District Administration (Neag School’s Suzanne Wilson is featured about effective teacher professional development)

High School Students are Showing Increased Interest in Politics, Human Rights, Activism

The Daily Campus (Neag School’s Glenn Mitoma and Neag alum Jake Skrzypiec are quoted about survey on high school student activism)

Editorial: U.S. News Rankings Showcase the Quality of Neag

Daily Campus (Neag School’s recent rankings are featured in an editorial)

Alma Exley Scholars Share Experience at UConn

Alma Exley (Alumni Justis Lopez and Orlando Valentin featured at Annual L.I.D. Conference)

Income, Race Big Factors in Rates of Gifted Students Across U.S.

Columbus Dispatch (Del Siegle interviewed about recent research on the impact of poverty on the identification of gifted low-income students)

A More Accessible ACT and SAT

National Review (Research on required/free tests by Neag School’s Joshua Hyman is mentioned)

UConn’s Jim Penders Gets 500th Win

Hartford Courant (Neag School alumnus achieves his 500th win as UConn baseball coach)

Neag School Honors Seven Outstanding Alumni at Annual Celebration

This past Saint Patrick’s Day, members of the Neag School of Education Alumni Board; Neag School faculty, staff, and administrators; friends of the University; and families gathered around tables draped in purple in the Rome Ballroom of the University of Connecticut’s Storrs campus to celebrate the achievements of seven Neag School alumni during the 20th annual Neag School of Education Alumni Awards Celebration.

“Tonight, we are celebrating this event for the 20th consecutive year. That is a milestone we are very proud to be commemorating here in the Neag School,” said Dean Gladis Kersaint, after welcoming event attendees.

In addition to honoring award recipients, the Alumni Board recognized recipients of the Neag School Alumni Board Scholarship, Dionna Denée Jackson and Elena Sada. The $1,000 award, established three years ago, is granted to Neag School students to help support them through their pursuits in higher education. Jackson is currently enrolled the Neag School’s Higher Education and Student Affairs master’s program, and Sada is a Ph.D. candidate in the Neag School’s curriculum and instruction program.

The Alumni Board also formally recognized the recipient of the inaugural Dr. Perry A. Zirkel Distinguished Teaching Award, which honors a faculty member in the Neag School for excellence in teaching, and the 2018 Rogers Educational Innovation Fund Award, a $5,000 award bestowed upon a Connecticut educator at the elementary or middle school level for innovative and collaborative work in the classroom.

D. Betsy McCoach, a professor in the measurement, evaluation and assessment program, which is directed toward individuals interested in learning more about student assessment and evaluation techniques in formal and informal education settings, received the Dr. Perry A. Zirkel Distinguished Teaching Award. McCoach received her Ph. D. in educational psychology, a 6th Year certificate in school psychology, and masters of arts in education from the University of Connecticut.

Dwight Sharpe, an eighth-grade mathematics teacher at Woodrow Wilson Middle School in Middletown, Conn., received the Rogers Award for his work using robotics and computer programming to engage students in mathematics and engineering.

The award “is really more amazing for my students — to be able to expose them to robotics and an understanding of science and mathematics. It really does open up a lot of opportunities for them that they might not otherwise be able to have in our typical public school setting,” said Sharpe after the event.

After a three-course dinner, the alumni awardees were recognized for their accomplishments in the field of education:

Outstanding Early Career Professional

Xaimara Coss ’04 (ED), ’16 MS — Licensing manager for the National Basketball Association

Xaimara Coss is a two-time graduate of the Neag School of Education, receiving her bachelor of science in sport management in 2003, and her master of science in sport management in 2016. During her undergraduate career, she was a student-athlete, playing for UConn women’s volleyball.

Coss is currently in her sixth year at the NBA and has travelled nationally and internationally as an ambassador for the WNBA’s “Watch Me Work” initiative, where she travelled to Chile and Argentina to share her experiences working in sports. She also serves as a mentor to help new employees become orientated and familiar with the NBA’s best practices.

