CT Mirror (Neag alumnus and the U.S. Secretary of Education nominee Miguel Cardona is profiled; Casey Cobb and Robert Villanova are quoted)

Miguel Cardona is Set to Prove Himself on a Much Larger Stage

The 74 Million (Neag School alumnus and the U.S. Secretary of Education nominee Miguel Cardona is profiled; Robert Villanova and Barry Sheckley are quoted)

Neag School Accolades: Winter 2021

Congratulations to our Neag School alumni, faculty, staff, and students on their continued accomplishments inside and outside the classroom. If you have an accolade to share, we want to hear from you! Please send any news items and story ideas to neag-communications@uconn.edu.

In addition to the Dean’s Office and Department achievements, explore this edition’s list for Accolades from the following: Neag School Faculty/Staff; Alumni; Students; as well as In Memoriam.

Neag School Dean’s Office

The Neag School and its Alumni Board are pleased to announce the winners of the 2021 Alumni Awards:

- Outstanding Early Career Professional

Maria Enrique ’16 (ED), ’17 MA - Outstanding School Educator

James Wildman ’05 (ED), ’06 MA - Outstanding School Administrator

Lauren Rodriguez ’03 MA, ’06 6th Year - Outstanding Higher Education Professional

Sylvester Kent Butler Jr. ’85 (CLAS), ’94 MA, ’99 Ph.D. - Outstanding Professional

Melissa Thom ’15 MA

- Distinguished Alumna

Jamelle Elliott ’96 (BUS), ’97 MA

In addition, the Alumni Board named Lauren Dougher ’19 MA, a doctoral student in cognition, instruction, and learning technology; Jordane Virgo ’19 (CANHR), a master’s student in school counseling; and Elizabeth Canavan, a master’s student in the Integrated Bachelor’s/Master’s Program, the recipients of the 2021 Alumni Board Scholarship.

All awardees will be recognized at a celebration in March. Read more about the 2021 honorees and RSVP to the event.

UConn has been awarded a $179,000 grant from the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Postsecondary Education for a new research project, led by the Neag School’s Elizabeth Howard, who will serve as principal investigator and project director, and co-PI Manuela Wagner from UConn’s College of Liberal Arts and Sciences (CLAS). The research team also includes Aarti Bellara, Elena Sada ’20 Ph.D., and doctoral students Sandra Silva-Enos in the Department of Curriculum and Instruction and Dominique Galvez in CLAS’ Department of Applied Linguistics and Discourse Studies. Read more about the grant.

Dean Gladis Kersaint has been named to the American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education (AACTE)’s Board of Directors for a three-year term, beginning on March 1, 2021. Kersaint will share in the fiduciary and policy-setting responsibilities of AACTE, including approving the annual budget and financial audit, guiding the association’s work on programmatic initiatives, and other policy matters.

This fall, the American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education (AACTE) selected the Neag School to join its Holmes Scholars Program, a nationwide network of higher education institutions seeking to support students from historically underrepresented communities enrolled in graduate programs across the field of education. Diandra J. Prescod is leading the effort at the Neag School. Read more about the Holmes Scholars Program.

This fall, the American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education (AACTE) selected the Neag School to join its Holmes Scholars Program, a nationwide network of higher education institutions seeking to support students from historically underrepresented communities enrolled in graduate programs across the field of education. Diandra J. Prescod is leading the effort at the Neag School. Read more about the Holmes Scholars Program.

The Neag School Alumni Board hosted a social justice panel discussion in December featuring panelists and alumni Roszena Haskins ’17 Ed.D.; Anne McKernan ’11 ELP; Scott Ratchford ’86 (CLAS), ’99 6th Year, ’05 Ph.D.; and Jocelyn Tamborello-Noble ’03 (ED), ’04 MA, ’09 6th Year, all of whom serve in the West Hartford (Conn.) Public Schools system.

Department of Curriculum and Instruction (EDCI) and Teacher Education

In Fall 2021, the Neag School will launch a new program in American Sign Language (ASL) education. Recently approved by the Connecticut Board of Education, the program is designed to prepare aspiring educators interested in becoming ASL teachers. Learn about the program.

The Neag School’s fifth-year Integrated Bachelor’s/Master’s students volunteered with East Hartford (Conn.) High School in December by providing virtual one-on-one assistance for high school seniors working on their college applications and essays.

Department of Educational Leadership (EDLR)

A report by the Rand Corporation presents research findings on the University Principal Preparation Initiative (UPPI). The Neag School’s University of Connecticut Administrator Preparation Program (UCAPP) was one of seven university programs selected to participate in the Wallace Foundation-funded initiative, focused on improving training programs for aspiring school principals nationwide. As a result of the report, Richard Gonzales, Sarah Woulfin, Casey Cobb, and Jennifer McGarry published “Leadership, Defined, and Redesigned” for the December issue of The Learning Professional.

The sport management program co-hosted a virtual networking event with Temple University in December.

Department of Educational Psychology (EPSY)

The UConn Collaboratory on School and Child Health, led by Sandra Chafouleas, published a brief titled “Connecticut School Administrator Perspectives on Shifting Priorities During COVID-19.”

The UConn Collaboratory on School and Child Health, led by Sandra Chafouleas, published a brief titled “Connecticut School Administrator Perspectives on Shifting Priorities During COVID-19.”

Several EPSY faculty wrote chapters in the book Conceptions of Giftedness and Talent (Spring Link, 2021), including James Kaufman, who co-authored “Where Does Creativity Come From? What is Creativity? Where is Creativity Going in Giftedness?”; and Sally Reis, who authored “Creative Productive Giftedness in Women: Their Paths to Eminence.” In addition, Reis co-authored a chapter with Joseph Renzulli titled “The Three-Ring Conception of Giftedness: A Change in Direction from Being Gifted to the Development of Gifted Behaviors.”

