation (Research by Rebecca Campbell-Montalvo is mentioned)

Students are Returning to School With Anxiety, Grief and Gaps in Social Skills – Will There be Enough School Mental Health Resources?

The Conversation (Sandra Chafouleas co-writes essay on impact on mental health resources with students returning to school)

Helping Special Education Teachers Under Stress

Penn State News (Tamika La Salle is mentioned as being part of the $4M IES grant)

Ben Bronz Academy/Foundation Welcomes New Executive Director

We-Ha (Neag School alumna Gail Lanza has been appointed executive director)