“My passion started off when I was a young kid; I was always intrigued with what were people doing on the court, around the arena, and how they get people together. Then my passion for giving back started when I played volleyball in high school. My high school coach taught me that giving back was so important,” says Coss.

Outstanding School Educator

Jennifer Lanese ’94 (ED), ’95 MA — English teacher at William H. Hall High School in West Hartford, Conn.

Jennifer Lanese is in her 17th year as an English teacher, and earned her bachelor of science in secondary education and master of art in education, both from the Neag School in 1994 and 1995, respectively. She teaches British literature and serves as the advisor of Hall High School’s Action Club, which strives to promote social justice and equality. In 2015, she was recognized as West Hartford’s Teacher of the Year for her work.

“There’s a saying that meaningful work gives reason to existence, and I am so lucky and grateful to have found one of those reasons working as a public high school English teacher,” says Lanese. “Every day I get to interact with funny, bright, inspiring young people, and get to work with bright, creative, funny, inspiring colleagues. Every day I get to learn something new.”

Outstanding School Administrator

Samuel Galloway ’01 6th Year — Director of Human Resources at Bristol Public Schools

Samuel Galloway began his work as the director of human resources at Bristol (Conn.) Public Schools in 2014, after serving as principal of Bloomfield High School. While at Bristol Public Schools, he has increased school administrator and faculty diversity and has worked with two high schools to increase graduation rates.

Prior to his work in education, he was a trooper for the Connecticut State Police and corrections officer and served as a First Lieutenant in the U.S. Army. He received his 6th Year teaching certification from the Neag School in 2001, and received his Ph. D. and superintendent certificate from Central Connecticut State University.

“I’m blessed that I had the opportunity to operate in capacities where either I protected or I served, and that has been a blessing. I thank you for the honor, and I am very proud to have gone to UConn,” says Galloway.

Outstanding School Superintendent

Nathan D. Quesnel ’01 (ED), ’02 MA — Superintendent of East Hartford Public Schools

Nathan D. Quesnel has served as the superintendent of East Hartford (Conn.) Public Schools for the past five years, and has worked to address challenges associated with urban districts, as well as with community organizations to overcome funding challenges and build partnerships with outside organizations, such as Pratt and Whitney, to ensure students have the opportunity to apply their skills. He also has created programs to increase reading scores by 50 percent and math scores by 61 percent on Renaissance Learning’s STAR Reading and Math assessments, and lowered in-school suspension rates by 44 percent.

“I really appreciate the UConn Alumni Board and UConn as a whole. I had no interest in going to college. I wanted to be a carpenter, a ski bum, or a paratrooper. My father said to try school for a year. I’m really glad, Dad, [that] you pushed me there,” says Quesnel.

Outstanding Professional

Carol D. Birks ’08 ELP — Superintendent of New Haven Public Schools

Carol D. Birks was the former chief of staff at Hartford (Conn.) Public Schools (HPS), and now serves as the superintendent at New Haven Public Schools. Birks earned her superintendent preparation certification from the Neag School in 2008. As HPS’ former chief of staff, Birks oversaw administrative day-to-day management and operations. She also spearheaded the district’s redesign and restructure initiative in order to improve student outcomes.

As superintendent of New Haven Schools, she wants to push for systematic change within the district, ensure community healing, and create a vision where students are reading at or above grade level and have pathways to pursue postsecondary education.

“I want thank the many educators and my family for pushing my thinking and helping me to reflect and learn. I committed my life to supporting young people who have faced many obstacles so they can reach their full potential. The foundation of education I received here at UConn was exceptional, so I am truly grateful (to be recognized),” says Birks.

Outstanding Higher Education Professional

Mohammad Zaheer ’74 Ph.D. — Professor of Economics, retired, Manchester Community College

Mohammad Zaheer is a retired professor of economics at Manchester Community College (MCC) who taught for 20 years, as well as at Eastern Connecticut State University, Albertus Magnus College, and Southern Connecticut State University. At MCC, Zaheer served as the department chair and on several committees.

He received his Ph.D. in business education from the Neag School in 1974. In addition to his teaching positions in Connecticut, Zaheer taught at the Government College of Science in Pakistan and U.S. International University in Kenya. He has published a number of books and research publications on the field of economics and teaching, and still continues to contribute to the field.