Faculty and doctoral students in the Renzulli Center for Creativity, Gifted Education, and Talent Development, including doctoral students Allison Kenney, Susan Dulong, Shannon Holder, as well as E. Jean Gubbins, co-wrote, along with others, “Beyond a Coefficient: An Interactive Process for Achieving Inter-Rated Consistency in Qualitative Coding” for the December issue of Qualitative Research.

This week, the Renuzlli Center also begins a series of free live webinars for educators and parents on such topics as perfectionism, creativity, and student motivation.

Faculty/Staff

Michele Back participated in a virtual panel presentation titled “Negotiating Participant Distress and Negative Perceptions of Language in Multilingual Research,” for the SRS-TEFLON 1st International Webinar in December.

Todd Campbell co-published “Advancing Minoritized Learners’ STEM Oriented Communication Competency Through a Science Center-Based Summer Program” for the December issue of Journal of Museum Education. A recent panelist for Math for America’s MFA Wednesday Webinar Series, he also co-authored “How Can We Make Informed Decisions to Keep Ourselves and Communities Safe During the COVID-19 Pandemic?” for the National Science Teaching Association and, with Byung-Yeol Park and colleagues, “On the Cusp of Profound Change: Science Teacher Education in and Beyond the Pandemic” in the Journal of Science Teacher Education.

Sandra Chafouleas and Neag School alumna and postdoctoral research associate Emily Iovino 15 (ED), ’16 MA, ’20 Ph.D. wrote “COVID-19 Means a Lot More Work for Families of Children With Disabilities, but Schools Can Help” for The Conversation. Chafouleas also wrote “Here’s Why Silver Linings are Important to Education in 2021” for her Psychology Today blog, and was a featured speaker for the UConn Provost’s Distinguished Speaker Series in December, which was featured by UConn Today.

Morgaen Donaldson published Multidisciplinary Perspectives on Teacher Evaluation (Routledge, 2020).

Hannah Dostal co-authored with Joan Weir, a doctoral student in curriculum and instruction, and others, “Literacy Development at Camp: Leveraging Language Models” for the November issue of The Reading Teacher.

Hannah Dostal co-authored with Joan Weir, a doctoral student in curriculum and instruction, and others, “Literacy Development at Camp: Leveraging Language Models” for the November issue of The Reading Teacher.

Jennifer Freeman and collaborators from Lehigh University received a $500,000 grant from the Institute of Education Sciences to research improving college and career readiness for students with emotional and behavioral disorders. Read more about the grant.

Nicholas Gage was recognized with the Council for Exceptional Children’s Division of Research Early Career Research Award. Gage was a postdoctoral student under an IES grant co-led by Sandra Chafouleas and George Sugai.

Doug Glanville was featured in a Kiplinger podcast episode about his years playing Major League Baseball as well as on his experience and interest in investing.

Preston Green participated in a podcast episode with OnEducation in January. He was also in a school choice panel in December hosted by the Brookings Institute.

Robin Grenier co-authored “Not All Those Who Wander Are Lost: Critically Reflective Research for a New HRD Landscape” for the November issue of Advances in Developing Human Resources.

Joseph Madaus co-published several articles for a special issue of the Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, titled “Challenges and Opportunities for Assessing, Evaluating, and Researching Disability in Higher Education,” which came out in Fall 2020. Madaus also co-authored with doctoral student Ashley Taconet, alums Lyman L. Dukes ’95 MA, ’01 Ph.D. and Nicholas Gelbar ’06 (CLAS), ’07 MA, ’11 MA, ’12 6th Year, ’13 Ph.D., along with others, “Using the APP Tool to Promote Student Self-Determination Skills in Higher Education (Practice Brief)”; with alums Manju Banerjee ’07 Ph.D. and Adam R. Lalor ’17 Ph.D., among others, “A Survey of Postsecondary Disability Service Websites Post ADA AA: Recommendations for Practitioners”; and with Lalor, among others, “Leveraging Campus Collaboration to Better Serve All Students with Disabilities.” He also co-published with Gelbar, Dukes, Taconet, and others, “Are There Predictors of Success for Students With Disabilities Pursuing Postsecondary Education?” for the December issue of Career Development and Transition for Exceptional Individuals.

Alan Marcus was appointed to the Hartford City Council Columbus Task Force, where he collaborates with council members, historians, educators, museum staff, and community members to recommend to the mayor and City Council a process for changes to the memorialization of Christopher Columbus, including honoring “local and national heroes that Hartford’s past, current, and future residents will be proud to honor.”

Glenn Mitoma reflected in a recent piece on International Human Rights Day at UConn. Read the story here.

Bianca Montrosse-Moorhead presented “Working with Youth in Evaluation” for the EvalYouth Global Taskforce 4 Webinar Series in December.

David Moss co-wrote a chapter titled “Going Global in Teacher Education: Lessons Learned from Scaling Up” in Study Abroad for Pre- and In-Service Teachers (Routledge, 2020).

John Settlage published a review on Science in the City: Culturally Relevant STEM Education and Science in Diverse Classrooms: Real Science for Real Students for the September issue of Science Education.

George Sugai wrote an essay “IDEA45: Happy Birthday IDEA” for the Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services Blog.

Saran Stewart was a panelist for “SEL Global Leadership Series: Looking Back at 2020” for Knowledge Hook, a virtual panel in December.

Robert Villanova participated on a panel titled “How the Preparation of Superintendents Has Changed to Meet Today’s Challenges” in January for The RESC Alliance and the Connecticut Association of Boards of Education. In addition, he and alumnus Nathan Quesnel ’01 (ED), ’02 MA, along with another colleague, co-wrote “Shared Governance: How Pandemic Partnerships Can Lead to Progress and Offer Promise” in December for American City and County.