“There is no other profession worth pursuing than teaching,” says Zaheer.

Distinguished Alumna Award

Persis Rickes ’80 (CLAS), ’81 MA, ’93 Ph.D. — president and principal of Rickes Associates, Attleboro, Mass.

Persis Rickes is the principal and president of Rickes Associates, a higher education planning firm, founded in 1991, that specializes in space utilization, space programming, and strategic planning for colleges and universities. Rickes Associates has served more than 200 institutions on nearly 400 projects in 25 states and internationally.

Prior to establishing her firm, Rickes served as UConn’s director of planning, developing the university’s master plan. While an undergraduate student at UConn, she wanted a better understanding of how people came together to create the university experience, so she spoke to University administrators to understand how all the pieces fit together.

She earned her bachelor of arts in psychology from the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences in 1980, master of arts in higher education administration in 1981, and Ph. D. in professional higher education administration, all from UConn.

“It’s incredibly humbling to have recognition from the Neag School after all the years, and it has reminded me of how strong of a connection I did have when I was a student here,” says Rickes.

Check out additional photos from the 20th annual Neag School Alumni Awards Celebration. Access the full playlist of all seven videos featuring Neag School 2018 alumni awardees on the Neag School YouTube channel.

All videos produced by Ryan Glista.

Related Stories:

10 Questions With Counseling Professor Clewiston D. Challenger

In our recurring 10 Questions series, the Neag School catches up with students, alumni, faculty, and others throughout the year to offer a glimpse into their Neag School experience and their current career, research, or community activities.

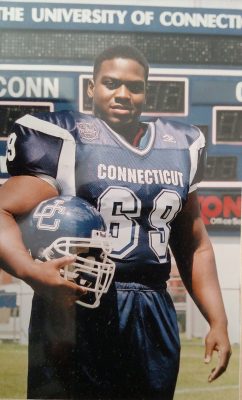

Clewiston D. Challenger joined the Neag School as an assistant professor of counseling last year. In 2003, Challenger earned his undergraduate degree in psychology and minor in criminal justice from UConn’s College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, and played football for UConn as a walk-on. He earned a master of arts in educational psychology from the Neag School’s counseling program in 2008, and a Ph.D. in counselor education and supervision from Pennsylvania State University in 2017.

Challenger’s research focuses on self-efficacy, academic motivation, and adjustment of students of color at predominately white institutions. He is a nationally certified counselor by the National Board of Certified Counselors, and has experience working as a school counselor in middle schools in New York City and Hartford, Conn., and at Penn State’s Morgan Academic Support Center for Student-Athletes.

What was your experience like as a student-athlete during your undergraduate career at the University of Connecticut, and how did it influence your graduate career and inspire you to pursue your current career? It was special to me in the sense that I had the ability to be in both worlds, both as a student and an athlete. I wasn’t recruited to play at UConn; I came as a walk-on, and that allowed me to have an experience at UConn that was pretty special because I was able to bridge both worlds. I always reflect on what got me to college, what got me to UConn, who helped me along the way, and who opened doors for me — and sports was one of them, school counselors were another, and so was the community I grew up in. I asked that same question of myself when I was a professional school counselor: If I were to go back to school, what would I go to grad school for? And I said school counseling, because I thought about all of the things that made me successful: School counselors always guided my way. I decided I wanted to train counselors to be good school counselors. I also wanted to train counselors to be good urban school counselors, particularly people who are not of color to be effective, multicultural counselors.

“I always reflect on what got me to college, what got me to UConn, who helped me along the way, and who opened doors for me — and sports was one of them, school counselors were another, and so was the community I grew up in.”

— Clewiston D. Challenger ’03 (CLAS), ’08 MA, assistant professsor

What made you want to come back and teach at UConn and the Neag School of Education? What makes these programs special, and what do you hope to contribute? UConn is a large university that is fully resourced. UConn has always led with technological advancements, has always led with campus development, and these things are important because you can be more effective in the work that you want to do when the institution is well resourced. When schools have more resources, they get more done. I recognized that I could get more done being at a place like UConn that has more resources.