Jennie Weiner co-published “When is Psychological Safety Helpful? A Longitudinal Study” for the December issue of the Academy of Management and co-published “Rethinking Social Mobility in Education: Looking Through the Lens of Professional Capital” for the December issue of Emerald Insight. Earlier this month, she was featured as a New England News Collaborative guest for a segment on how schools are taking on pandemic challenges. In addition, she co-published The Strategy Playbook for Educational Leaders (Routledge, 2020). Read an excerpt from the book.

Jennie Weiner co-published “When is Psychological Safety Helpful? A Longitudinal Study” for the December issue of the Academy of Management and co-published “Rethinking Social Mobility in Education: Looking Through the Lens of Professional Capital” for the December issue of Emerald Insight. Earlier this month, she was featured as a New England News Collaborative guest for a segment on how schools are taking on pandemic challenges. In addition, she co-published The Strategy Playbook for Educational Leaders (Routledge, 2020). Read an excerpt from the book.

Eli Wolff co-published “The Power of Sport for Inclusion: Including Persons with Disabilities in Sport” for Sport and Dev.

Sara Woulfin published “From Hunkering Down to Caring Up” for the December edition of the American Educational Research Association’s Division L newsletter. She was also elected to the executive committee of the University Council for Educational Administration.

Students

Jia Cai, a higher education and student affairs master’s student, published a commentary titled “COVID-19 Realities Expose Inequities in Online Learning” for the Hartford Courant.

Robert Cotto, a doctoral student in educational leadership, co-wrote with Preston Green and another colleague a commentary titled “Fixing Connecticut School Finance: The Time is Now” for CT Mirror. Cotto also published “Unpacking a Misplaced Response to Calls for Police Abolition in Hartford” for the same publication.

Daron Cyr, a doctoral student in educational leadership, published a research brief titled “The Payoff of Preschool: Investing in Connecticut’s Youngest Residents” for the newly renamed Center for Education Policy Analysis, Research, and Evaluation (CEPARE).

Luis Ferreira, an incoming doctoral student in educational psychology, has been named the recipient of the Joseph Renzulli and Sally Reis Renzulli Fund for Graduate Studies in Gifted Education. With professional experience in working with top athletes, some of whom have become Olympic champions, Ferreira will integrate his expertise in motivation into his research on talent development in students. Read his story.

Sandra Sears, a doctoral student in educational psychology, wrote a research brief titled “Supports for Students with Disabilities at the Post-Secondary Level.”

Emily Tarconish, a doctoral student in educational psychology, was awarded a $2,000 UConn Doctoral Dissertation Fellowship from the UConn Graduate School.

Kim Velasquez, an Integrated Bachelor’s/Master’s Degree student, wrote “My Experience as a Distance Learning Elementary School Intern” for UConn’s Center for Career Development.

Alumni

Nancy Abohatab ’76 (CLAS), ’81 MA retired from UConn’s Department of Residential Life after almost 40 years. After transferring to UConn during her junior year, she became a resident assistant (RA). That was the first year that UConn had entirely changed over from having house mothers to resident assistants. During her graduate program, she became a head resident (graduate supervisor of RAs).

Rodney Bass ’77 MA served as a panelist this month for the UConn Alumni #ThisIsAmerica discussion, titled “Exploring the History of Racism at UConn.”

Latanya Brandon ’20 Ph.D. was an invited speaker with the National Science Teaching Association’s District I, II, & VI virtual meeting on Racial Equity in January.

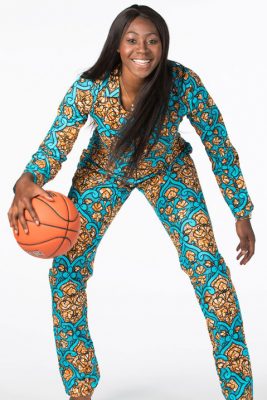

Batouly Camara ’19 (ED), ’20 MA was selected as a Forbes 30 Under 30 for Sports. A former UConn women’s basketball player, she is the founder of Women and Kids Empowerment.

President-Elect Joe Biden chose Miguel Cardona ’01 MA, ’04 6thYear, ’11 Ed.D., ’12 ELP as the nominee for U.S. Secretary of Education. Read more about Cardona’s nomination.

Casey Cochran ’15 (CLAS), ’17 MS, former UConn quarterback, was featured by NBC Connecticut about releasing a musical album.

Craig Cooke ’01 6th Year ’07 Ph.D. is featured about his new role as superintendent of Madison (Conn.) Public Schools. He most recently served as superintendent of Windsor (Conn.) Public Schools.

Madison Corlett ’16 (ED), ’17 MA helped fourth-grade students in Mansfield, Connecticut organize a fundraiser to benefit local businesses and essential workers.

Isabella “Ivy” Horan ’19 (ED), ’20 MA was featured by WTNH News 8 for her multicultural classroom at Mayberry Elementary School in East Hartford, Connecticut.

Neag School alumna Kristi Kaeppel ’20 Ph.D. and Robin Grenier are featured by UConn Today about a paper they published on friendships in academia. Read about their research.

Taylor Koriakin ’11 (CLAS), ’16 MA, ’19 Ph.D., co-published with Sandra Chafouleas, along with others, “Development of a Comprehensive Tool for School Health Policy Evaluation: The WellSAT WSCC” for the November issue Journal of School Health.

Tricia Lee ’20 6th Year was named assistant principal of The Friendship School in Old Lyme, Connecticut.

Neag School alumna Laura Rodriguez ’16 (ED), ’17 MA, along with doctoral student Byung-Yeol Park, Todd Campbell, David Moss, and others, co-published “Investigating Human Impacts on Local Water Resources & Exploring Solutions” for the November/December 2020 issue of The American Biology Teacher. Rodriguez also co-presented with Campbell, Moss, and Professor Emeritus John Volin from UConn’s Department of Natural Resources and the Environment “STEM Identity Authoring in Collaborative Intergenerational Partnerships” for the Association for Science Teacher Education’s virtual conference in January.