What are your roles at UConn? I teach four classes in the counseling department at UConn. We’re a school counseling program that focuses on social justice, urban school counseling, and underrepresented populations in low-resourced schools.

What is it like being on the other end of the spectrum, teaching and conducting research at the institution where you started your career? It’s very much a shift because now I am literally looking in the looking glass, back at my own experience. When I was a student, I didn’t notice being a black male student-athlete, how that impacted my experience on campus. It’s odd now to be back at UConn as a faculty member because it’s come full circle. I came back to the college I went to, but I’m also a faculty member for the program that trained me, so it’s like coming back home to the place I first started on this journey and now I get to pay homage to that. At the same time, I’m also getting to pay it forward to the students I’m training, to the student-athletes I’m studying, and to the doctoral students that I’m able to influence. I really love and appreciate the role I have now, and also am very grateful and very proud of being a Husky.

What is the scope of your research? I research self-efficacy, how someone perceives their ability to do a task; academic resiliency, which is how students handle academic setbacks; and I look at university attachment and how all those factors influence academic motivation. If you’re well-adjusted to school, you have a higher chance of doing well. I also look at students of color, and particularly student-athletes of color who attend predominantly white institutions, like UConn and Penn State, because their experiences are different. They’re usually high-profile athletes brought in to play a sport and win games, but often the school climate and demographic makeup generally doesn’t look like the student, nor does it reflect their cultural or ethnic values. What I’ve found in my research is that those factors tends to impact their college experience, their adjustment to the school, and also impacts their academic performance.

You’ve worked at urban and suburban schools. What do you see as some of the biggest differences in school needs between rural, urban and suburban areas? The resource and social capital gap between urban and rural is actually closing, because those needs are becoming equally as high. Deep rural areas have high poverty rates and low-resourced schools as well. The same could be said for urban areas, where there are lower resources but are more densely populated. They’re fairly similar, but urban and rural are vastly different in culture, demographic makeup, and even family makeup. The one that stands out as most distinct is suburban because [those schools] typically have all the resources they need for students to be academically successful.

How did your experiences working at urban schools compare to working at suburban schools? I worked in New York City as a middle school counselor, where we had a club track team. Our students would literally run around the block [instead of at a track]. [But starting] the team — that little thing changed the attitudes of the students. The school really appreciated those kinds of gestures that teachers and educators were bringing in. I’ve worked at suburban schools where they already have the resources, so it wouldn’t be as appreciated if you started a track team; it kind of would just be expected.

From your perspective, how do the educational needs between boys differ from the needs of girls? How can educators meet different needs to create a positive impact on students? In my experience, boys have tangible learning experiences; basically, when they have to complete tasks for their learning, they tend to thrive. They’re able to exert that energy to the task and complete a project. To most boys, that really meshes with their personalities. The traditional educational model we have today works better for girls. That’s why teachers and counselors have to cater how they teach their classes and counsel boys and girls, because you have to differentiate the work in order to get comparable results.

Some of your research focuses on school engagement of boys in urban areas, and as a school counselor in New York City schools, you established intervention programs for at-risk students. What made you want to focus on boys in urban areas? I wanted to be able to create systemic change that wouldn’t just impact one school or one district. I wanted to create policy or academic work that would be effective across the U.S. or the world, and I knew I couldn’t do that from the office of one school. I wanted to know why students of color were struggling in schools, and were they able to do better. There’s a list of things that box people in, but I wanted to focus on education because you can unbox yourself if you know more. I decided I wanted to be in urban education because of the challenge. These schools and communities have the most need, and if anything, you see the most change in a short period of time from your interventions.

What do you try to instill in your students, and what do you hope they learn from you? I hope they learn to understand the different angles and perspectives of others, and the reason that’s important is that when you work with human beings in general, everyone has a different story. And, everyone’s looking at the same book differently. Students who desire to be school counselors have to realize that the students and families they serve are not all looking from their perspective, so the one thing I want to teach my students is their lens is not the most important lens. I encourage them to develop a kaleidoscope lens to view through and to learn to keep turning to see how things look differently from others’ perspectives. That’s important because salient to each of us as individuals are our own stories; we tend to put our backgrounds and our beliefs ahead of everything.