In Memoriam

George Allen (former Neag School faculty)

Susan K. Azia ’65

Rosemarie E. Driscoll ’90

Isabel B. Higgins ’77

Charles J. Mitchell ’61

Barbara G. Reinhardt ’80

Vincent Rogers (faculty)

Gretchen K. Sheridan ’71

Gregory E. Wissell ’20

Neag School Ph.D. Student’s Research to Combine Sport, Education

Luis Ferreira will begin his Ph.D. studies in educational psychology this spring after facing unforeseen obstacles in obtaining a visa to study in the United States. Accepted to UConn’s Neag School of Education in February 2020, he has made tremendous sacrifices to pursue his doctorate, including moving away from his wife and family in Brazil.

Ferreira was unsuccessful in obtaining a visa in Brazil due to COVID-19 regulations, so he moved to Portugal for four months, where he holds dual citizenship. He secured his student visa while in Portugal and arrived in Connecticut in late December.

“It makes me feel very special to be able to go there,” said Ferreira while anticipating his arrival at UConn. “I’m going there to learn and to translate what I learn to other people.”

Ferreira’s story of sacrifice and enthusiasm for studying at the Neag School, as well as his impressive skill set and experiences, earned him scholarship support through the Joseph Renzulli and Sally Reis Renzulli Fund for Graduate Studies in Gifted Education.

“I hope to contribute what I’ve learned to help [students] develop their talents.”

— Luis Ferreira,

Joseph Renzulli and Sally Reis Renzulli Fund Recipient

The scholarship is awarded by faculty nomination, and determined based on financial need and desire to make a difference in education. Joseph Renzulli and Sally Reis have been at UConn for decades, making the graduate program in Gifted Education and Talent Development their life’s work.

“We’ve had the opportunity to work with and mentor students from all over the world,” says Reis. “They make a very large investment, and we wanted to make an investment in them.”

Reis says they selected Luis because of his passion, creativity, and desire to make a difference in education through his future work.

“It’s an honor for us to see him get this award,” says Reis. “He wants to go back to his country and make a difference in education, and we are so proud to support that dream.”

An Intersection of Sport and Education

Ferreira has spent several years working with top athletes, some of whom became Olympic champions and world-record breakers. While working towards his master’s degree at the University of Brasília, he trained athletes using psychological tools such as mentalization, a technique that uses mental rehearsal to prepare and test strategies for competition. He also used the biofeedback technique on athletes which utilizes machines that read electric signals in the body and help athletes with stress control.

Ferreira described these techniques as self-regulation tools, designed to increase maximum potential. He’s studied this methodology in major athletic competitions across the globe, including Germany, Scotland, Portugal, and Mexico.

“During my research, I found that several of the texts I was reading came from people at UConn, people like Joseph Renzulli, Sally Reis Renzulli, and Del Siegle,” says Ferreira.

“He has worked as a sports psychologist and he’s worked with world-class athletes. He is interested in motivation and what causes people to really develop to their full potential.”

— Del Siegle, Lynn and Ray Neag Endowed Chair for Talent Development

He learned from reading Professor Del Siegle’s work that people need to use tools that are meaningful to them, especially self-regulation tools, in order to develop their talents. Applying this concept to athletes, Ferreira found the tools used were well-understood and accepted.

“I took something that Professor Del Siegle was proposing, and I saw it in a practical way in sports, and then I thought maybe now’s the time to attempt coming to UConn to see if I can study with the people that I had been reading about,” says Ferreira.

Siegle now serves as Ferreira’s academic advisor. He says there was a natural connection between them because they are both interested in developing excellence, but have been working in different domains. The two hope to learn from each other and see how their findings in the education and sport worlds overlap.

“The cool thing about it is there is this interdisciplinary thing going on because he has worked as a sports psychologist and he’s worked with world-class athletes,” says Siegle. “He is interested in motivation and what causes people to really develop to their full potential.”

Transitioning to the Academic World

Ferreira had always intended to enter the academic field after working in sport psychology, referring to education as “the key to a better world.” He says he hopes to apply the talent development approaches he learned from working with athletes toward helping students reach their highest potential.

“I hope to contribute what I’ve learned, not to make people world champions, but to help them develop their talents in an easier way and help them deal with stress in an easier way so they don’t feel overwhelmed by situations,” says Ferreira.

He says he never could have imagined receiving a scholarship from Renzulli and Reis, describing them as two of the most influential scientists in the field of talent development.

“It’s an honor to receive this scholarship and to know that your peers respect you,” says Ferreira. “I know who I am, and I know what I can contribute, but I feel thankful and I feel I should work a lot to deserve this.”

For more information on supporting students like these, visit s.uconn.edu/neaggiving.

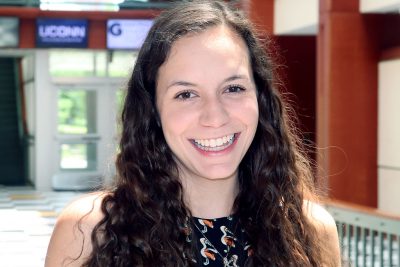

Neag School Names Recipients of 2021 Alumni Board Scholarship

Lauren Dougher ’19 MA, a doctoral student in cognition, instruction, and learning technology; Jordane Virgo ’19 (CANHR), a master’s student in school counseling; and Elizabeth Canavan, a master’s student in the Integrated Bachelor’s/Master’s Program, have been named the recipients of the Neag School of Education Alumni Board Scholarship for 2021.

The Alumni Board Scholarship provides a $1,000 award annually to students enrolled in a Neag School master’s, doctorate, or sixth-year program with proven academic excellence or demonstrated financial need. The scholarship is intended to invest in the education and experience of Neag School students.

“We were very impressed with the application materials the students shared, as well as their commitment to their education and future careers,” says Neag School Alumni Board President Megan Parrette ’12 6th Year, ’17 ELP. “We are delighted to play a small part in supporting the student’s graduate experience at UConn and look forward to their journeys as they go on to do great things in the world.”

“It is a very fulfilling job to watch students who start out with little confidence in their academic abilities flourish into students who know they can succeed in school.”

— Lauren Dougher,

2021 Alumni Board Scholarship Recipient

Combining Research and Teaching to Help Others

A mentor for UConn student-athletes since 2019, Dougher applies her education knowledge in assisting them with their academics. She works as an extension of the professional UConn staff in mentoring the students one-on-one, ensuring their success by promoting better study habits and time management skills, and providing assistance for their understanding of various course materials.

“It is a very fulfilling job to watch students who start out with little confidence in their academic abilities flourish into students who know they can succeed in school,” Dougher says.

Dougher has also served as a graduate assistant and lead instructor for graduate students in the Neag School since 2018. Since the pandemic hit, she also has assisted with UConn’s Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning, working one on one with faculty to help them with the fast-paced transition to online instruction.

In addition, she is researching first-year students at UConn’s School of Engineering, assessing students’ self-efficacy, creativity, and persistence. This research has led to a co-presented paper at a regional academic conference.

Combining her research and teaching experience, Dougher says she hopes to become an instructional designer where she can “continue helping others and applying all I have learned while furthering my understanding of education.”

Losing her mother this past fall, Dougher was not sure if she was going to be able to continue her studies and is very grateful for the Alumni Board Scholarship support. “With this scholarship, I will be able to take the time I need for myself to grieve and heal without worrying if it will set me back to the point that I cannot afford to stay at UConn,” she says. “I am so grateful to be a recipient of this scholarship and am proud I can continue to embody the values of the Neag School with my current and future endeavors.”

Finding His Purpose of Helping Others

Virgo is among numerous recent graduates across the U.S. who have faced challenges finding employment. After graduating from UConn in 2019 with a degree in nutritional sciences, he could not find a job – a dilemma worsened by the pandemic.

“After six months, I was finally hired as a deli worker at Big Y. It was a humbling experience to go from lab work and research papers to slicing meats and cheeses,” Virgo shared in his scholarship application.

He had enjoyed the nutritional science courses as an undergraduate student, but the science end started “to look like a new language.” Virgo decided to change his academic path and fulfill his initial dreams of helping those in need while also enjoying the coursework.

After deciding to pursue a master’s degree in counseling, Virgo sought work as a substitute teacher as well as a job coach for individuals with disabilities to help cover the cost of graduate school. In the latter role, he teaches high school students with autism how to transition from their special education program to the workforce, promoting job coaching, career counseling, and self-efficacy.

His connection to helping students stems from his time as an undergrad at UConn. In a mentorship role with UConn Connects, he assisted students who needed academic and social support by counseling them on success strategies. He also gained hands-on experience with students as a resident assistant.

As an undergrad, Virgo also was a student leader across campus. In addition to mentoring and being a resident assistant, he engaged in service learning with a childcare facility in Hartford, Connecticut, served as a UConn ambassador on the Avery Point campus, and worked with the Office of First-Year Programs. And while serving as a student mentor at ScHOLA2RS House, a Learning Community designed to support male students’ scholastic efforts who identify as African American/Black, Virgo connected with a mentor of his own who helped him discover his purpose.

“As a black man who never had black professionals in my schools, I plan to be that resource for marginalized, at-risk, and low-income students,” he says. “My mentor always says, ‘Pursuing purpose.’ This is my purpose.”

“As a black man who never had black professionals in my schools, I plan to be that resource for marginalized, at-risk, and low-income students.”

— Jordane Virgo,

2021 Alumni Board Scholarship Recipient

“When I got this scholarship, the feeling of being chosen for something is euphoric (after getting turned down for other scholarships). My confidence has gone up, and my drive has gone up,” he says. “I feel like an NFL prospect who is passed up by team after team and finally gets picked, then all the teams that passed up on him have to watch him absolutely work harder than anyone else, give maximum effort day in and day out, and just wish they had taken a closer look before passing up.”

“I feel recognized and I’m excited to show everyone just what a great stock they just invested in,” he adds.

Using a Love of Math to Combat Math’s Negative Stigma

Growing up, Canavan endured childhood trauma due to her father’s frequent mental hospital admissions. “Everything plummeted after he was in a tragic car accident with my younger sister,” she shared in her scholarship essay. “This was traumatic for everyone … and this started a downward spiral for my family.”

Canavan’s sister’s recovery was happening amid her father’s deteriorating mental state, leading to his incarceration and her parents’ divorce. This experience left her entire family emotionally drained and financially challenged.

Canavan says she chose to focus her energy on her “academics and activities,” including her college applications and mental health. During this time, she says she became close with some of her teachers and “witnessed firsthand how educators can impact students’ lives.”

“I realized that I wanted to be that person for my future students,” she wrote.

At the same time, she “witnessed and reflected” how some of her peers had been “turned off to math” at an early age and thought “they were inferior” to the subject. She observed how none of her secondary math teachers attempted to “combat this negative math stigma” that impacted so many of her peers.

“I am extremely grateful for these scholarships because they are giving me the opportunity and the honor to further my education here at UConn.”

— Elizabeth Canavan,

2021 Alumni Board Scholarship Recipient

Her confidence in and enjoyment of mathematics, while seeing the lack of encouragement from her teachers, led her to want to be a math educator.

Through her clinical practicum at E.O. Smith High School and Sage Park Middle School, Canavan has observed algebra and geometry classes, collaborated with the instructor, and assisted in student learning. As a student teacher at Hall Memorial School, she also planned and implemented mathematics lessons for on-campus and remote learners.