Connecticut’s 2018 Letters About Literature Contest Winners Named

The Neag School of Education, the UConn Department of English, and the Connecticut Writing Project (CWP) at UConn are proud to announce Connecticut’s winners of the 25th annual Letters About Literature competition, a nationwide contest sponsored by the Library of Congress for students in grades 4 through 12.

This fall, the Neag School, the Department of English, and the CWP served as the contest’s Connecticut sponsors for the 2017-18 academic year; Neag Professor Doug Kaufman, CWP Director Jason Courtmanche, and Neag School Ph.D. candidate Dani King-Watkins served as the contest’s representatives for the state of Connecticut.

This fall, the Neag School, the Department of English, and the CWP served as the contest’s Connecticut sponsors for the 2017-18 academic year; Neag Professor Doug Kaufman, CWP Director Jason Courtmanche, and Neag School Ph.D. candidate Dani King-Watkins served as the contest’s representatives for the state of Connecticut.

There were more than 1,300 submissions from Connecticut students, and 120 finalists. Each finalist will receive a certificate of recognition. Nine winners from each of the contest’s three categories (Grades 4-6, Grades 7-8, and Grades 9-12) have been selected, and each will receive a cash prize and state recognition, which includes a special ceremony at the Connecticut State Capitol Building on Friday, April 20. From those nine winners, three first-place winners have been selected, who will now advance to the national competition, for which winners will be chosen later this month. Read more about the contest here, and click the students’ names below to read their winning essays.

Congratulations to the winners for the state of Connecticut:

Level I (Grades 4-6)

- First place: Dominic Roussos, King Philip Middle School, West Hartford (Teacher – Lucinda Kulvinskas) — Essay based on The King’s Stilts by Doctor Seuss

- Second place: Jackson Drew, Macdonough School, Middletown (Teacher – John Ferrero) — Essay based on Wonder by R.J. Palacio

- Second place: Clare Sweeney, King Philip Middle School, West Hartford (Teacher – Lucinda Kulvinskas) — Essay based on Out of My Mind by Sharon Draper

Level II (Grades 7-8)

- First place: Katherine Van Tassel, Worthington Hooker School, New Haven (Teacher – Eden Stein*) — Essay based on The Book Thief by Markus Zusak

- Second place: Michelle Zhu, Mansfield Middle School, Storrs (Teacher – Melissa Szych) — Essay based on The Crystal Ribbon by Celeste Lim

Level III (Grades 9-12)

- First place: Brielle Cayer, Middletown High School, Middletown (Teacher – David Frankel) — Essay based on Just Listen by Sarah Dessen

- Second place: Keely Barletta, ACES Educational Center for the Arts, New Haven (Teacher – Deborah Cannarella) — Essay based on We’ll Paint the Octopus Red by Stephanie Stuve-Bodeen

- Second place: Allison Blume, Rockville High School, Vernon (Teacher – Shaune Santos**) — Essay based on Mr. Terupt by Rob Buyea

- Second place: Minahil Farooqi, Edwin O. Smith High School, Storrs (Teacher – Amy Nocton* **) — Essay based on I Am Malala by Malala Yousafzai

* Affiliated with CWP

** UConn alumna/us

Thank you again to the Neag School’s and CWP’s contest judges, who are current students in either the Neag School of Education Integrated Bachelor’s/Master’s program or in the Department of English:

Rhianna Bennett

Andrea Cuadrado

Peter Dovidaitis

Nicole Gerardin

Katie Grant

Amethyst Hamby

Sarah Hoag

Tommy Jacobsen

Shane Luery

Marisa Macek

Megan O’Connor

Shelby Phipps

Jill Power

Sadie Robinson

Rachel Ruiz

Gabby Strain

Clarissa Tan

Emily Turin

Samantha White

Kim Yrayta

Check out photos from the Letters About Literature judging day.