“I am extremely grateful for these scholarships because they are giving me the opportunity and the honor to further my education here at UConn,” says Canavan. “Because of these gracious gifts, I am able to pursue my career in math education and hope to influence others in the future.”

Alumni Board Scholarship recipients Lauren Dougher, Jordane Virgo, and Elizabeth Canavan will be formally recognized at the 2021 Neag School Alumni Awards Celebration, taking place virtually in March. Register online for the event at s.uconn.edu/NeagAlumni2021. For more information on supporting students like these, visit s.uconn.edu/neaggiving.

Who is Miguel Cardona? Education Secretary Has Roots in Classroom, Principal’s Office

Education Week (Neag School alumnus and the U.S. Secretary of Education nominee Miguel Cardona is profiled)

Fixing Connecticut School Finance: The Time is Now

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in CT Mirror. Bruce Baker is from Rutgers University; Robert Cotto is a Neag School doctoral student in educational leadership and faculty member at Trinity College; and Preston Green serves as the John and Maria Neag Professor of Urban Education at the Neag School.

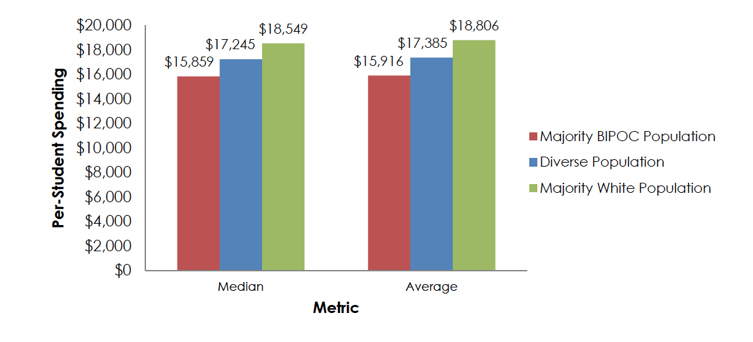

The COVID pandemic has laid bare the extent of inequalities across Connecticut’s cities, towns, and school districts and the children and families they serve. Connecticut has long been one of our nation’s most racially and economically segregated states, while also one of the wealthiest. In the past decade, those inequities have worsened along both economic and racial lines. In 2021, Connecticut continues to face the interrelated challenges of segregation and school funding equity and adequacy. Connecticut must do better.

In two recent articles, we showed that Connecticut school funding continues to systematically disadvantage students in schools and districts serving predominantly Latinx communities. This finding is not new, with districts like Bridgeport, Waterbury, and New Britain recognized in numerous national reports as being among the most financially disadvantaged school districts in the nation. For a period, Connecticut appeared to do somewhat better on behalf of predominantly Black school districts, but this was largely a function of additional aid directed specifically at magnet school programs in Hartford and New Haven, and not by the design of the general aid formula. In a forthcoming article, we find that Black-white disparities in state and local revenues and in property taxation are among the largest in the nation and have worsened in recent years.

State school finance systems require constant evaluation and recalibration. Connecticut schoolchildren have waited far too long, especially those in the state’s low income black and Latinx communities.

Inequities in property taxation, fueled by a long history of exclusionary zoning and racial discrimination, are major contributors to the state’s school finance problem, and cannot be ignored. Municipal fiscal dependence is also a problem. Having a system in which local public schools rely on city and town budgets, where those budgets are based on prior taxing and spending behavior rather than current needs exacerbates the unevenness of school funding, hitting especially hard, schools in cities like Bridgeport. Above all, however, the state’s general aid program for schools – The Education Cost Sharing Formula (ECS) – falls short of addressing these inequities, and has never been calibrated appropriately to meet the needs of all of the state’s children.

Yes, longer-term structural changes to the property tax system, housing, and school segregation must be on the table. But more immediate steps are in order, to reform the state’s Education Cost Sharing Formula. The primary objective of a state school finance system is to ensure that regardless of where a child in the state lives or attends school, that child should have equal opportunity to succeed in school and life. Whether that system relies exclusively on local public school districts, or includes alternatives such as charter schools among the delivery mechanism to achieve these goals, choice is not a substitute for equitable and adequate funding. Equitable and adequate funding is a prerequisite condition, and necessary for closing the state’s racial and economic achievement gaps.

State school finance systems must accomplish two goals simultaneously:

- Accounting for the differences in needs and costs across districts, cities, and towns associated with providing equal educational opportunity;

- Accounting for the differences in local capacity to generate revenues toward the provision of equal educational opportunity.

Just like the name of the current formula – Education Cost Sharing Formula – suggests, the goal is to identify the “costs” of educating children from one school and district to the next, and then determine how to “share” those costs between local communities and the state. ECS is the primary mechanism by which the state shares the cost of educating children in Connecticut’s public schools. But ECS has never been based on any actual analysis of those costs or how those costs vary from one location to the next and one child to the next.

To clarify, “cost” per se, is what is outlined under the first point above – the “costs” of achieving specific outcome goals. Any legitimate conception of “costs” necessarily involves consideration of outcomes. The state must decide what those goals are and how they should be measured. And the state should engage in an analysis of the costs of providing all of the state’s children with equal opportunity to achieve those outcomes. This is what we mean by “calibration.” Connecticut needs this information sooner rather than later to take steps toward reforming or replacing ECS.

A recent national analysis estimated the costs of achieving the modest goal of national average outcomes on reading and math assessments, a benchmark that Connecticut children generally exceed. Even against that low bar (per pupil cost of achieving national average outcomes), a handful of Connecticut districts fall behind. Specifically, Bridgeport, Waterbury, and New Britain have spending gaps exceeding $5,000 per pupil. Similar analyses have been conducted in recent years to advise state legislatures in Vermont, New Hampshire, and Kansas. Two things we know well from these analyses:

- It costs more to achieve higher and broader outcome goals

- It costs more to achieve these goals in some locations and for some children than others

There are significant additional costs of achieving common outcome goals in locations with concentrated child poverty, large shares of emerging bilingual students with added needs, etc. Connecticut’s Education “Cost” Sharing formula falls well short of addressing these “costs.”

It will undoubtedly require a substantial boost in total state aid to bring all districts to spending levels sufficient to achieve a robust set of outcomes. Achieving more will cost more, plain and simple. Again, Connecticut is a wealthy state that can afford, through higher taxes on its most affluent residents, to address these issues without fearing a mass exodus.

To summarize, we propose a three-step process toward reforming the state school finance system to mitigate the state’s persistent racial and economic disparities in school funding and student outcomes:

Step 1: Conduct rigorous analyses to answer the question: What is needed to achieve equal opportunity for all of the state’s children to achieve a sufficiently robust set of outcomes?

Step 2: Recalibrate ECS with a formula specifically designed to hit these cost targets through a combination of a) equitable local effort and b) sufficient state aid;

Step 3: Fund it! (Raise sufficient tax revenues to support the system.)

Keep it up! Revisit. Evaluate. Recalibrate.

No state school finance system remains adequate in perpetuity without checks and balances. Goals change as do other demands on local public schools. State school finance systems require constant evaluation and recalibration. The time is now to start these steps. Connecticut schoolchildren have waited far too long, especially those in the state’s low income black and Latinx communities.

To Save Democracy, Recommit to Principles of the Rule of Law and Human Rights at Home

Editor’s Note: This commentary was originally published in CT Mirror following the U.S. Capitol riots last week. Glenn Mitoma is the director of Dodd Human Rights Impact and assistant professor of education and human rights and Kathryn Libal is the director of the Human Rights Institute and associate professor of social work and human rights.

The fascist riot at the U.S. Capitol is a fitting denouement of the Trump Presidency. His incitement of thousands of white supremacists, conspiracy theorists, and others caught in the thrall of his cult of personality demonstrated once and for all that there is nothing he won’t do to cling to power – and nothing some won’t do to keep him there.

Whether by the 25th Amendment, a second impeachment, or the inexorable approach of January 20, Trump’s presidency is ending. But for the United States to recover from this near miss with a Trump dictatorship, we must commit to rebuilding our democracy on a foundation of accountability, truth-telling, and human rights.

That Congress reconvened to certify the Electoral College vote after the building was cleared is a relief. Likewise, the recent refusal of military leaders to entertain Trump’s reported fantasies of declaring martial law to preserve his rule, and the relative efficiency with which courts across the country have dismissed the meritless lawsuits brought to challenge the election results, are heartening. But the impunity with which the mob was allowed to ransack the Capitol building is a mirror image of the impunity with which, for four years, the President has assaulted our democratic institutions. Defeating Trump at the ballot box and expelling the mob is not enough.

For the United States to recover from this near miss with a Trump dictatorship, we must commit to rebuilding our democracy on a foundation of accountability, truth-telling, and human rights.

Seventy-five years ago, Americans recognized that defeating the fascism of Adolf Hitler required more than a military victory; it also required the reassertion of the rule of law on a global scale through the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg. U.S. Supreme Court Justice Robert Jackson led the Allies effort to hold the Nazi leadership to account for war crimes, crimes against peace, and crimes against humanity. “That four great nations, flushed with victory and stung with injury stay the hand of vengeance and voluntarily submit their captive enemies to the judgment of the law,” Jackson said in his epic opening address, “is one of the most significant tributes that Power has ever paid to Reason.”

Reasserting the rule of law within the United States requires not only rejecting the outlandish claims of election fraud, but also holding Trump and other officials accountable for the abuses of power, corruption, and possible crimes they may have committed. As with Nuremberg, President-elect Joe Biden’s Justice Department can demonstrate that even “men who possess themselves of great power” are not above the law.

But we will need to go beyond prosecutions for wrong-doing to gain a full understanding of what has transpired under the Trump administration. President-elect Biden has suggested that his presidency will inaugurate a time of “healing” for the United States. Lessons from post-authoritarian societies, like post-Apartheid South African’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, show that this process of healing must begin with a full accounting of the devastating impact of the Trump era. Doing so will not only ensure that Trump and his accomplices are not allowed to “get away with it,” but also will open the process of national truth-telling.

Finally, a clear lesson of the past four years has been that we need to deepen our institutional commitments to realizing human rights—another lesson of the post-WWII period. While Jackson prosecuted Nazi crime, Eleanor Roosevelt led the fledgling United Nations in drafting the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Far too long, Americans have regarded fascism and other threats to human rights as something only other countries have to worry about. To build a broader democratic culture, we will need to bring human rights home. Domestic human rights organizations, which have been calling for establishing a non-partisan human rights commission, could take leadership in drawing upon both domestic and international norms to develop a platform to strengthen civic engagement and democratic practices that are key to resisting authoritarianism.

Supporting the rule of law by holding officials accountable, constructing an accurate account of the recent past, and recommitting to human rights at home are essential to restoring the confidence in government that underlies our shared national life. Such work can help create a new sense of community, which is a fundamental aspect of a healthy democracy.

Mansfield Students Organize Fundraiser to Assist Local Businesses, Essential Workers

Hartford Courant (Fourth-grade students, led by Neag School alumna Madison Corlett, organized a fundraiser to help both local businesses and essential workers)

Announcing the 2021 Neag School Alumni Awards Honorees

The Neag School of Education and its Alumni Board are delighted to announce the 2021 Neag School Alumni Awards honorees. Six outstanding graduates will be formally recognized at the School’s 23rd annual Alumni Awards Celebration on Saturday, March 13, 2021.

Outstanding Early Career Professional

Maria Enrique ’16 (ED), ’17 MA

A graduate of the Neag School’s Integrated Bachelor’s/Master’s Program, Maria Enrique today is an eighth-grade math teacher at Ellington (Conn.) Middle School known for her welcoming energy and student-centered, innovative teaching. Within her first three years of teaching, she has actively taken part in events, professional development opportunities, and other activities that are making a positive impact on the community in numerous ways. In support of students at Ellington Middle, Enrique advises a statewide student math competition and an after-school study skills club, serves as a track and field coach, has established a summer school math program and a homework help club, and has chaperoned several student trips beyond the traditional classroom. She also has presented to hundreds of math teachers from across the state, while also seeking out ways to share her insights and experience with pre-service teachers, including current Neag School students.

Outstanding School Educator

James Wildman ’05 (ED), ’06 MA

In addition to supervising and evaluating a staff of 19 fellow world languages educators at Glastonbury (Conn.) High School, James Wildman serves as head teacher for the school’s Foreign Languages Department. He teaches Spanish, advises for the Model UN and Foreign Language Honor Societies, and has coordinated student study abroad programs in Spain, Costa Rica, Russia, and China. He also has been instrumental in securing funding for the district through a federal grant program that supports the teaching and learning of languages. Presenting at state, regional, and national levels, Wildman has continued to share his expertise with practicing teachers amid the pandemic through presentations on creating virtual classrooms and using digital choice boards. An award-winning educator, a leader in state and regional foreign language associations and workgroups, as well as a member of the Board of Directors for the Northeast Association for the Teaching of Foreign Languages, he continues to advocate at all levels for language learning.

Outstanding School Administrator

Lauren Rodriguez ’03 MA, ’06 6th Year

Lauren Rodriguez has served since 2013 as principal of Southeast Elementary School in Mansfield, Connecticut. There, her compassionate leadership and supportive approach to engaging with all members of the school community has fostered an inclusive environment that has ultimately earned the school recognition numerous times as a Connecticut School of Distinction. From implementing enrichment clusters for students to integrating positive behavior supports to allow for healthy social and emotional development, Rodriguez is known for having built strong and positive relationships with teachers as well as parents. She has proven herself not only as a leader, but also as a hands-on collaborator, having, for instance, co-written the district’s grade-level benchmarks for 21st century learning and led the professional development rollout for three district elementary schools. Over the years, Rodriguez also has remained closely engaged with the Neag School community, including as a mentor in the University of Connecticut Administrator Preparation Program, a longtime champion of the Schoolwide Enrichment Model, and as an organizer for Neag School leadership conferences.

Outstanding Higher Education Professional

Sylvester Kent Butler Jr. ’85 (CLAS), ’94 MA, ’99 Ph.D.

A professor of counselor education and school psychology at the University of Central Florida (UCF), Sylvester Kent Butler Jr. has been serving in higher education for more than two decades. A three-time UConn graduate, with two advanced degrees from the Neag School, Butler is now also part of the UCF president’s cabinet, overseeing the Office of Diversity and Inclusion as interim chief equity, inclusion, and diversity officer. His research — spanning such areas as African American student achievement and success as well as multicultural and social justice issues in counseling — has been widely presented and published in books and journals at the national and international levels. Among his many accolades, Butler has been recognized by UCF as a Faculty Fellow for Inclusive Excellence, received the Tennessee Association for Multicultural Counseling and Development Appreciation Award, and named an American Counseling Association Fellow. Known as an accessible and engaged faculty member, he also has demonstrated his leadership in two large counseling professional organizations, including the Association for Multicultural Counseling and Development, for which he has served as president. His most proud leadership role includes being elected the 70th president, and second-ever African American male to serve, of the American Counseling Association.

Outstanding Professional

Melissa Thom ’15 MA

A graduate of the Neag School’s talent development and gifted and talented education master’s program, Melissa Thom serves as a library media specialist for Bristow Middle School in West Hartford, Connecticut. In that role, she is known for her passion for enriching the educational lives of students and teachers. She has been recognized with multiple teacher of the year awards, including a National Council for Geographic Education Distinguished K-12 Teacher Award. Thom’s leadership efforts include serving as the vice president of the Connecticut Association of School Librarians (CASL). With CASL, she recently organized a virtual conference with 150 authors and 500 attendees. An accomplished presenter, Thom has spoken to local, national, and international audiences. During the pandemic, she has used her extensive social media presence, including her nearly 4,000 followers, to support and engage with other educators.

Distinguished Alumna

Jamelle Elliott ’96 (BUS), ’97 MA

A standout student-athlete and member of UConn’s first NCAA Championship team, Jamelle Elliott is in her second stint as an assistant coach for the UConn women’s basketball team entering the 2020-21 season. A two-time UConn graduate, including an advanced degree in sport management, Elliott was previously on the UConn Athletics staff from 1998 to 2009, helping guide the UConn Huskies to five national championships. Elliott went on to serve as the head women’s basketball coach at Cincinnati from 2009 to 2018. The Bearcats earned two postseason berths, and every student-athlete who exhausted their eligibility earned their degree. After Cincinnati, Elliott returned to UConn to serve as the associate athletic director for the National C Club, before being named assistant coach. The National C Club connects alumni athletes with one another, as well as with UConn’s current student-athletes, through mentorship, networking, and internship opportunities. She implemented the Positive Performance Mental Training Academy for student-athletes during her tenure and also spearheaded a student-athlete leadership development program. Elliott is known among the coaching staff and players as a great teacher, communicator, and recruiter.

The 23rd Annual Neag School Alumni Awards Celebration begins virtually at 5:30 p.m. on March 13, 2021. Join us for the celebration by registering online at s.uconn.edu/NeagAlumni2021. Questions? Contact neag-communications@uconn.edu.